July 22, 2015, Modified July 28 and July 31, 2015

Within the affluent democracy, the affluent discussion prevails, and within the established framework, it is tolerant to a large extent. All points of view can be heard: the Communist and the Fascist, the Left and the Right, the white and the Negro, the crusaders for armament and for disarmament. Moreover, in endlessly dragging debates over the media, the stupid opinion is treated with the same respect as the intelligent one, the misinformed may talk as long as the informed, and propaganda rides along with education, truth with falsehood. This pure toleration of sense and nonsense is justified by the democratic argument that nobody, neither group nor individual, is in possession of the truth and capable of defining what is right and wrong, good and bad. Therefore, all contesting opinions must be submitted to ‘the people’ for its deliberation and choice. But…the democratic argument implies a necessary condition, namely, that the people must be capable of deliberating and choosing on the basis of knowledge, that they must have access to authentic information, and that, on this basis, their evaluation must be the result of autonomous thought.

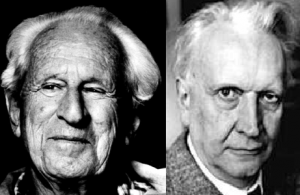

Herbert Marcuse, “Repressive Tolerance,” 1965.

Background: From Herbert Marcuse to Karl Jaspers

Background: From Herbert Marcuse to Karl Jaspers

On June 19, 2015 David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker, wrote a short essay called, “Charleston and the Age of Obama.” Towards the end of his essay, Remnick wrote, “this has been the Age of Obama, but we have learned over and over that this has hardly meant the end of racism in America. Not remotely. Dylann Roof, tragically, seems to be yet another terrible reminder of that.” Remnick is not incorrect about his generally observations, it’s just that his essay falls flat. So too does President Obama’s speech and even Jon Stewart’s impassioned plea for sanity and his matching sense of despair.

Remnick suggests that even Obama can’t raise to the occasion because of a do-nothing Congress. Deconstructing this event as racist or terrorist is often taken to be the beginning, middle and end of the story. In contrast, we could be doing far more with power that is within our grasp. As can be seen in the photo above, across the street from the new New Yorker office at 1 World Trade Center in Manhattan, is 200 West Street, home of Goldman Sachs. It turns out that this financial giant is complicit in the division of labor between racists and rifles. Even academic leaders of liberal universities like Barnard and the New School in New York City have corporate connections to companies backing NRA politicians with extremely low civil rights ratings. The repressive tolerance which makes all opinions acceptable, without a vertical hierarchy attached to them, has led us to a state in which tragedies can unfold within the Thatcherite TINA (“there is no alternative”) framework. Yet, this essay will clearly show that there are alternatives, alternatives which rest on redesigning social movements’ engagements. If one looks for alternatives, one must therefore broaden one’s understanding of who is responsible.

The larger social architecture defined by the academic, political and corporate ties of the gun lobby helps explain how we could systematically take the fight to the NRA and its supporting power structure as well as the moral complacency that helps sustain that power system. In order to understand these linkages, we need to trace through several key steps related to the moral and political economy of assassination in the United States.

The appropriate response to the problematic identified by Marcuse, repressive tolerance, is a broader understanding of guilt and responsibility. Most persons look at Dylann Roof’s actions and see merely moral guilt. Yet, Karl Jaspers in his book, The Question of German Guilt, about German responsibilities in the wake of the Nazi horrors helps us see how more than Roof’s individual actions are involved. Steven Alan Samson at Liberty University nicely illustrates what’s at stake in his short essay on Jasper’s book. In criminal guilt, Jasper identifies persons violating “unequivocal laws,” with jurisdiction resting in the court. Yet, in contrast, political guilt “involves the deeds of statement and implications the citizens of a state” for (in Jasper’s words) “having to bear the consequences of the deeds of the state whose power governs [them] and under whose order [they] live.” In moral guilt, the individual becomes responsible for their actions, and “jurisdiction rests with my conscience.” But with metaphysical guilt, Jaspers writes: “There exists a solidarity among men as humans that makes each coresponsible for every wrong and every injustice in the world…especially for crimes committed in his presence or with his knowledge. If I fail whatever I can do to prevent them, I too am guilty.” Liberal to mainstream society has a very narrow conception of responsibility. Even those who acknowledge the NRA’s complicity rarely dig deeper, to ask who is responsible for and has relations with the very actors supporting the NRA. This detailed chain of causation is tied to not just criminal and moral guilt, but also to political and metaphysical guilt.

Step 1: The Assassination Network I: Racist Culture and its Champions

Step 1: The Assassination Network I: Racist Culture and its Champions

The users of guns in mass killings can be classified as mentally unstable, racists, or terrorists, but to a certain extent the immediate circle surrounding these persons as well as aspects of a larger culture can be said to be supportive or triggering structures for their actions. In any region there can be local racist subcultures, even in areas in which civic leaders try to reverse the institutional support system of racism.

An academic study by Mark R. Leary and his colleagues in the journal Aggressive Behavior in 2003, “Teasing, Rejection, and Violence: Case Studies of the School Shootings” examined fifteen school shootings that took place between 1995 and 2001. They found that “acute or chronic rejection—in the form of ostracism, bullying, and/or romantic rejection—was present in all but two of the incidents. In addition, the shooters tended to be characterized by one or more of three other risk factors—an interest in firearms or bombs, a fascination with death or Satanism, or psychological problems.” Another study in 2000 by Stephanie Verlinden and her colleagues in Clinical Psychology Review, “Risk factors in school shootings,” examined a host of factors contributing to risk factors for youth violence associated with school shootings. These factors include societal and environmental factors including poverty, neighborhood disorganization, media violence, and cultural norms. In sum, these two studies indicated a supporting culture that facilitated violence. This culture is also connected to a political and economic underinvestment in mental health as Mark Follman argues in Mother Jones.

By the same token, the State of South Carolina has ranked high among states as being relatively racist. Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, in his dissertation, “Essays Using Google Data,” published in the Department of Economics at Harvard University, has promoted the use of web searches to help plot the geography of racism. In his study, he identified two racially charged search terms, from January 2004 to December 2007, using the words “nigger” or “niggers.” These terms had different frequency ratings by state. The top ranked state, West Virginia had a rate of 100, followed by Louisiana, Pennsylvania, Mississippi, and Kentucky, with South Carolina ranked relatively high in eighth place, with a rate of 76. Using a Google Trends search of these two terms on June 22, 2015, I found Mississippi ranked 1st with a rate of 100, Louisiana and Kentucky ranked second with a rate of 99, with South Carolina having a relatively high rate of 84, in contrast to the lowest ranked states of Utah (rate 38), Oregon (rate 40) and Hawaii (rate 43). On April 14 2014, Laura Dimon, published data complied by the Southern Poverty Law Center giving “The Complete List of American Cities Where the KKK Is Known To Operate,” listing 110 towns and cities. Two of these were located in South Carolina, Spartanburg and Abbeville.

Further evidence about the racist subculture in South Carolina appears in a recent review by James Yeh. Yeh grew up in South Carolina and is cultural editor at Vice. He points to a continuing acceptance of the legacy of slavery and racism: “From the practice of enslaving African workers on rice plantations to lynch mobs led by Benjamin Tillman, a former state governor and US senator, these kinds of actions are inseparable from the cultural fabric here. Even at the statehouse today, there is a statue honouring ‘Pitchfork Ben’ and his name adorns the most prominent building at Clemson University, the state’s top-ranked public university.” Yeh, continues: “the history of racist violence includes the tale of former Confederate-scout-turned-postbellum-tax-evader Manson ‘Manse’ Jolly. As the story goes, Jolly murdered a host of freedmen Federal soldiers, dumping some of their bodies in a well in Anderson County, where there is a road named after him…in a 2009 article published by the Independent-Mail, he’s hailed as ‘legendary’ twice in the first couple paragraphs, a ‘Civil War hero’ in one breath and an ‘unreconstructed Rebel’ in the next.” There are limits, however, to the depiction of South Carolina as being soft on racism, because certain exemplary efforts have been made to turn the tide. A study by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2011 found that South Carolina earned a B grade based on the coverage given to the civil rights movement and curriculum frameworks, putting it in the top six out of fifty-one regions studied (all fifty states plus the District of Columbia).

In sum, there are regions which condone symbolic violence and these are tied to local subcultures supportive of racism. Yet, we also need to think about how technologies can empower the most extreme racists and how to problematize the links between racists and rifles.

Step 2: The Technology Artefact I: Guns as Self-Defense

Step 2: The Technology Artefact I: Guns as Self-Defense

Are guns tools of self-defense, mechanisms of racism violence or both? Guns should not be considered as mechanisms of power or self-defense without considering the relations in which they are embedded. Guns are artefacts potentially tied to a regulatory system designed and enforced by the state, which in turn is affected by corporations. The ability of a group to use or not use weapons for self-defense and the decisions of the state to promote guns, the right to self-defense and the victims of gun use vary over time and by social group. Research suggests that while gun control has been used to disenfranchise African Americans, gun use has had limits in its ability to defend African Americans. Guns controlled by the state have been used to repress African Americans as well. Yet, the debate about gun use and control often sidesteps a discussion of the countervailing power systems that can place limits on gun violence, political repression or the underdevelopment tied to the culture of violence.

In 1991, Stefan B. Tahmassebi, then Assisant General Counsel of the National Rifle Association, published a study called “Gun Control and Racism.” Tahmassebi wrote that: “the first gun control laws were enacted in the antebellum South forbidding blacks, whether free or slave, to possess arms, in order to maintain blacks in their servile status.” After the Civil War, governments in the South “continued to pass restrictive firearms laws in order to deprive the newly freed blacks from exercising their rights of citizenship.” He adds that “firearms ownership restrictions were adopted in order to repress the incipient black civil rights movement.”

Tahmassebi shows how guns served as a means for self-defense. During the latter part of the 17th Century, a fear of slave revolts in the South sped up the passage of laws which addressed African Americans’ ownership of firearms. For example, Virginia passed “An Act for Preventing Negroes Insurrections.” In the Dred Scott case of 1857 which held that neither freed nor enslaved African Americans could be citizens, Chief Justice Taney argued that making African Americans citizens “would give them the full liberty of speech in public and in private upon all subjects which its own citizens might speak; to hold public meetings upon political affairs, and to keep and carry arms wherever they went.” By 1868, Representative Benjamin F. Butler (R., Massachusetts), argued that the right to keep arms was needed to protect “not only against the state militia but also against local law enforcement agencies.” Butler pointed to cases where “armed confederates” terrorized the African American and “in many counties they have preceded their outrages against him, in violation of his right as a citizen to ‘keep and bear arms’ which the Constitution expressly says shall never be infringed.”

When Congress considered legislation to suppress the Ku Klux Klan in 1871, it originally had a provision when introduced to the House Judiciary Committee making persons guilty of larceny if they took away or deprived any citizen of the United States any weapons or arms they had for protection, “without due process of law, by violence, intimidation, or threats.” Butler explained that “there were very many instances in the South where the sheriff of the country had preceded [the midnight marauders attacking peaceful citizens] and taken away the arms of their victims.” In Union County, the African American population “were disarmed by the sheriff only a few months ago,” Butler explained, “under the order of the judge.” After the sheriff disarmed the citizens, “the five hundred masked men rode at night and murdered and otherwise maltreated ten persons who were in jail in that county.”

Therefore, a division of labor between the state and racist extremist organizations inflicted violence on African Americans who had no other apparent means of defense. Yet, Tahmassebi’s argument partially depends on the idea that government authorities will act on behalf of African Americans in order to protect their rights. However, by his own admission the state often does not protect these rights. At one point he writes, poor and minority citizens depend on arms more than affluent citizens who live in “safer and better protected communities.” At the time his study was published, Tahmassebi added that “in many jurisdictions in which police departments have wide discretion in issuing firearm permits, the effect is that permits are rarely issued to poor or minority citizens.” This suggests that one cannot assume that the state will protect African American citizens’ rights as extensively as the rights of others.

If guns are needed as a counterbalance to a coercive state, one must also realize that there may be more significant barriers to a coercive state than guns. One such barrier is a state in which there is a powerful trade union movement. Yet, there is no linkage between having guns and trade union power. The Small Arms Survey of 2007 indicates the number of firearms per 100 people. Two countries with the most handguns per 100 persons were the U.S. (88.8) and Norway (31.3). Yet, unionization rates in 2007 were only 11.6 percent in the U.S., but 53.0 percent in Norway according to OECD statistics. Two countries with fewer handguns per 100 persons were the U.K. (6.2) and Japan (.6), yet unionization rates that year were 27.9 percent in the U.K. and 18.3 percent in Japan. In this group of states, the United States was the country with the most guns and the lowest unionization rate. The country with the second highest gun density (Norway), actually had the highest unionization rate. The country with the lowest gun density (Japan), had unionization rates that were even higher than the United States.

Another limit to Tahmassebi’s argument is to analyze what has happened when African Americans actually use guns on an organized basis for self-defense. The Black Panther Party is a case in point. While advocating “armed self-defense” as a solution to police violence and harassment, violent attacks and provocations aimed at the Panthers led some leaders in that group to abandon its earlier call for “armed insurrection.” In Black Against Empire, Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr. explain that in 1971 “the Party had moved definitively away from advocating insurrection.” One could easily argue that even those advocating peaceful means of protest were assassinated and that possession guns in one’s own home is not the same as a public, collective display of weapons (one of the tactics of the Panthers). Yet, the larger point is the use of weapons for self-defense can easily trigger police violence, leading to other tactics to promote security, i.e. “alternative security measures.” For example, when the Black Panthers abandoned the call for armed insurrection, Bloom and Martin explain that they “sought to build power through other means.” These included not only a service program, but also (in the case of the Oakland Panthers) “an extended boycott of Bill Boyette, a local black businessman who owned markets in black neighborhoods and ran a black business association…but refused to donate to the Black Panther Party.” This pressure led to an agreement in which Boyette’s stores “would now donate regularly to the Party’s programs, and the Party would call off the boycott.” Another alternative line of action was the development of deeper relations with African American elected officials, like progressive members of Congress Ron Dellums and Shirley Chisholm.

Thus, while gun control can be used by the state to disarm African Americans and their right to self-defense, the mechanisms of self-defense don’t necessarily depend on guns but can be carried out by other means. These other means include mechanisms to challenge the state without necessarily resorting to guns. In fact, when guns have been used collectively to challenge the state, the resulting backlash against this defense has further triggered state violence. In other words, even if gun control were a mechanism to facilitate violence against African Americans, it does not necessarily follow that guns are the necessary or exclusive response to such problems. In any case, one has to consider a larger political formula in which racists’ use of guns reflects not simply racists linked to guns, but also the system a state uses to regulate or limit the use of guns and racist actions. This brings us to the system of state regulation (how well gun use is monitored and which guns are limited) and why such regulation is necessary.

Step 3: The Technology Artefact II: Guns as Tools of Mass Violence

Step 3: The Technology Artefact II: Guns as Tools of Mass Violence

The ways in which guns are deployed has something to do with the systems in which they are embedded. Given the extensive scope of certain racist organizations or a larger racist culture, guns take on a new meaning as potential tools of such organizations. In his book, Lethal Arrogance: Human Fallibility and Dangerous Technologies, Lloyd J. Dumas explains how dangerous technologies can escape our ability to regulate or control them. We can classify dangerous technologies as those which are “capable of producing massive amounts of death, injury and/or property damage within a short span of time.” The intentional use or accidental use or regulatory failure can create tremendous damage. The idea of “dangerous technologies” is often applied to weapons of mass destruction or nuclear power plants. Yet, serial killings and terrorism afflicting schools, military bases and churches illustrate how hand guns and rifles can spark terror and mass fear. An article by Mark Follman, Ted Miller and colleagues in Mother Jones in May-June of this year, “What Does Gun Violence Really Cost?,” found a total cost of $229 billion, costing an average of $700 per U.S. citizen per year. The article explains that “each year more than 11,000 people are murdered with a firearm, and more than 20,000 others commit suicide using one. Hundreds of children die annually in gun homicides.”

One reason why many die is linked to the density of gun use. A report in 2007 by the Switzerland-based Small Arms Survey found that even though the United States had less than 5 percent of the world’s population, it had “about 35–50 percent of the world’s civilian-owned guns.” Gun deaths have declined in recent years with 3.6 gun homicides per 100,000 people in 2010, compared with 7.0 in 1993. Yet, another article by Mark Follman in Mother Jones shows: “there appears to be a relationship between the proliferation of firearms and a rise in mass shootings: By our count, there have been two per year on average since 1982. Yet, 25 of the 62 cases we examined have occurred since 2006. In 2012 alone there have been seven mass shootings, and a record number of casualties, with more than 140 people injured and killed.” Thus, while gun homicides have decreased, mass shooting incidents appear to have increased in their frequency and to a certain extent scale from 1982 to 2012.

The basic idea behind lethal arrogance is that those companies putting these dangerous technologies in circulation have a responsibility for their deployment. This responsibility cannot be displaced or weakened by appealing solely to expected regulations, i.e. assumptions that technology will be used safely and responsibly. The reason why we cannot make this assumption is that these technologies have been used to ill effect repeatedly and if the regulatory system fails, then we cannot use the expectation of regulations to rationalize the existence of the technology. In the case of handguns and rifles, we can safely conclude that such technologies are at the very least under-regulated. The theory of lethal arrogance shows why any political party or economic interest backing under-regulation and lethal technologies becomes responsible for the consequences of these technologies.

Gun control is often discussed as a limit to citizens’ use of guns, but not the state’s (potentially repressive) use of guns. In contrast, theories of multi-lateral disarmament suggest that we must also limit the state’s possession and use of weapons. Thinkers like Seymour Melman and Marcus Raskin (among others) have explained that while a country has a right to self-defense, it should also create systems and legal agreements to phase out the use of weapons gradually, involving state action and mass citizen involvement. Thus, even if weapons are necessary for self-defense, their use should be contingent upon a matching regulatory system that can limit their very use. We therefore need to identify barriers to such a regulatory system. This approach to comprehensive disarmament (as opposed to piecemeal arms control) was partially embraced by the administration of John F. Kennedy as seen in the document: Blueprint For the Peace Race.

Gun control is often discussed as a limit to citizens’ use of guns, but not the state’s (potentially repressive) use of guns. In contrast, theories of multi-lateral disarmament suggest that we must also limit the state’s possession and use of weapons. Thinkers like Seymour Melman and Marcus Raskin (among others) have explained that while a country has a right to self-defense, it should also create systems and legal agreements to phase out the use of weapons gradually, involving state action and mass citizen involvement. Thus, even if weapons are necessary for self-defense, their use should be contingent upon a matching regulatory system that can limit their very use. We therefore need to identify barriers to such a regulatory system. This approach to comprehensive disarmament (as opposed to piecemeal arms control) was partially embraced by the administration of John F. Kennedy as seen in the document: Blueprint For the Peace Race.

Step 4: The Assassination Network II: The Gun Lobby and their Patrons

The under-regulation of guns is a conscious political project of the NRA. If the NRA is like other elite organizations it follows a general formula of organizing of being not only tied to political power but also media and economic power. The supporting pillars of this organization involve not simply a grassroots membership base, but also politicians whom the NRA rents via campaign donations as well as corporate sponsors. Political pressure can be placed on the NRA and these politicians by going after: (a) the direct sponsors of the NRA and (b) the corporate sponsors of NRA-politicians. Failing to polarize and defund these corporations makes us complicit in the organized pattern of public assassinations which the NRA’s policies facilitate.

While the right to bear arms is a Constitutional right, the right to be free from racists, mentally handicapped and badly parented junior assassins is also in theory a right. While I agree in part with the argument that “guns don’t kill people, people do,” the problem now is that technology has extended the physical violence capacity of persons who are basically culturally, mentally and/or ethically deficient. These persons are associated with racist thinking and an NRA which cannot even stomach the most basic regulations necessary for supporting our rights to self-defense from guns and gun owners. These organizations and the culture surrounding them are therefore public dangers, nuisances which must be opposed through concerted public action. I am not saying that the NRA is explicitly racist, only that they are a political bloc providing assistance to racists, i.e. a de facto racist assistance industry. The NRA can argue that they cannot control what any gun owner does with their gun. Yet, governments can control the guns the NRA cannot control. The very lack of control over what citizens can do to other citizens is the foundation for having a government which regulates civil society. The sociologist C. Wright Mills refers to the idea of “organized irresponsibility” and the NRA is a primary champion of a lack of responsibility vis-à-vis gun purchase, regulation and use.

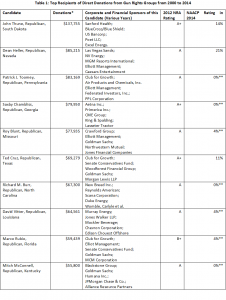

The primary state sponsors of the NRA include a host of Republican politicians. Alan Bekow and Gordon Witkin identified many of these persons in an essay called, “Gun lobby’s money and power still holds sway over Congress,” published on May 1, 2014. The top recipients of direct donations from gun rights groups are listed in Table 1 below, accompanied by additional data I compiled on their corporate sponsors and NAACP civil rights report card ratings. What’s immediately interesting are three facts.

First, leading pro-gun politicians are uniformly also given a low rating on advocacy of civil rights by the NAACP. Racist leaders and weak civil rights support are each associated with the NRA’s top politicians. It cannot simply be a coincidence that Earl Holt III, President of the Council of Conservative Citizens, donated money to Senator Ted Cruz of Texas. The Council is the host of the racist website that inspired Dylann Roof. Thus, while NRA spokesman try to link gun control and racism, NRA backed politicians are themselves relatively weak anti-racists.

First, leading pro-gun politicians are uniformly also given a low rating on advocacy of civil rights by the NAACP. Racist leaders and weak civil rights support are each associated with the NRA’s top politicians. It cannot simply be a coincidence that Earl Holt III, President of the Council of Conservative Citizens, donated money to Senator Ted Cruz of Texas. The Council is the host of the racist website that inspired Dylann Roof. Thus, while NRA spokesman try to link gun control and racism, NRA backed politicians are themselves relatively weak anti-racists.

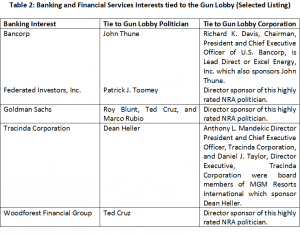

Second, there are a host of companies that assist the NRA agenda by promoting NRA-friendly politicians. These companies are therefore responsible for the actions of these politicians and their role as champions of lethal arrogance and dangerous technologies. These companies include various bankers and financial interests linked to the gun politicians or the companies directly supporting gun politicians. This latter point becomes more apparent in Table 2 below. Jaspers’s larger notions of responsibility certain apply to the corporations and financial elite backing lethal arrogance, dangerous technologies and organized irresponsibility.

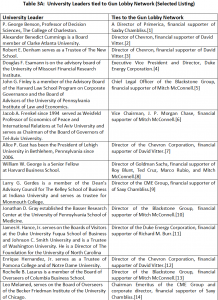

Third, mainstream society, represented for example by non-governmental organizations and universities, are connected to the mainstream corporations which support lethal arrogance. These “civic,” “intellectual” and corporate spaces can become targets of political organizing against the system of lethal arrogance that facilitates racist and other public assassinations. The gap between mainstream societal condemnation of the Charlestown massacre and actual ties to companies backing the gun lobby can be illustrated by several examples.

Richard Williams is a member of the Board of Directors of Primerica, Inc., a supporter of Saxy Chambliss who is a top rated NRA politician. At the same time, Williams serves on the Board of Directors of the Anti-Defamation League Southeast Region. Alison S. Rand, the company’s Chief Financial Officer and a member of the Primerica’s board, is also a board member of the Atlanta Children’s Shelter and the Partnership Against Domestic Violence. One might argue logically that gun control is necessary to reduce domestic violence and that given this connection, Rand should call for Primerica to boycott NRA-backed politicians.

Ms. M. Ann Thomas is the Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of the Woodforest Financial group, Inc., sitting on their Board of Directors. This company was a significant donator to Ted Cruz, a leading NRA politician whose NAACP civil rights record is abysmal (11 percent). Ms. Thomas currently serves as a director of the Human Society of Montgomery County. George Sowers, Jr. is another Woodforest director and executive. Mr. Sowers also serves as a Director of The Woodlands Symphony Orchestra. Carlos A. Saladrigas, is a Director of Duke Energy, the company that backed Richard M. Burr, another gun lobbyist. In 2002, the Miami-Dade Commission on Ethics and Public Trust named him as Top Volunteer Advocate, citing his leadership on ethics and public accountability. One might argue that larger conceptions of humanity, ethics and civilization could act in service of a regulatory system to limit random acts of mass assassination. These connections could be made by pressuring these individuals to drop their corporations’ support for the NRA, champion of lethal arrogance and organized irresponsibility.

Even corporate executives associated with African American organizations or causes in theory aligned with African American interests have been associated with corporations backing gun lobby politicians with extremely low civil rights records. James A. Bennett is a director of the Scana Corporation which financed Richard M. Burr, a politician with an A rating from the NRA who also has had a 0 percent rating from the NAACP. Mr. Bennett was also a recipient of Columbia Urban League’s Board Member of the Year award. Dr. Lee R. Raymond is a board member of J. P. Morgan Chase, a financial backer of Mitch McConnell. McConnell has received a 0 percent rating from the NAACP, but Dr. Raymond serves as a Director of United Negro College Fund, Inc. Carl Ware served as the Principal Architect of Coca-Cola’s 1986 disinvestment from South Africa, yet he is a director of the Chevron Corporation. Chevron gave financial support to David Vitter, who has an A grade from the NRA and a 4 percent NAACP rating. Another Chevron director is Alexander Benedict Cummings Jr., Chief Administrative Office and Executive Vice President of the Coca-Cola Company. Mr. Cummings is a board member of the Africa-America Institute, Africare, and the Corporate Council on Africa. Another director of the United Negro College Fund is James H. Hance, Jr. Mr. Hance sits on the Duke Energy Corporation board, the company backing Richard M. Burr. Burr has received an A rating from the NRA and a 0 percent rating from the NAACP. The communities tied to the Urban League, United Negro College Fund, the history of divestment actions, and the Africa-America Institute should question these individuals about their connections to corporate sponsors of the NRA. This kind of association should certainly be subject to democratic debate, given that risks that NRA policies enhance.

Step 5: Towards a Corporate Campaign

Step 5: Towards a Corporate Campaign

A key tactic which progressive to left communities can use to pressure the liberal and mainstream society to oppose political assassinations is the organization of a public corporate campaign against companies complicit in murder. This campaign would apply counter pressure against the enabling conditions which facilitate: (a) racists and their networks, e.g. racist culture, (b) artefacts embodying lethal arrogance, (c) NRA politicians, and (d) the corporate sponsors of these politicians.

A fitting response to (a) is to target the repressive tolerance of racist regions. This is the great fear that has begun to lead to incremental reform in such regions. With respect to a backlash against the racist symbols of South Carolina, particularly, its prominently displayed civil war icons siding with the Confederacy, a report in The New York Times noted that “many prominent Republicans there are privately hoping the state reaches a consensus…to avert a primary dominated by race related issues, which could turn off the business community and depress the state’s lucrative tourism and convention industry” (see: Jonathan Martin, “Republicans Tread Carefully in Criticism of Confederate Flag,” The New York Times, June 21, 2015). As the Black Panthers earlier established, a boycott can be a central way to leverage power.

One key system vis-à-vis (b) artefacts of violence and lethal arrogance is a system of improved regulation. Yet, such regulation is partially blocked by (c) NRA politicians. If a person, group or organization does not live or is not based in a state where such politicians reside, they nevertheless have indirect leverage over such institutions via (d) the corporate sponsors of the NRA. I have identified these in Tables 1 and 2. The leverage systems against these corporations include: divestment, boycotts of the specific banks or financial institutions, shareholder resolutions and actions to lobby or otherwise influence (e) the university administrators or board members tied to NRA sponsors identified in Table 3A and Table 3B. At the very least, universities tied to the NRA sponsors should explain how Jasperian notions of responsibility somehow fail to implicate their actions.

A campaign directed at the corporations identified in Tables 1 and 2 should call for an end to patronage of the NRA. The individuals identified in Tables 3A and 3B should be lobbied to lobby against their corporation’s support for the NRA.

Yet, as I have shown an earlier essay, the larger power structures supporting racist violence also potentially include police forces. Any movement using these corporate connections to build up networks should also focus on creating alternative banking and cooperative investment alternatives to the financial elites backing the NRA. A positive sign of the potential for such networks can be seen in the JAK bank in Sweden which has 37,000 members and now its own Master Card. Very much like the past boycotts of the Black Panthers, we need to organize public campaigns that contribute to alternative institutions of power. Corporations sponsor politics and politicians that reflect their interests and promote a system of power accumulation to extend these interests. Likewise, we must organize our own corporate and democratic platforms for extending our interests, something described in the New Economy Virtuous Cycle. Our political choices reflect on our capacity to build up an alternative set of economic power accumulators that represent our interests. All politicians should be judged by their capacity to extend such networks. All citizens can be judged by their capacity to respond to repressive tolerance by embracing the largest conceptions of responsibility explained by Karl Jaspers.

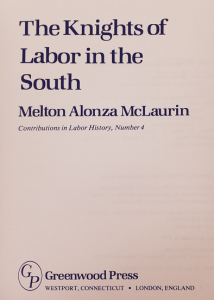

In 1978, Melton Alonza McLaurin wrote the book, The Knights of Labor in the South, published by Greenwood Press. The Knights of Labor were a radical labor movement supporting systematic reforms in support of economic democracy in the United States. This important book explained that “the Knights established strong footholds in every southern state” that was studied “with the exception of South Carolina.” McLaurin shows that the Civil War had “broken the nearly total control” of the Southern economy by the class of planters. Instead, “the new arbiters of South’s economic destiny, though primarily of southern birth, frequently came from mercantile, banking, and industrial backgrounds.” When it came to railroad development, there was a heavy reliance on Northern capital. At the same time, in the late 1800s “domestics and rural day laborers, who were primarily blacks, occupied the bottom rung of the South’s economic latter.” In other words, we see how earlier the banking class came to exercise a key source of influence with respect to Southern political developments in a system in which African Americans occupy marginalized positions. Now as then, Northern bankers occupied key in the circuits of power in Southern development in a system in which African Americans had less economic power.

The Knights of Labor potentially represented a mechanism to challenge this uneven division of political and economic power. McLaurin explains that the Knights of Labor “experimented with both producers’ and consumers’ cooperatives, with limited success.” The also “engaged in bitter, protracted strikes involving laborers in all the region’s major industries as well as many minor ones.” The also “entered the political arena, successfully electing municipal and legislative candidates and members of Congress and obtaining the passage of major reform legislation.” It should be noted, however, that the national order of the Knight “made no serious attempt to instigate a cooperative movement, as did the Farmers’ Alliance.” The Knights also failed to aid “cooperatives established at the local or district assembly level.”

The cooperative program of the Knights “produced only a series of failures,” with the Knights abandoning most cooperative ventures by the end of 1888. Nevertheless, they engaged in a series of very interesting experiments. In Birmingham, Emil Lesser, tried to develop a cooperative town settled by the Knights of Labor. Lesser and other Knights organized a Co-operative Cigar Works which eventually located in Powderly. At one point, the Knights created the T. V. Powderly Cooperative Association which was a general store. In February 1888, Powderly had the cigar works, twenty-six houses, a depot, a post office, a general store, a school, “and a hall for the local assembly, the Girard Assembly. In some small towns in the South, the ideal “was to build a two-story building, use the upper floor as a meeting hall, and establish a cooperative grocery or general store below.”

One constraint on growth of such ventures was a lack of “capital resources and knowledge of the manufacturing process.” Another key problem was that “opponents successfully used the order’s liberal policies against it, while white members failed to overcome their prejudices and unite with black members on economic issues.” In fact, “as racial attitudes hardened in the South, whites began to leave” the Knights of Labor, which “became increasingly the refuge of the most downtrodden blacks—the tenant, the rural day laborer, and the domestic worker.”

In sum, in the history of the South and the Knights of Labor represented by McLaurin’s study we see several lessons highly relevant for today and the themes of this article. First, peak economic organizations in the North projected power in the South via the organization of financial capital. Second, the weakness of those forces which cannot challenge the established organization of economic power, itself a basis for political power. Third, the inter-racial political divisions which constrain the organization of alternative and democratic forms of economic power. Fourth, the potential capacities for organizing an economic alternative by leveraging consumption power, if not production power. Fifth, the weakness of technical capacities tied to an alienation (or separation) from manufacturing. Unfortunately, many discourses about racism, dis-empowerment, police shootings and the like fail to address these fundamental questions. Books like McLaurin’s are simply ignored and are part of the social amnesia process which political critic Rusell Jacoby explains is a key way in which the status quo is maintained. Our very own social movements often further alienate us from these lessons of the past and thus the ability to systematically accumulate power and thereby end the tragedies associated with powerlessness.

The author is part of the Global Teach In network (see: www.globalteachin.com) and can be reached on Twitter @globalteachin. A slightly different version of this article was published in The London Progressive Journal.

References for Table 1

Notes:

*- Alan Berlow and Gordon Witkin explain: “Gun rights figures include contributions made by political action committees that advocate for firearm freedoms, as well as identifiable gun rights group leaders and activists. Totals do not include contributions of $200 or less, which do not have to be reported to the Federal Election Commission.”

**-2011 rating.

Sources: Alan Berlow and Gordon Witkin, “Gun lobby’s money and power still holds sway over Congress,” Center for Public Integrity, Washington, D.C., May 1, 2014, accessible at: http://www.publicintegrity.org/2013/05/01/12591/gun-lobbys-money-and-power-still-holds-sway-over-congress; “Open Secrets,” Center for Responsive Politics, Washington, D.C., accessible at: http://www.opensecrets.org; “How the N.R.A. Rates Lawmakers,” The New York Times, December 19, 2012, accessible at: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2012/12/19/us/politics/nra.html?_r=0; “Vote Smart,” Philipsburg, Montana, accessible at: https://votesmart.org/; NAACP Civil Rights Federal Legislative Report Card, 112th Congress, 2011-2012, accessible at: http://www.naacp.org/preview/pages/report-cards.

References for Table 2

Sources: Alan Berlow and Gordon Witkin, “Gun lobby’s money and power still holds sway over Congress,” Center for Public Integrity, Washington, D.C., May 1, 2014, accessible at: http://www.publicintegrity.org/2013/05/01/12591/gun-lobbys-money-and-power-still-holds-sway-over-congress; US Bancorp website, accessible at: http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=117565&p=irol-govboard; MGM Resorts International, 2014 Annual report, accessible at: http://mgmresorts.investorroom.com/annual-reports.

References for Table 3

1. Investor Relations, Primerica, Inc., accessible at: http://investors.primerica.com/od.aspx?iid=4245322.

2. Alexander Benedict Cummings, Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/people/person.asp?personId=1147153&ticker=KO&previousCapId=98506&previousTitle=CHEVRON%20CORP.

3. Robert E. Denham, Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/private/person.asp?personId=640457&privcapId=1674644&previousCapId=98506&previousTitle=CHEVRON%20CORP.

4. Douglas F. Esamann, Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/people/person.asp?personId=1611268&ticker=DUK&previousCapId=267850&previousTitle=DUKE%20ENERGY%20CORP.

5. Blackstone Group LP, Form 10-K, 2015, accessible at: http://d1lge852tjjqow.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001393818/ee32be8c-1caf-4f70-b92c-6cbb1f104abf.pdf.

6. Jacob A. Frenkel, PhD, Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/people/person.asp?personId=342990&ticker=JPM&previousCapId=658776&previousTitle=JPMORGAN%20CHASE%20%26%20CO.

7. Alice P. Gast, Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/private/person.asp?personId=13482071&privcapId=3749076&previousCapId=98506&previousTitle=CHEVRON%20CORP.

8. Goldman Sachs, 2014 Annual report, 2015, accessible at: http://www.goldmansachs.com/investor-relations/financials/current/annual-reports/2014-annual-report-files/annual-report-2014.pdf.

9. Investor Relations, CME Group, accessible at: http://investor.cmegroup.com/investor-relations/directors.cfm?bioID=16091.

10. Blackstone Group LP, Form 10-K, 2015, accessible at: http://d1lge852tjjqow.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001393818/ee32be8c-1caf-4f70-b92c-6cbb1f104abf.pdf.

11. James H. Hance, Jr., Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/people/person.asp?personId=229436&ticker=FDO&previousCapId=267850&previousTitle=DUKE%20ENERGY%20CORP.

12. Enrique Hernandez, Jr., Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/people/person.asp?personId=608232&ticker=WMIH&previousCapId=98506&previousTitle=CHEVRON%20CORP.

13. Blackstone Group LP, Form 10-K, 2015, accessible at: http://d1lge852tjjqow.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001393818/ee32be8c-1caf-4f70-b92c-6cbb1f104abf.pdf.

14. Investor Relations, CME Group, accessible at: http://investor.cmegroup.com/investor-relations/directors.cfm?bioID=7626.

15. US Bancorp website, accessible at: http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=117565&p=irol-govboard.

16. Investor Relations, CME Group, accessible at http://investor.cmegroup.com/investor-relations/directors.cfm?bioID=7644.

17. Primerica, 10-K report, 2014, accessible at: http://investors.primerica.com/Cache/29020879.PDF?Y=&o=PDF&D=&fid=29020879&T=&osid=9&iid=4245322.

18. Lee R. Raymond, PhD., Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/private/person.asp?personId=406344&privcapId=6441232&previousCapId=658776&previousTitle=JPMORGAN%20CHASE%20&%20CO.

19. Blackstone Group LP, Form 10-K, 2015, accessible at: http://d1lge852tjjqow.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001393818/ee32be8c-1caf-4f70-b92c-6cbb1f104abf.pdf.

20. Goldman Sachs, 2014 Annual report, 2015, accessible at: http://www.goldmansachs.com/investor-relations/financials/current/annual-reports/2014-annual-report-files/annual-report-2014.pdf.

21. Ronald D. Sugar, PhD, Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/private/person.asp?personId=285767&privcapId=107637&previousCapId=98506&previousTitle=CHEVRON%20CORP.

22. Alfred Trujillo, Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/private/person.asp?personId=7538302&privcapId=4508483&previousCapId=188244&previousTitle=SCANA%20CORP.

23. Carl Ware, Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/people/person.asp?personId=526821&ticker=CVX&previousCapId=98506&previousTitle=CHEVRON%20CORP.

24. John S. Watson, Bloomberg Business Executive Profile, 2015, accessible at: http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/people/person.asp?personId=20462172&ticker=CVX.