By Jonathan Michael Feldman, October 9, 2022; Updated October 10, 2022

“The system is bankrupt when $2.3 million a minute are spent on perfecting the machinery of destruction, whilst the means of survival become increasingly scarce…’Security policy’ has led us ino the most dire insecurity the world has ever faced.”

––Petra Kelly, Fighting for Hope, London: Chatto & Windus, The Hogarth Press, 1984: page 12.

“Militarisation in Turkey can be traced both horizontally (across policy spaces) and vertically (multiplication of armed instruments). Horizontal militarisation, the growing reliance on military and militarist language in both domestic and foreign politics, rests on a populist framing of politics as Turkey’s ‘Second Liberation War’ against the Western imperialist elite and their domestic collaborators. At home, it helps Erdoğan consolidate his mass support and deter opposition. While any challenge (from the depreciation of the Turkish lira to women’s rights) has become cast as part of a larger conspiracy, the militarist liberation war rhetoric makes any social or economic problem only secondary to the ‘survival of the nation’ (milletin bekasi).”

––Hakkı Taş “The New Turkey and its Nascent Security Regime,” (GIGA Focus Nahost, 6). Hamburg: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien, Institut für Nahost-Studien, November 2020, page 5.

“Sweden has a long tradition of taking international responsibility and being a democratic voice and force in the world, and the image of Sweden abroad is positive.”

––”Ett svenskt Nato-medlemskap – förändrar det bilden av Sverige?,” Svenska Institutet, June 14, 2022.

ISP Authorizes Weapons to Turkey

Sweden has normalized a Turkish regime which is militaristic, de-democratizing, and involved in systematic repression of Kurds. This essay explains how the latest authorization of weapons sales to this regime by the Swedish government is part of a larger system which has rendered human rights disposable, even if some politicians raise objections and have temporarily attempted to limit support for Turkey.

The Institute for Strategic Products (ISP) provides authorization for Swedish weapons exports. In a September 30, 2022 statement, updated October 3, 2022, the ISP announced authorization of Swedish weapons exports to Turkey. This statement (translated below) read as follows: “Sweden’s application for membership in NATO greatly strengthens the defense and security policy reasons for granting the export of military equipment to other member states, including Turkey. With regard to the changed defense and security policy circumstances, ISP has, after an overall assessment, decided to grant a permit for follow-on deliveries from the Swedish defense industry to Turkey. The permit concerns other military equipment within the categories ML11 (electronic equipment), ML21 (software) and ML22 (technical assistance)….The decision to grant permission for follow-on deliveries to Turkey has been preceded by consultation with the Export Control Council.”

The Normalization of Turkey’s Violence

The ISP decision came about two weeks after the UN reported that Turkey may have committed war crimes in Syria and reports a few months earlier about Turkish attacks on civilians in Iraq. Levent Kennez in an article the Nordic Monitor (September 16, 2022) explains: “the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic…in a report published on September 14” referred “to mortar shells that may have been fired from Turkey and several drone attacks killing civilians at various times in 2022.” Another report in Middle East Eye described a Turkish attack in August 2022 as follows: “At least 15 civilians have been killed, including five children, and 30 others wounded in government shelling that hit a busy market and other civilian buildings in the Turkish-controlled city of Al-Bab in northern Syria.”

During this summer, France 24 reported: “Nine civilians including children were killed in a park in Iraq’s autonomous Kurdistan region Wednesday by artillery fire that Baghdad blamed on neighbouring Turkey, a country engaged in a cross-border offensive.” A Turkish attack on Kurdish Iraq on June 25th was criticized by Human Rights Watch (HRW) on in a July 22 post. Belkis Wille at HRW stated that “the Turkish military strike on opposition fighters in a resort area seriously injured several civilians and could have harmed many more.”

In 2018, the BBC reported on earlier Turkish attacks in Syria, based on various sources: “According to the Kurdish Red Crescent, attacks on Afrin by Turkish-led forces between 22 January and 21 February killed 93 civilians, including 24 children.” Another comprehensive study published in August 2022 by the End Cross-border Bombing Campaign cited by CPT reported that “the Turkish Armed Forces… conducted at least 88 cross-border aerial, artillery, and ground attacks which caused civilian deaths and injuries within the borders of Iraq between 1 August 2015 and 31 December 2021.” These “eighty-eight attacks by the Turkish Armed Forces have caused the death of 98 to 123 civilians and non-belligerents of the conflict and injury of 134 to 161 civilians and non-combatants.”

Sweden and Turkey: The Political Economy of Normalization

Sweden has long cooperated with Turkey in various trade relations, extending to military cooperation. These trade and security relationships help to promote normalized relations between the countries. In 2011 Global Security reported that “in mid-2011 Turkey held separate talks with aeronautical officials from South Korea and Sweden for possible cooperation in the design, development and production of a new fighter aircraft in the next decade.” A report in 2013 discussed how “a special team consisting of experts and bureaucrats from aircraft industry companies was formed” in Turkey and that “this team went to Sweden and met with the SAAB management,” related to a potential military cooperation. A study by Solmaz Filiz Karabag and Christian Berggren, “International R&D collaboration in high tech – the challenges of jet fighter development partnerships in emerging economies,” published in the book, Handbook of Research on Driving Competitive Advantage through Lean and Disruptive Innovation, Advances in Business Strategy and Competitive Advantage (ABSCA) in 2016 states that: “Turkey has set a national goal of developing an indigenous jet fighter with its maiden flight planned to occur in 2023, and to accomplish this international collaboration is needed. The TFX-Saab is part of this effort, and has been highly important, at least in the concept development phase ending in late 2013.” Karabag and Berggren report that in 2013 Turkish Aerospace Industries “signed an agreement with SAAB, the Swedish Aerospace & Defense Company, to develop the TFX concept and plan the program…Although this contract was of a short-term nature, the two sides kept the door open for future joint development and production.” Another report in Military Wiki stated that “during a State visit of the President of Turkey to Sweden on the 13th of March 2013, Türk Havacılık ve Uzay Sanayii A.Ş (Turkish Aerospace Industries, TAI) signed an Agreement with Sweden’s SAAB” which stipulated that SAAB would “provide technological design assistance for Turkey’s TF-X program.” In 2018, Defence Turkey reported that under the “Concept Development and Preliminary Design Phase” or first phase of the TFX Program, Turkish Aerospace Industries “designated SAAB Aircraft Company as their Technical Support and Assistance Provider (TSAP).” This contract involved “a 24-month schedule that came into force on 29 September 2011, between September 2011 – September 2013, Prime Contractor TAI prepared three separate conceptual designs with technical support provided by SAAB Aircraft.”

In 2018, “Sweden sold nearly 300 million kronor worth of military equipment to Turkey,” with the sales including “electronic equipment, armor, software and technical assistance,” according to a Swedish Radio (SR) report based on ISP data. In October 2019, ISP “recalled permits for sales linked to military equipment, due to the Turkish offensive into northern Syria.” In October 2019, SR also reported that both “the government and parliament” announced that Sweden would push for an EU-level weapons embargo against Turkey at a meeting of EU foreign ministers.” One must then ask if this withdrawal and mobilization against Turkey was the exception to the rule of Swedish normalization of the Swedish state. Various pieces of data suggest that the isolation of Turkey was the exception.

One way to benchmark or measure normalization between a State A and another State B is to understand the opportunity costs of A supporting B. What does it mean when A holds itself up as a champion of feminism, human rights and social justice, but normalizes relations with B which supports the terror network ISIS? In the case considered, Sweden is A and Turkey is B. In 2014, The New York Times reported that ISIS recruited heavily from Turkey. An analysis on June 29, 2016 by Rukmini Callimachi at The New York Times confirmed Turkey’s links to ISIS: “From the start of the Islamic State’s rise through the chaos of the Syrian war, Turkey has played a central, if complicated, role in the group’s story. For years, it served as a rear base, transit hub and shopping bazaar for the Islamic State.” An International Peace Information Service (IPIS) report by Peter Danssaert on November 22, 2019 notes links between Turkey and armed Islamist groups in Syria: “The Turkish government has been accused of arming and assisting islamist armed Syrian groups. In 2015 the Turkish newspaper ‘Cumhuriyet’ published photographs and video footage of trucks allegedly under the control of the Turkish Intelligence Service (MIT) carrying weapons destined for jihadis in neighbouring Syria. It is alleged that Turkey has turned a blind-eye to islamist jihadis crossing the Turkish-Syrian border. Brett McGurk, the former Presidential Envoy to the International Coalition to Defeat Daesh, had this to say on Twitter: ‘Tal Abyad, a Syrian border town, was the main supply route for ISIS from 6/14-6/15 when weapons, explosives, and fighters flowed freely from Turkey to Raqqa and into Iraq. Turkey refused repeated and detailed requests to seal its side of the border with US help and assistance.’ McGurk acknowledged that some of the Turkish-backed opposition groups, who had received military aid from the U.S., had previously given their military equipment to al-Qaeda in Syria.”

While Turkey announced military operations against ISIS in Syria in August 2015, this hardly mitigates the other links between Turkey and ISIS. Earlier in 2015, Michael J. Totten reported in the Fall 2015 issue of World Affairs that Turkey’s leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan “was enraged when Kurdish forces in Syria liberated the town of Tel Abyad from ISIS.” As a result, “the Turkish military drew up a plan to invade Syria, not to fight ISIS but to set up a 30-kilometer-deep buffer zone to prevent the Syrian Kurds from controlling their own home country.” Sweden’s regulatory regime with respect to Turkey has essentially been totally meaningless aside from dramatic moves made which are later obliterated by later backtracking.

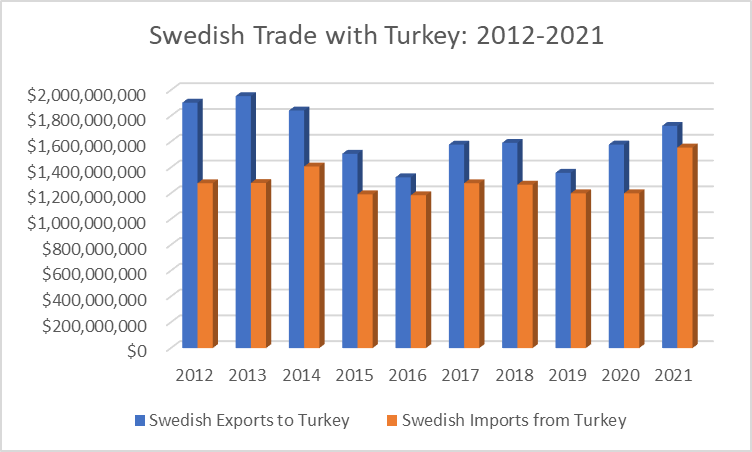

Despite The New York Times report linking Turkey to ISIS in 2016 (and earlier indications in 2015), Sweden sold 300 million SEK of military goods to Turkey in 2018. In fact, Sweden continued to import billions of dollars of worth of goods in 2016, 2017, and in the following years, despite Turkey’s links to ISIS (see Figure below). On a website post, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs explains the history of linkages as follows: “Bilateral relations between Turkey and Sweden have gained ‘strategic’ character with the signing of the ‘Declaration of Strategic Partnership’ in 2013. The bilateral trade volume between Turkey and Sweden was 3.212 billion USD (Turkish exports 1.481 billion USD, imports 1.731 billion USD) in 2018. Turkey’s main export items to Sweden are motor cars, vehicles for the transport of goods and chromium ores, while Turkey’s main import items from Sweden consist iron ores, paper and paperboard coated with kaolin, ferrous waste and scrap and medicaments.” On August 14, 2014, a Declaration on the Establishment of Joint Economic and Trade Committee (JETCO) between Turkey and Sweden was signed. The Ministry report identified other ways in which Sweden’s relationship with Turkey was normalized: “The number of Swedish tourists visiting Turkey amounted to nearly 385 thousand in 2018, corresponding to a 33% increase compared to the previous year.”

Over the last ten years Swedish trade with Turkey has involved tens of billions of dollars according to UN Comtrade data analyzed by the author. For the last ten years Sweden has actually been a net exporter. From 2012-2021 Sweden exported $16,352,801,271 worth of goods to Turkey and imported $12,838,342,246 worth of goods from Turkey. Thus, Sweden had a net trade balance with Turkey worth more than $3.5 billion dollars. Sweden’s foreign policy security could be linked to its trade with Turkey, but given that security considerations (for Sweden) are the penultimate regulator of Swedish arms exports decisions, there has been a long-time incentive for Sweden to export weapons to Turkey, even prior to Sweden’s attempts to join NATO. This incentive is based on the incentive states have to sell weapons to major trading partners. When Sweden threatened to cut off military sales to Saudi Arabia, various Swedish business interests reacted negatively. Much of Sweden’s wealth is based on trade with other nations. According to the World Bank, trade represesented 42% of GDP in 1960 but 88% in 2021. Unless a substitute economic activity is found for cutting off trade with a given nation, disposing of human rights is often the accepted recourse. In some cases, a military sale can be blocked or a military partnership can be ended. Yet, repeating such embargoes becomes more costly with each new cessation of a trade partnership.

In 2017, Sweden’s foreign minister, Margot Wallström, noted Sweden’s concerns about human rights developments in Turkey according to a Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs post. The case involved “the Swedish human rights activist Ali Gharavi and the continued detention of him and the other activists arrested in Turkey on 5 July” of that year. This episode had no impact on the accelerating Swedish tourist trade in Turkey or the billions of dollars in bilateral trade between the two nations in the years to come. In August 2017, Wallström explained that “developments in Turkey [were] very worrying and the negative trend we have been seeing for several years now has recently accelerated.” She explained that Sweden was “working constantly to strengthen respect for human rights in Turkey.” The problem, however, is that Wallström’s concerns were not matched by changes in Sweden’s trade or security policy stance towards Turkey as evidenced by the aforementioned 2018 military sales to Turkey.

Legislation as Displacement: Looking Good while Allowing Loopholes that Facilitate Weapons for Anti-Democratic, Human Rights Violators

In 2018, the Swedish government discussed “stricter control of military equipment.” Government Communication 2018/19:114 stated the following: “In October 2017 the Government presented the Government Bill Stricter Export Controls for Military Equipment (Govt Bill 2017/18:23) to the Riksdag with proposals for a number of stricter requirements in military equipment export controls. The Bill largely implements the proposals submitted by the parliamentary Supervisory Committee for Military Equipment Exports in its final report (SOU 2015:72). The Bill proposed that the democratic status of the recipient country should be a key condition in assessment of licence applications. The worse the democratic status, the less scope there is for licences to be granted. If serious and extensive violations of human rights or severe deficits in the recipient’s democratic status occur, this poses an obstacle to granting licences. Assessment of applications for licences must also take account of whether the export counteracts sustainable development in the recipient country. In addition, the principles for follow-on deliveries and international partnerships are clarified. Strengthened supervision, sanction charges for certain contraventions of the rules and greater openness and transparency on issues relating to military equipment exports are also proposed.” (Emphasis added).

This policy apparently triggered a ban on arms exports to Turkey earlier as Reuters recently reported: “Sweden and Finland effectively banned arms exports to Turkey in 2019 after its incursion into Syria against the Syrian Kurdish YPG militia, with ISP revoking existing permits and granting no new ones since then though no formal embargo existed.” The Reuters report noted that ISP “began giving export permits during the third quarter but did not reveal which companies or products had been given the go-ahead, citing confidentiality.” Turkey gained knowledge of Sweden’s favorable approach as early as May 2022.

In the following document, “Government Communication 2019/20:114 Strategic Export Controls in 2019 – Military Equipment and Dual-Use Items,” we find this statement: “Under Section 1, second paragraph of the Military Equipment Act (1992:1300), military equipment may only be exported if there are security or defence policy reasons for doing so, and provided there is no conflict with Sweden’s international obligations or Swedish foreign policy.” This suggests that Swedish foreign policy shapes the legality of an arms export, with the foreign policy here being a country trying desperately to join NATO. The same document states the human rights should be an important guide to arms export policy, an apparent contradiction in the case of Sweden’s exports to Turkey: “The review by EU Member States of the implementation of the EU’s Common Position on exports of military technology and equipment (2008/944/CFSP) and its user guide was completed in 2019…Among other things, Sweden pressed for texts on democracy to be inserted into the sections of the user guide concerned with the situation of a recipient country with regard to human rights and respect for international humanitarian law. There are now new texts of this kind at three places in the revised user guide.” Yet, given Sweden’s new policy on arms exports to Turkey, these insertions meant absolutely nothing and appear to have been a public relations exercise or a sincere sentiment (until it was displaced by new strategic considerations).

In the aforementioned Government Communication, we learn that 2019 was supposed to be “an important year for the ISP to follow up and continue to implement the stricter and modernised Swedish regulatory framework for exports of military equipment, Stricter Export Controls of Military Equipment (Govt Bill 2017/18:23 ‘the KEX Bill’), which with broad parliamentary support came into effect on 15 April 2018. The background to the stricter regulatory framework is that development over recent decades in the areas of foreign, security and defence policy has led to changes in the circumstances for and requirements to be met in Swedish military equipment export controls. The stricter regulatory framework largely reflects the proposals submitted by the parliamentary Supervisory Committee for Military Equipment Exports in its final report (SOU

2015:72). It follows from the amended regulatory framework that the democratic status of the recipient country should be a key condition in assessment of licence applications. The worse the democratic status, the less scope there is for licences to be granted. If serious and extensive violations of human rights or severe deficits in the recipient’s democratic status occur, this poses an obstacle to granting licences.” (Emphasis added). Again we learn that there is a barrier established, but Swedish foreign policy considerations merely lead the government and its regulatory agency to hop over the barrier.

Sustainability is supposed to be a consideration for Swedish military sales, i.e. the ecological impacts of a Swedish military sale to a recipient state. The aforementioned communication clearly shows a very superficial understanding of how to advance sustainability. This understanding governs the actions of firms, not necessarily government policies which retard the capacity to act sustainability: “There is a clear expectation on the part of the Government that Swedish companies will act sustainably and responsibly and base their work on the international guidelines for sustainable enterprise, both at home and abroad. A number of measures have been taken to encourage and support companies in their work on sustainability. Among other things, new legislation on sustainability reporting for large companies, clearer criteria for sustainability in the Public Procurement Act and stronger legal protection for whistleblowers have been introduced.” In other words, the impression left is that if a Swedish firm sells a fighter jet using clean fuel and sells that to an authoritarian regime, this sale would still be “sustainable” by the definition above. One could argue that democracy criteria would also intervene, but seeing as they don’t in Turkey’s case the impression left still stands.

The communication does refer to language that clearly makes weapon sales to Turkey difficult according to the EU’s Common Position on Arms Exports. This “common position” refers to EU Member States’ “national rules concerning the export of military equipment” and how “the Member States have also chosen to some extent to coordinate their export control policies.” Criterion Two of the “common position” concerns “respect for human rights in the country of final destination as well as respect by that country of international humanitarian law.” Thus, “export licences are to be denied if there is a clear risk that the military technology or equipment to be exported might be used for internal repression.” In 1999, the Washington, D.C.-based Institute for Policy Studies reported: “Turkish forces have used U.S. arms to commit human rights abuses, and the U.S. government does not have the ability to prevent future arms exports from being used in this manner.”

The Human Rights and Democracy Deficit

In 2021 Amnesty International reported on human rights in Turkey as follows: “Deep flaws in the judicial system were not addressed. Opposition politicians, journalists, human rights defenders and others faced baseless investigations, prosecutions and convictions. Turkey withdrew from the Istanbul Convention. Government officials targeted LGBTI people with homophobic rhetoric. Freedom of peaceful assembly was severely curtailed. A new law unduly restricted freedom of association for civil society organizations. Serious and credible allegations of torture and other ill-treatment were made. Turkey hosted 5.2 million migrants and refugees, but thousands of asylum seekers were denied entry. Physical attacks against refugees and migrants increased in the context of rising anti-refugee rhetoric.” In other words, Turkey has a poor human rights record.

On February 10, 2021, the Stockholm Center for Freedom reported that Turkey ranked “103rd among 167 countries” according to the Economist’s Intelligence Unit’s EIU’s Democracy Index 2021. The Center stated “the ranking of the index, which scored 167 countries from 0 to 10, was based on 60 indicators across five broad categories: electoral process and pluralism, the functioning of government, political participation, democratic political culture and civil liberties.” The Center referred to the Deutsche Welle Turkish service taking note that Turkey’s score of 4.35, fell under the category of a “hybrid regime,” which was the second-lowest ranking after an “authoritarian regime.”

The BTI Turkey Country Report for 2022 reported the following: “In domestic politics, authoritarian trends in the ‘New Turkey’ have been consolidated. After the lifting of the post-coup state of emergency in July 2018, several legal provisions that restricted fundamental rights and granted extraordinary powers to the executive were integrated into law. The rule of law has further deteriorated. The implementation of the amended constitution and the propagation of a presidential system have largely undermined fundamental aspects of a democratic system.”

Max Fisher at The New York Times reported on Turkish democracy in the following way last month in an interview: “Elected leaders rise within a democracy promising to defeat some threat within, and in the process end up slowly tearing that democracy down. Each step feels dangerous but maybe not outright authoritarian — the judiciary gets politicized a little, some previously independent institution gets co-opted, election rules get changed, news outlets come under tighter government control. No individual step feels as drastic as an outright coup. And because these leaders both promote and benefit from social polarization, these little power grabs might even be seen by supporters as saving democracy. But over many years, the system tilts more and more toward autocracy.” In sum, Turkey is deficient in democracy in a very serious way.

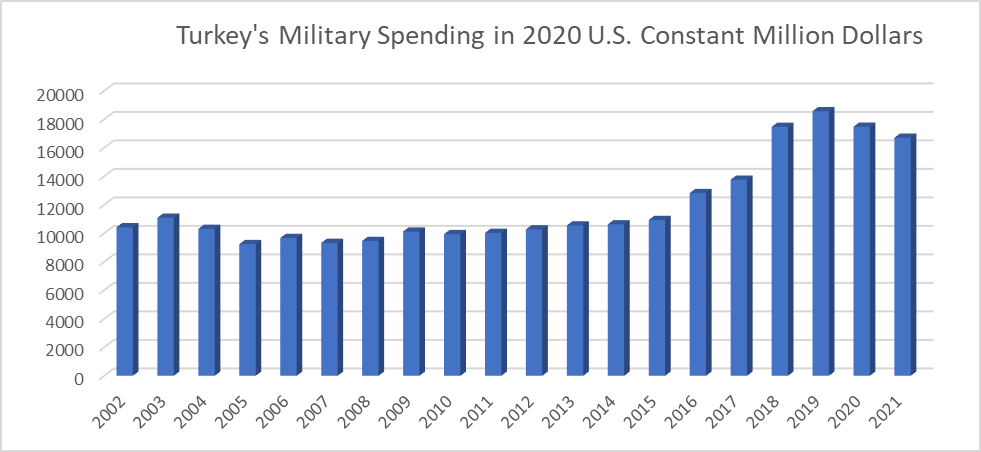

The Deficit in Sustainability and the Surplus of Gross Militarism

Swedish arms trade policy now supports a Turkish state which is mobilizing miltarily at the expense of positive ecological transformation. Turkey’s ranking in the current Environmental Performance Index, managed by Yale and Columbia Universities, was 172, with a score of 26.30. In comparison, Sweden’s rank was 5, with a score of 72.70. Turkey’s ranking was lower than Saudi Arabia’s, with this country having a rank of 109 and a score of 37.90. As can be seen in the figure below, Turkey has steadily increased its military budget, based on data compiled by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). During the last twenty or so years (from 2002 to 2021), Turkey’s military spending amounted to 238.8 billion dollars (in constant 2020 U.S. dollars). These funds represent an opportunity cost against investments in sustainable development as would any arms purchases from Sweden.

One might argue that Turkey needs a large military budget for self-defense, yet in May of this year Turkey threatened to invade the sovereign state of Syria. This threat did not deter ISP and the Swedish government from authorizing future weapons exports to Turkey. In May of this year, Yousif Ismael reported the following in a blog post connected to the Washington Institute for Near East Policy: “On Monday, April 18, the Turkish military launched a new invasion into the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), deploying ground and air forces into the mountains. As with previous incursions, Turkey used the pretext of fighting the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) to explain its entry into Kurdish territory. However, Turkey has established permanent military bases and posts after each military campaign since 2018. These bases are catalogued in a 2020 map released by the Turkish presidency, pinpointing forty military bases inside the KRI.” Despite such Turkish expansionism, Sweden has still authorized weapons sales to Turkey and is now part of Turkey’s militarism, a militarism which represents an opportunity cost for sustainable development and also a barrier to further democratization of the country. Ismael notes: “Turkey also sided directly with Azerbaijan when it launched a war on Armenia in Nagorno-Karabakh.”

Sweden’s arms sales to Turkey are an inducement to Turkish militarism and thereby part of the larger process of diminishing Turkey’s democracy. Hakkı Taş in a 2020 paper, “The New Turkey and its Nascent Security Regime,” (GIGA Focus Nahost, 6). Hamburg: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies – Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien, Institut für Nahost-Studien, reports that “Erdoğan is diversifying the country’s military and paramilitary instruments in both domestic and foreign politics as a strategy of coup-proofing and regime survival.” Taş argues that a key “dimension of Turkey’s ongoing transformation” is “the emerging security regime enhancing the state’s coercive capacity in all facets of domestic and foreign politics.” Within Turkey the army intervened “in politics almost every decade (in 1960, 1971, 1980, 1997, 2007, and 2016), albeit in different forms.” The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has micro-engineered the army, “leading to increasing politicisation across military ranks.” As a result, “overiding professional norms and meritocratic promotion based on competence and seniority, officers’ career trajectories have increasingly been aligned to favourable ties to the political leadership.” Any foreign support of Turkey’s military must account for how Turkey’s militarization is part of a process of de-democratization. Taş explains “from the suppression of the Kurds in southeast Anatolia to foreign military interventions, Ankara has increasingly resorted to coercive power.” Although the “investment in military power in a war-torn, fragile region reflects a rational calculation, the ruling AKP elite has deliberately adopted the militarisation of domestic and foreign politics as a strategy to consolidate the regime.”

The linkage between militarism and de-democratization was noted by Garo Paylan, a member of the Turkish Parliament in an opinion piece in The New York Times two years ago entitled, “How Turkey’s Military Adventures Decrease Freedom at Home.” Paylan noted that “involvement in regional conflicts such as the dispute between Azerbaijan and Armenia has whipped up nationalist fervor and obliterated space for advocates of peace and democracy.” Sweden’s arms sales to Turkey enable such interventions, thereby encouraging “nationalist fervor” which limits not only peace but democracy. Paylan explained then that “after a decades-long fitful truce, the conflict over the status of Nagorno-Karabakh — a breakaway Armenian enclave in Azerbaijan — between Azerbaijan and Armenia resumed last month” and led “to a large military deployment, destruction of civilian centers and thousands of casualties.” Turkey “supported Azerbaijan with defense technology, drones and propaganda machinery.”

Conclusions

The authorization of weapons sales to Turkey is a strike against democracy, sustainability and peace. Sweden has enabled (aided and abetted) a militarist state which tramples on human rights at home and abroad. ISP’s decision is immoral and might be considered illegal (or contradicting other aspects of Sweden and the EU’s policies) as well if the original legislative moves to regulate arms shipments meant anything. They apparently do not. They were originally deployed as part of a “do good” public relations exercise before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the new political climate linked in part to NATO’s eastward expansion has changed everything. Now freedom and democracy are simply commodities which some (like Swedes and Ukrainians) are entitled to and others (like Kurds) are not. This problem has occurred before and over and over with Swedish weapons aiding less democratic regimes in India, Pakistan, the Philippines Saudi Arabia, and Thailand, among others.

In conclusion, Sweden’s “moral” rhetoric on arms exports became even more rapidly disposable as a material reality when other priorities, such as joining NATO, gained in importance. Yet, it is far from clear that the decision to join NATO has improved the country’s security on many different metrics, e.g. potential future location of NATO’s nuclear weapons in Sweden, ecological security within Sweden, the capacity to fight criminal gangs that reap havoc in various neighborhoods, or the provision of a diplomatic way out of the Ukraine-Russia war. NATO membership is not the only issue at work here, however. In 2003, Sweden helped bomb Iraq. Sweden has also supplied weapons used in the Yemen war, something which has nothing to do with NATO. The overarching problem is the dilution of concerns for disarmament when it comes to Swedish conventional arms exports policy.