By Jonathan Michael Feldman Version: September 3, 2013

Introduction

We are heading for ecological and resource implosion if we don’t engage in a radical change in course. This essay is designed to promote new ways of thinking regarding how we should respond to various economic, energy and environmental crises. The ideas are based on the work of various scholars, discussions with activists and tracing through new political developments in contemporary social movements. In recent times, some new strategies have been adopted that represent important breakthroughs in terms of more systemic solutions to contemporary problems. In other words, grassroots movements are responding to structural barriers with strategies that redirect power to the grassroots and away from incumbent power tied to elites. These strategies work in both theoretical terms (in the sense that they get to the root of the problem) and organizing terms (in the sense that they offer people operational steps of what they could do next). It is clear, however, that these alternatives can be brought together in new ways and that not everyone is equally interested in putting political energy into these alternatives. Some of these alternative approaches, like cooperatives, are not even new, but they have gained renewed interest as the economic crises grows and incumbent policies fail.

Alternative Institutions are Needed

Elites seem confused or hindered in their attempts to solve the unemployment crisis. In countries like the U.K. and U.S., the super-rich if taxed properly, could solve much of their country’s problems. At the same time dysfuncitonal austerity policies are not the answer to the economic, energy or ecological crises and problems associated with a permanent war economy. The latter problems refer to societies that appear to prioritize military budgets serving military bureaucracies and arms contractors over and above basic security needs.

These needs include threats caused by the ecological crisis, economic security and even terrorism. For example, bombing campaigns in the Middle East inevitably create a terrorist backlash by providing propaganda for terrorist sympathizers in the form of civilian victims. The deaths of such civilians are tragic enough, but the tragedy is compounded when groups rally around these victims to perpetuate the cycle of violence. Of course, not everyone agrees on who is a terrorist and who is not. The larger point is that militarist policies (like bombing civilians) are generating more terrorists than political and military leaders acknowledge.

Some economists understand the need for an economic stimulus, rather than just cutting taxes. They understand that if aggregate demand is not increased, then growth won’t happen. Cutting taxes won’t be enough to get people to buy. These economists prioritize government spending rather than fiscal austerity because they realize such spending can create jobs and growth. Yet, those who simply prioritize economic demand fail to explain in great detail why simply increasing demand is insufficient.

First, the form of economic demand taken by defense spending can create fewer jobs than civilian spending. Second, economic demand is weak in part because wealth creation capabilities have eroded: deindustrialization and other factors reduce income, purchasing power and employment that shapes demand. Third, they link demand too much to government spending but fail to see how domestic demand is lost to imports, i.e. people are demanding things from outside the country, not creating many jobs at home but more abroad. Finally, we have too much demand for designs, products and technologies destroying the planet, i.e. we need sustainable demand.

We could and should tax the super-rich more to promote alternative policies. There are, however, certain problems with this approach. First, companies like Goldman Sachs are major campaign financiers and lobbyists. They therefore make claims on certain politicians who (all things being equal) respond to the stimuli of such donations or share their ideology. Sometimes political movements can help change the calculations of these politicians, but not always. In any case, in countries like the U.S. and U.K. the members of the political elite tend to listen to and be vetted by the members of the financial elite. We need to avoid “magical thinking,” the idea that saying something enough times makes it happen.

Second, it’s not certain that politicians will use tax money that they receive wisely. Some parties cut social spending and preserve the bloated military budget. Or, they invest in the wrong kinds of policies: policies that harm civilian manufacturing, green investments, and the welfare state but promote the irresponsible parts of financial sector and the military-industrial complex.

Third, too many policy analysts and activists have treated “equitable taxation” as an independent variable (or causal element), when it is a dependent variable (or dependent on other factors being in place first). Saying you want to increase taxes on the super-rich may give you some power to do so, but an insufficient level of power. We have to accumulate the scale of economic, media and political power necessary to reshape the state and also create direct alternatives that bypass dysfunctional politicians.

More comprehensive alternatives are therefore needed to address the triple crisis which Barry Commoner, Seymour Melman and other thinkers warned us about long ago. Both alternatives and complements to the system are needed. The alternatives take the form of new institutions and organizational innovations. That is to say new kinds of institutions that provide for citizens’ needs without intermediaries that dilute the public interest. These intermediaries include big banks that overcharge their patrons and basically gamble with clients’ money. They also include utilities that don’t promote more sustainable forms of energy. This tradition, called “reconstructionism,” dates backs to thinkers like Thorsten Veblen and is embodied today in the ideas of intellectuals like Gar Alperovitz and Noam Chomsky.

The Economic Crisis Requires Organizational Innovations that Can Be Blocked by Repression and the Sometimes Celebratory Political Culture of the Left

It’s clear that the current wave of democracy movements have been far more successful than their more recent predecessors but the extent of the crises we now face ups the ante somewhat. For example, labor activists of the 1930s and 1940s battled for labor rights, against depression and fascism. Yet, the depression crisis was largely a problem of demand, not supply. The U.S. had the domestic capacity to supply domestic needs, but today does not have all the necessary productive capacity (which has been extensively lost to outsourcing and deindustrialization).

The New Deal did not create a sufficient base for a peoples’ economy outside the state. In the present period, as Seymour Melman explained, many larger established businesses are “abdicating the organization of work,” because it is mobile, because people don’t own or control their jobs, because the criterion of producing the most profit outweighs the criterion of producing the most jobs. Moving forward, the antiwar protesters of the 1960s faced a problem of an irrational war in Vietnam, racism, and sexism but lived in a period of relative economic abundance. Despite economic inequality, economic austerity seemed less severe, particularly for the so-called “middle class.”

Today, protesters must confront problems associated with war, rapid ecological decline, economic inequality, extensive mismanagement of the economic base, student debt and the like. One could argue that the problems of the 1930s and 1940s were more severe than the problems facing us today. Yet, the organizing strategies of the movements of that era had elements that are only slowly being recovered by contemporary movements, with this lag being a problem induced by the design of New Left movements, e.g. the Old Left was able to advance ideas related to class and economic welfare to broad numbers of people. The New Left was often more concerned with the poor than with a larger class of people. The problem was not that the New Left showed concern for the poor. Rather the problem is how poor peoples’ interests were advanced. For example, W. E. B. Du Bois from the Old Left supported cooperatives to enhance the economic status of African Americans. This idea did not gain much currency within the New Left, although the New Left did seek to overcome the Stalinist and authoritarian tendencies of the Old Left. The New Left re-ignited the antiwar movement, but some of its early founders had larger ambitions for developing a democratic economy that were lost to the “community organizing” project of key activists. This project had strengths and weaknesses, with the weaknesses often enough ignored.

By organizational innovations, I mean that social movements must continually re-invent themselves. They can’t be caught in a cycle that unconsciously repeats the patterns of prior social movements, without learning about their limits. The last large social movements that hit the United States, Western Europe and elsewhere had strengths and weaknesses. Some of these weaknesses were understood and others were not. If we don’t understand the past, we are condemned to repeat it as the saying goes.

Why isn’t this past understood? First, the limits of prior social movement routines are hidden in part by a celebratory revisionism that exists within academic life, e.g. among many intellectual treatments of the New Left that misappropriate the past because of conflicts of interests. Participants in these movements sometimes wisely recount their strengths and weaknesses, but sometimes they don’t. The left is able to “filter” facts the same way the established media does. The French philosopher Simone Weil honestly confronted the limits to the left as well as those on the right (albeit from what might be called a “radical” perspective). So, what is at stake is not a celebration of the “center” but an understanding of different intellectual trajectories among more critical intellectuals, social movements and projects.

Second, a “cheerleading culture” permeates many treatments of social movements because of exigencies associated with book publishing, access to media channels engaged in celebratory politics, access to sources (in this case social movement participants), and a form of anti-intellectualism that permeates many societies today. If the right often thinks that the system justifies itself by its existence, the left sometimes uses the same logic. These existences are of course contingent upon someone’s choices as social movements are authored by “key persons” even in formally democratic or consensus-based movements. Repressing the authorship, responsibility and design choices of these “key persons” will prove counter-productive in the long run. The left is affected by capitalism as some astute observers have acknowledged.

Third, the pedagogic process which can explain systematic alternatives has broken down or weakened. One problem is the weakening of utopian thinking, in the sense of thinking about alternative models, although some circles in the Occupy and new economy movement have revived or expanded such thinking. Some elements, but not all, of postmodernism have been construed in such a way to actually block any systematic thinking about economic democracy. The reconstructionist ideas about cooperatives, industrial policy, and democratic planning never gained hegemony in the university system in the postwar era and were even marginalized within many circles within the left. One reason was that the Great Depression and the later failure of apparent reform initiatives made such ideas (like critical institutionalists) appear to be dead ends. At the same time, the successes of industrial policy and alternative planning within corporations (e.g. the few post-Vietnam War era civilian diversification successes by defense firms to make civilian products) have been subject to the “Big Lie,” i.e. reality was ignored or debunked by many in the mass media, various policy analysts and some academics.

I am simply referring here to tendencies within contemporary movements or the media that are not monolithic but are nevertheless systemic. This means these problems show up and create problems, even if they are not always fully articulated. If the above analysis seems convoluted or vague, the message is simply this. If large parts of the world enter a major economic crisis, social movements that don’t begin “delivering the goods” may become marginalized by far right movements that make pie in the sky promises to do so. They will claim to solve economic problems with tax cuts and shrinking (civilian) government. Or, such far right movements will continue to use immigrants, Arabs, Jews, gays, etc. as scapegoats so as to divert attention from failed economic, political and cultural structures. They will gain “political capital” from political repression campaigns as Richard Nixon and others have done.

Political repression extends to the academic sphere as those with more critical ideas can be screened out and marginalized. This tradition is rather long in history. It is the story of Galileo and Socrates. It’s been addressed by various thinkers in the United States including Randolph Bourne, Noam Chomsky, Ellen W. Schrecker and David Noble.

One then wants to ask, “Why don’t social movements always deliver the goods?” The hypothesis offered here is that such movements are not simply facing repression and weak resources. They are also on a path that diminishes their resources by having poor designs. Alternative designs are therefore necessary. Michael Lerner coined the phrase “surplus powerlessness” to explicate some of these ideas.

The Politics of Design

As noted, the critique offered here on the far right and the left is not meant to advocate some critical centrist position. Rather, it is designed to recapture the historical trajectory that lies behind certain left or critical ideas and show how these particular ideas are part of choices that were made which might be wrong. Jean-Paul Sartre long ago argued against mechanical Marxism and the left’s failure to recognize the open-ended nature of politics. But what we also want to avoid is a kind serial legitimization of every new idea that the left comes up with. To a certain extent we need to embrace John Dewey’s notion that any idea has to be tested out to discover its merits. Yet, we live in a celebratory culture, with left celebrities (or critical intellectuals who are turned into celebrities) validated by various media, credentials and the like, whose pronouncements mean such tests can be short-circuited. Even “leaderless” movements are based on choices that may or may not be functional in terms of effectively challenging elites. A democratic process will be better than a non-democratic process all things being equal, but doesn’t necessarily guarantee good ideas. The creation of good ideas requires research programs that explore evidence, examine past intellectual works, and do things that don’t always happen in “real time.”

Left intellectuals, for example, need the media and engage in a scholarly world often based on more stringent evidence claims. Yet, when they enter or are filtered by the media spotlight this validation process is mitigated. The intellectual is marketing ideas they believe are important, but we know from the business world that not all products that are effectively marketed work after they are used for a period of days, weeks, months or years. If C. Wright Mills warned about the “cultural apparatus” (or the mass media, universities and others that potentially filtered out truth), today we must be wary of the “topicality apparatus.” Just because something is “topical,” does not mean that it is “important,” although it might be.

The necessity for tests means that we must assess the merits of alternative social movement designs (or alternative movement rituals, routines and strategies). In contemporary terms, the movement to consciously promote alternative designs within social movements can be traced to the work of Paul Goodman. Paul Goodman once wrote an essay called, “Designing Pacifist Films,” which provides a partial inspiration for informing my notions of the politics of design. The “politics of design” corresponds to questions of form (how information or symbols are conveyed, including their organizational platform) and questions of content (what information or symbols are conveyed, including the philosophy, ideology and capacity to integrate diverse ideas and forms of knowledge). For example, when it comes to the content of pacifist films, Goodman wrote: “such a film must at least not do positive harm by predisposing its audience toward war.”

When it comes to designing pacifist films, Goodman argues for three criteria: “(1) Factual education; (2) Analyses of character-neurotic and social-neurotic war ideology, and the withdrawal of energy from the causes of war spirit; (3) Opportunities for positive action, and pacifist history and exemplars.” Education is necessary to allow people to become informed about what could be done differently, what Goodman describes elsewhere as “utopian thinking.” Goodman writes that one must understand the sphere of necessity in positing a design to alternative it. In his words, “the immense network of the power structure must be made clear and diagrammed, so that a person comes to realize how nearly every job, profession, and status is indirectly and directly involved in making war.”

The psychological dimension is useful for assessing motives, particularly the energy invested in incumbent designs, i.e. the designs presently being used that could be reconfigured. The “opportunities for action” correspond to choices in general regarding what people could be done, the examples relate to models for action. This implies an assessment of alternative models and using multiple case studies of alternative designs. One can compare how different organizations or movements get power, which were more effective, more ethical and broadened awareness of realities best. One can point to examples of innovative ways to organize and promote economic alternatives. Creative organizing must end in alternative institutions, but we won’t see the growth of such alternatives without such creative organizing attempts.

Returning to the question of academics, the media, and topicality, one alternative design would be to combine the intellectual with mass media and then mediated examples or representatives of actual case studies of potential political and economic practices advocated by such intellectuals, e.g. alternative economic forms. Intellectuals could be tested by looking at examples of alternative practices. They can be tested by debates with other intellectuals. Or, they can be tested by engagement with audiences who (like intellectuals) may be more or less informed.

In The Sociological Imagination, C. Wright Mills, wrote: “The corporate economy is run neither as a set of town meetings nor as a set of powers responsible to those whom their activities affect very seriously. The military machines and increasingly the political state are in the same condition.” How did Mills believe individuals could advance their freedom effectively? He explained that: “What are required are parties and movements and publics having two characteristics: (1) within them ideas and alternatives of social life are truly debated, and (2) they have a chance really to influence decisions of structural consequence” (C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination, New York: Oxford University Press, 2003 [1959]: 188, 190).

The key question becomes how to create spaces that allow such debates and structural changes. One requirement is the creation of a certain kind of political form. The other is the creation of a certain kind of discursive content. Turning to the latter, Mills asked: “Where is the intelligentsia that is carrying on the big discourse of the Western world and whose work as intellectuals is influential among parties and politics and publics relevant to the great decisions of our time? Where are the mass media open to such men? Who among those who are in charge of the two-party state and its ferocious military machines are alert to what goes on in the world of knowledge and reason and sensibility? Why is the free intellect so divorced from decisions of power? Why does there now prevail among men of power such a higher and irresponsible ignorance?” (Mills, ibid.: 183). This question which Mills asked decades ago is still relevant, as evidence in the recent Syria crisis. In response to this crisis, we find the Left often asks questions that are too small to address underlying structures. In contrast, Mills argued that we have to ask big questions.

The Strategic Agenda

Among the core problems include the following. First, a central agenda item is the need to revive manufacturing in many states where growth has declined. The question is whether such a revival will come from transnational corporations that fail to pay their fair share of taxes or outsource work overseas.

Second, the political elites are beholden to economic elites that profit from the junking of economy in the long run, to make profits in the short-to-medium run. These political elites may support some measure of reform as they need votes to maintain their legitimacy and some ideologically want changes even though they often offer only piecemeal changes. To the extent they support rational changes like promoting alternative energy and mass transit, the system works. To the extent that the rate and extent of change is far from insufficient, we need new institutions external to the incumbent government and large transnationals to directly promote economic, political and economic capital that meets the larger public’s interests.

In summary, we need to create a new system within the old system that pressures the incumbent system to reform while it directly creates the new, more functional system we need. The far right is now using the government as a tool weaken the economy and strengthen the military/security part of the state and the less socially-responsible parts of the market. The far right uses big corporate money to alter the state and make the state accountable to its agenda. Similarly, we need to use our own kinds of political, economic, and media capital to make the state accountable to our agenda. Yet, we can’t just rely on the state to meet our needs because: (a) parts of the state are permanently wedded to dysfunctional interests; (b) the probability of reform diminishes when big money dominates politics, (c) the far right can capture the state and quickly undo many reforms; (d) often when the state works well, it is part of a corporatist coalition involving external actors that pushes it to work well, e.g. alternative energy firms that reshape government agency agendas for clean energy.

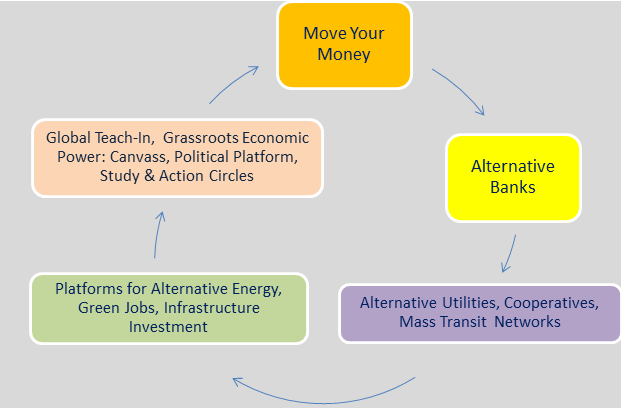

The Global Teach-In is based on the principle that by moving our money and pushing politicians to promote alternative banks and budgetary policies, we can begin a new political cycle from below and above that will promote alternative intermediary institutions. We can move our money out of established banks, corporations, military budgets and other institutions or expenditures working against us. The alternative institutions and budgets include: alternative utilities, cooperatives and mass transit networks. These democratic or public intermediaries can act as platforms for alternative energy, green jobs and green infrastructure investment. By creating jobs, saving consumers’ money, providing new services, improving environmental conditions and creating a base for popular citizen economic power, we will gain further resources for a green, democratic conversion of the political, economic and media spheres. This cycle shows how we can promote accountability systems, democracy and resources for civil liberties against centralized bureaucracies that are not responsive to public needs.

Conceiving Economic Reconstruction in Five Interrelated Stages

This virtuous cycle can start at any one point. For example, we could start by moving our money out of established banks and into alternative banks like the JAK, cooperative bank in Sweden. We need to exit banks that are part of predatory lending to students, as in the U.S. for example. Such alternative banks could begin to invest in: (a) alternative utilities back by campaigns to create them; (b) cooperatives organized on democratic principles in service and manufacturing industries, e.g. Mondragon; and (c) networks providing mass transit services or actually manufacturing mass transit products supported by various industrial policies. These alternative institutions and movements can provide platforms for: (a) alternative energy; (b) green jobs, and (c) infrastructure investment. The resulting capital, profit or resources generated by these energy systems, jobs and firms (economic capital) can be transformed into political capital that changes social conditions. This requires various kinds of political organizing campaigns and supporting pedagogic forms, like canvassing, study and action circles. The resulting political capital can be channeled into campaigns to release economic capital for a more democratic economy, like the Move Your Money campaign, thus completing the cycle. In some cases, labor unions, social movements or NGOs, launch campaigns to directly use their own resources to support alternative demoratic economic forms.

The ensemble of these alternative relations (highlighted above) has to be linked to some kind of secular and non-secular ethical system that promotes larger social values beyond the market and profit. This critical function comes partially from the kinds of deliberative, democratic values embodied in parts of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Yet, deliberative democratic processes are partially informed by value systems, hegemonic biases and other influences which require independent checks and influences.

For more information: click here, here and here.