Global Solidarity Requires Vigilant Whataboutism

By Jonathan Michael Feldman, July 23, 2023; Revised July 25, 2023

The Militarist Turn of the Left

Sweden is a useful test regarding how vigilant left parties are in opposing the militarism that props up mass murder, authoritarianism and anti-democratic forces. I argue that these parties’ efforts are often vaguely well-minded, but grossly inadequate. NATO propaganda and “solidarity” with Ukraine has crowded out other concerns. Narratives about Swedish government malfeasance are crowded out by a hard power nationalist juggernaut directed by homegrown militarists and elite apologists for the defense industry. Heroic opposition by such parties seems to have de-evolved into moral pleading without sufficient political engagement.

The leading parties help shape the media space for all other parties, often defining the boundaries on how much time, attention or focus critics of society have. Underlining all this is the alliance between NATO and the Swedish military. Ola Tunander wrote an important article which discusses a key foundation of these forces. In “Swedish Geopolitics: From Rudolf Kjellén to a Swedish ‘Dual State’,” Geopolitics, Vol. 10, Issue 3, he described the Swedish geopolitical scholar Rudolf Kjellén who “suggested that in the twentieth century various empires would eventually force Central Europe to unify into a bloc of states under the protection of a powerful Germany.” Tunander said that this concept “is also very similar to what later became NATO, but now with the United States, not Germany, as its central protecting power.” Hans Morgenthau described a “dual state” involving “a regular state hierarchy of the nation-state versus a parallel security hierarchy, now linked to the central power.” After World War II, “Sweden, despite its ‘policy of neutrality’, was placed under the US nuclear umbrella, creating a duality that typified Morgenthau’s idea of the ‘dual state.’” On the one side was “the regular ‘democratic hierarchy’” which on the other side “was confronted by the US-leaning ‘security hierarchy’, with the latter intervening in the event of emergency.” During the 1980s, “the strength and unpredictability of the Swedish Social Democratic government became worrisome to the US security network.” Today, NATO and the US help control Western and European politics, with leading parties subservient to or ratifying their militarist agenda. Left parties opposing these forces must oppose not only the hegemonic power of national militarists, but also the global hegemonic power of the US. This power involves US media, US military actors, and global trade relations involving the US, not to mention political exchanges with the US typified by Swedish engagement in the Atlantic Council.

Despite or perhaps because of these powerful forces, the left’s engagement is also thoroughly inadequate, one reason may be that asking critical questions yields little in a political and media environment dominated by NATO preferences and those subservient to its agenda. A poll published in July showed that only 2.8% of voters in mid-to-late-June supported the Green Party, although 8.7% supported the Left Party. This creates an environment in which “controversial” positions can be thoroughly marginalized. They might not pay off with respect to many voters’ preferences. Messages that must be exchanged for votes often involve the lowest common denominator because much of the media, politicians, and the military “dumb down” understandings of complex foreign policy questions (often assisted by academics or think tank operatives paid for by the state). Or, principled positions might lead to political suicide. The Social Democrats, the party with the most support at 34.1%, sidestepped NATO’s hegemonic power by embracing entry into the alliance. No political suicide required.

As many of us know, Russia is engaged in a vicious slaughter against the people of Ukraine. This recognition that some critics of Swedish militarism have is devalued by supporters of the war after the critics start asking questions as to why things came to pass. The other day I engaged in a social media debate with a former member of the Swedish parliament about the role of NATO in triggering the war in Ukraine. I suggested that it was false to suggest that NATO was irrelevant to triggering this war. My views on this matter are based on reviewing lots of material including one of the most important analyses of this question by Benjamin Schwarz and Christopher Layne in Harper’s, Why are We in Ukraine?, in the June issue. Andrew Bacevich at the Quincy Institute has made similar arguments to Schwarz and Layne. Some argue that Biden and the US wanted the war to try to effect regime change in Russia. I originally thought the person I was debating with was a Social Democrat or perhaps someone in a right-wing party who I happened to have befriended. The politician stated: “Worth underlining: Putin’s invasion of Ukraine had ZERO to do with NATO. The motive was to expand Russia’s territory, to create a larger empire.” I tried to correct this misinformation but was told, that I had “a lot of Russian propaganda” in my comments. Russia may like to expand, of course, but NATO likes to expand even more, even faster. The counter-argument is that NATO represents the “free world,” and “free choices,” but that’s belied by the railroading of NATO which did not involve any deep or authentic debate in Sweden and the very anti-democratic weapons transfers endorsed by the Swedish state (as chronicled below).

What surprised me most was that this former politician has been associated with Sweden’s Green Party, whose leading foreign policy spokesperson is actually against Sweden joining NATO. I have called for decentralization of power in Russia and expansion of democracy there. It is self-evident that Russia is engaged in a terrorist-like war campaign against Ukrainian civilians, an approach which basically replicates what Russia did to Chechnya as can be seen in photographic documentation published by the National Security Archive. In any case, my exchange with this allegedly “left” politician got me to wonder whether or not left parties actually have a capacity to critically engage in foreign policy questions.

In April of last year, Erik Pettersson, a reporter for Syre, one of the few anti-militarist news outlets left in Sweden, wrote a rather important article touching on this question. He explained that Maria Ferm, the Green Party’s foreign policy spokesperson, says the party would not change its mind and would not support joining NATO. In contrast, Anders Schröder, former defense policy spokesperson in the party, believed that Sweden should join NATO. The background to the party’s internal deliberations is that while the Green Party has its roots in the peace movement and has always opposed membership in NATO and Swedish arms exports, its board nevertheless supported military equipment shipments to Ukraine, including 5,000 anti-tank rounds.

I’ve tried to document the European left’s embrace of militarism in various articles. These include an analysis of arguments published by Daniel Marwecki and the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, the nominal anti-imperialist Gilbert Achcar, Daniel Suhonen who is a leading Swedish Social Democrat on the left, and as well as Swedish left parties’ embrace of the arms shipments to Ukraine. In each case, moralistic short-term thinking has concealed the Faustian bargain of allying with brutal militaristic forces triggered and encouraged by the US warfare state. Sweden had the historical opportunity to be a more critical third party force, pushing for diplomacy. Instead, with the aid of part of its left, it decided to be just another in a string of NATO satellites.

Arms Exports in General

My engagement with one of the Green Party’s NATO champions, or at least NATO’s version of the truth, led me to inquire as to what aspects of foreign policy Sweden’s left parties are able to consider. Three critical issues now are that: (a) Sweden recently authorized arms shipments to Turkey, (b) Swedish arms exports that have ended up supporting the war in Yemen and (c) Swedish weapons have endorsed and enabled the anti-democratic state in Thailand.

The Green Party is generally against weapons exports, aside from shipments to Ukraine. It has supported a stop of EU arms exports to dictators, peace cooperation, work for global disarmament, and an ethical requirement related to weapons exports. In 2007, three Green Party parliamentarians, Peter Rådberg, Bodil Ceballos, and Karla López (with Max Andersson and Ulf Holm) launched a parliamentary proposal Motion 2007/08:U230 entitled, “Swedish arms exports contribute to fueling wars and conflicts.” This important initiative is worth quoting at length (translated as follows): “We must do our utmost to free our peoples from the scourge of war which, in conflicts within and between countries, has claimed more than five million lives in the last decade. This declaration was adopted in September 2000 by the Millennium Summit organized by the United Nations. If Sweden and the countries of the world mean what they say, there must of course be consequences. Parts of the world are characterized by profound and complicated conflicts, which often lead to war and gross violations of human rights. The international arms trade is an important driving force behind military armaments, and thus contributes to wars and armed conflicts. Therefore, Sweden should work for a radical Swedish and global disarmament, and for resources that are currently wasted on military armor to be redistributed to efforts that can prevent wars and conflicts.”

For its part the Left Party has stated that in 2018 their party was the only one “that voted for an absolute ban on exports to dictatorships, states that are at war or commit gross and extensive crimes against human rights.” They also note that “exports to dictatorships, states that are at war or commit gross and extensive crimes against human rights are increasing with each passing year” and they also sought “to tighten the rules for importing, lending and renting military equipment.” These concerns are honorable, but without economic alternatives for the defense industry reformist proposals will likely go nowhere. This was recently proven in the case of Swedish government authorization of weapons sales to Turkey, a case of disposable morality explained in some detail below. The Turkish case revealed the Sweden’s attempt to regulate arms exports resembled an empty promise and public relations gesture.

Given left parties’ general platforms on arms exports and NATO, what problems arise? The key problem or limitation with the general opposition is that foreign policy currents within left parties are driven by the larger narratives shaped by competing parties, mass media, and the focal points monopolized by militarists and their experts attached to specific conflicts. For example, the Green Party’s website had 105 references to Ukraine, in contrast to the Left Party which had only twenty-six. As we will see, other conflict areas get less coverage. It is obvious that the brutal war, with its extensive damage and flood of news coverage and matching political moves explains part of this discrepancy. Yet while right-wing and militarist apologists always claim “whataboutism” when other conflicts are discussed, the problem is that the NATO militarist push has crowded out narratives about such conflicts. And some critics of US foreign policy argue that there are virtues to whataboutism when it concerns comparisons between Putin’s actions and U.S. militarism.

In the Swedish case it is clear that the dominant media narrative emphasizing solidarity with Ukraine, joining NATO, and the need to sell weapons to Ukraine, have all drowned out other competing narratives about Swedish transgressions against human rights in other countries, which include Turkey, Yemen and Thailand. Therefore, it is important to see how left parties treat these other conflicts and what narratives they construct—if any—around them. The militarist tendency within the Green Party linked to Russia and Ukraine, clearly shows one limit to generalist propositions about arms exports. The political capital of anti-militarists on the left (or right for that matter) are linked to the capacity to repeat narratives of transgressions against democracy and human rights in specific cases. If such narratives are missing, the general position against militarism will likely dilute and deteriorate. Militarist critics should not disarm themselves. Let us see how two Swedish left parties do in perpetuating alternative narratives related to just three cases: Turkey, Yemen and Thailand.

Turkey

Turning to the first case, the Institute for Strategic Products (ISP) provides authorization for Swedish weapons exports. In a September 30, 2022 statement, updated October 3, 2022, the ISP announced authorization of Swedish weapons exports to Turkey. This statement (translated below) reads as follows: “Sweden’s application for membership in NATO greatly strengthens the defense and security policy reasons for granting the export of military equipment to other member states, including Turkey. With regard to the changed defense and security policy circumstances, ISP has, after an overall assessment, decided to grant a permit for follow-on deliveries from the Swedish defense industry to Turkey. The permit concerns other military equipment within the categories ML11 (electronic equipment), ML21 (software) and ML22 (technical assistance)….The decision to grant permission for follow-on deliveries to Turkey has been preceded by consultation with the Export Control Council.”

The ISP decision came about two weeks after the UN reported that Turkey may have committed war crimes in Syria and reports a few months earlier about Turkish attacks on civilians in Iraq. Levent Kennez in an article the Nordic Monitor (September 16, 2022) explains: “the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic…in a report published on September 14” referred “to mortar shells that may have been fired from Turkey and several drone attacks killing civilians at various times in 2022.” Another report in Middle East Eye described a Turkish attack in August 2022 as follows: “At least 15 civilians have been killed, including five children, and 30 others wounded in government shelling that hit a busy market and other civilian buildings in the Turkish-controlled city of Al-Bab in northern Syria.”

The Green Party’s website had twenty-four references to Turkey, in one such reference they argued that Sweden should not “adapt its foreign policy to the demands of authoritarian states in order to become a member of NATO and that Sweden should not start selling weapons to Turkey.” The Left Party website had twenty-eight references to Turkey. In one such reference they pointed out, how “the party leader of the pro-Kurdish party HDP and nine other parliamentarians were arrested in Turkey” and condemned “Turkey’s undemocratic actions” and demanded “that Sweden’s foreign minister immediately summons Turkey’s ambassador and then acts to stop the EU negotiations with Turkey.” That was in 2016, however. In a later post, the party declared, “we do not want to see the government make concessions to Turkey that go against fundamental Swedish values” and “we will always stand up to that.”

In sum, these parties correctly point out the limits to engaging with Turkey and the human rights costs of doing so. Yet, they offer very few specifics about Swedish engagement with such arms exports, aside from a moral condemnation. In contrast to Ukraine coverage, the Green Party appears circumspect. An earlier condemnation by the party of arms exports to the country is not followed up on in a consistent way.

Yemen

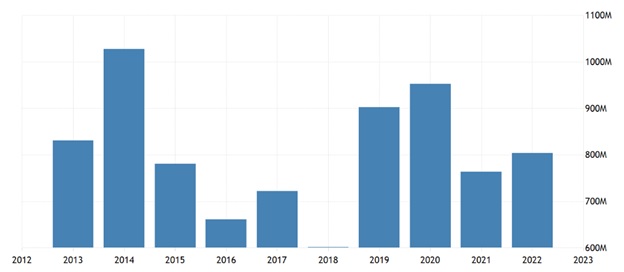

Turning to the second case, Swedish weapons have used in the conflict in Yemen. This linkage has been documented by Swedish television channel TV4 and circulated by the Swedish Development Forum and Vijay Prashad in Salon. An August 13, 2019 report by Thea Mossige-Norheim in Dagens Nyheter identified various military items linked to satellite images of the port Assab in Eritrea, “strategically important for, among others, the United Arab Emirates.” Images identified “patrol ships with a cannon made by Swedish Bofors…ships from the Swedish company Swede Ship, armed with cannons and missiles” and “also armed ships with radar systems from Saab.” In 2018, Afrah Nasser wrote in Open Democracy that “despite the documented crimes of the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, Sweden continues to sell arms to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.” Nasser noted that “between 2010 and 2016, the arms sales to Saudi Arabia was worth almost 6 billion Swedish kronor.” Figure 1 identifies the pattern of Swedish weapons exports to United Arab Emirates, which entered the Yemen conflict in 2015. By the end of 2021, the war in Yemen was expected to have killed 377,000. In December 2022, UNICEF reported that more than 11,000 children were killed or injured in Yemen. In 2021, Sweden sent $80 million worth of weapons (in 1990 US dollars) to United Arab Emirates; the country pulled back from its military engagement in Yemen in 2019, but not completely according to a February 2022 report.

Figure 1: Swedish Weapons Sales to United Arab Emirates

Source: Trading Economics, 2023 using Comtrade Data.

The Green Party website had only five references to Yemen. One key reference (which linked to an editorial by Green party member Bodil Valero, the aforementioned Bodil Celabos) argued that Sweden needed “to freeze its exports to Saudi and its allies” and that the parties and parliament’s EU Committee “can and should immediately put the issue of a Swedish and European arms embargo on their agenda.” Valero clearly made the connection between human rights and Swedish arms exports. Valero sponsored the earlier discussed Motion 2007/08:U230. The motion stated the following: “Saudi Arabia is one of the world’s most brutal dictatorships, and in its own report the Ministry of Foreign Affairs strongly criticizes the lack of respect for human rights. It is not allowed to publicly criticize Islam or the royal family. Political parties are banned and demonstrations are illegal. In accordance with Shariah, corporal punishment is imposed in the form of flogging and amputation. The death penalty is applied. In 2005, Sweden signed a far-reaching military cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia.” Yet, ten years later (June 2015), Peter Eriksson the former Green Party leader, criticized then party leader Åsa Romson and others in his party “for their reluctance to call Saudi Arabia a dictatorship.” In contrast, the Left Party’s website had only one reference to Yemen, which referenced refugees fleeing the conflict there. There was nothing about arms exports and Sweden’s role. The Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI) attempted to build a weapons factory in Saudi Arabia starting in 2007 but was exposed in 2012 and thwarted.

In sum, the Yemen case shows a deficit in the Left Party’s engagement on the Yemen question, at least as reflected in their website. The Green Party’s Valero makes the essential arguments and her efforts on Yemen seemed to have had wide coverage in . But this engagement does not appear to have been followed up on in a consistent matter. Eriksson’s observations identify a clear de-evolution of Green Party policies towards Saudi Arabia.

Thailand

In 2007, the Green Party’s Motion 2007/08:U230 stated the following about Thailand: “Extrajudicial executions, capital punishment, systematic discrimination against ethnic minorities and migrant workers, and serious human rights abuses in the context of the conflict in southern Thailand.” Yet Swedish Arms exports to these countries involved “robots, anti-tank weapons, torpedoes and more for SEK 324 million.”

On October 18th of that year, Dagen Nyheter published an article by Torbjörn Petersson, “The Military Junta decides in favor of the Jas Gripen” (Militär juntan avgjorde till Jas Gripens fördel), which quoted then Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt as saying, “we welcome that there is an interest in the Jas Gripen as it positively influences jobs and the economy in Sweden.” A companion article by Henrik Brors, “Again a flexible interpretation of export rules” (Åter en flexibel tolkning av exportreglerna) explained that the reasons for approving sales that went against the spirit of legislation limiting such weapons was the crass interests of defense companies, the view that if Sweden didn’t sell such weapons another country would, and the need to balance for then military budget reductions (as Swedish-based defense suppliers could compensate for a decreased Swedish military budget by selling their weapons to other countries). The second item, the idea that Sweden does what another nation would not do has had limits, however. On October 29, 2007, Kittisak Siripornpitak in an article in ScandAsia explained that Royal Thai Air Force sources “suggested that Thailand was close to a deal to replace its aging F-5Es with U.S. F-16s, but the plan faltered due to U.S. rules governing the sale of military equipment to countries whose governments have been ousted in coups.”

In his article Siripornpitak writes that Reinfeldt responded to criticism of the sale by saying that the country was making “constant progress” in a movement towards establishing democracy. Reinfeldt said then, “I accept that Thailand cannot be classified as a true democracy, but rather as a nation that is moving towards democratic rule…We must not ignore this development, and we must be encouraged by its progression. We must also welcome Thailand’s interest in Swedish technology.” The pattern has been that various democracy initiatives and movements helped dull criticism of Thailand. Yet, a country that is more democratic one day, can easily be less democratic another day—particularly when militaries are empowered. These militaries have been empowered by Swedish-government-sanctioned arms exports. In fact, in March of this year, the Economist declared Thailand to be “the most improved democracy of 2022.”

This improvement was tenuous at best, short-lived at worst. Freedom House classifies Thailand as an unfree nation, noting the current regime’s use of “authoritarian tactics, including arbitrary arrests, intimidation, lèse-majesté charges, and harassment of activists.” In 2022, Amnesty International reported that rights attached “to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly came under renewed attack” in Thailand. Refugees who fled Myanmar “continued to face arrest, detention and extortion by Thai authorities.” In addition, “Malay Muslims in the southern border arena remained subject to mass and discriminatory DNA collection.” Earlier this month, The New York Times reported on the country’s general election in May. At that time, voters “dealt a crushing blow to the ruling military junta” and supported “a progressive party that challenged not only the generals but also the nation’s powerful monarchy.” In response, “the Thai military’s hold on the Senate blocked” the opposition party’s leading prime minister candidate, Pita Limjaroenrat, and “potentially” thrust Thailand “further toward autocracy.” Thailand faced what “looked like another intense period of political unrest and nationwide protests.”

In 2023, a Human Rights Watch report watch noted that in 2022 the Thai government “failed to prosecute members of its security forces responsible for torture, unlawful killings, and other abuses of ethnic Malay Muslims.” In a number of cases, “authorities provided financial compensation to victims or their families in exchange for their agreement not to speak out against the security forces, and not file criminal cases against officials.”

In May 2023, Sui-Lee Wee reported in The New York Times that Pita Limjaroenrat “promised to undo the military’s grip on Thai politics and revise a law that criminalizes criticism of the monarchy.” Wee raised questions about whether this leading opposition figure would be allowed to lead as he needed “to gather enough support in the 500-member House of Representatives to overcome a 250-member, military-appointed Senate.” Yet, Swedish engagements in Thailand have a slightly surreal quality. In February of this year, the country won the award for being the best tourist destination. In June of this year, the Bangkok Post reported that the Royal Thai Air Force planned to purchase three fighter aircraft from Swedish military contractor Saab after the US government had refused to sell Thailand F-35A fighter jets. According to one source cited by the Bangok Post, Swedish suppliers would “update a radar system” used by the Thai Air Force. Here again, Sweden may end up selling weapons to Thailand to compensate what they can’t get from another country.

On June 9, 2020, there was an announcement on Saab’s system upgrades to the Thai air force. On July 7, 2021, Saab proudly announced the tenth anniversary of its sale of Gripen fighter jets to Thailand, the company which also gave the country “a complete integrated air defence system.” Saab explains that it has been present in the country “since the mid-1980s” and supplied “Carl-Gustaf infantry weapons, Giraffe radars and RBS70 missile systems.” Saab’s Bangkok office established in 2000 was part of Thailand’s plan “to modernise its air defences.” In other words, despite the autocratic tendency in Thailand, Saab showed its solidarity with the country’s militarists.

In 2008, Hans Linde of the Left Party initiated a parliamentary inquiry about what initiatives the Swedish government intended “to take to ensure that respect for human rights and democracy is guaranteed in Thailand before a sale of the JAS Gripen to the country [was] completed?” Carl Bildt, then Foreign Minister, answered this inquiry by writing: “The Inspectorate for Strategic Products, ISP, granted permission in February 2008 for the export of the JAS Gripen to Thailand. The decision was made after hearing the Export Control Council, which consists of representatives from all [parliamentary] parties. The basis for the assessment was the parliamentary-anchored guidelines for munitions exports.” He then used human rights language to rationalize the arms sale: “In my own contacts with the interim government installed by the military after the bloodless coup of 19 September 2006, I stated that respect for human rights and a return to democracy were a necessity for our relations to return to normal. That also happened. In conclusion, I can assure that we in the government are doing what we can to ensure that human rights and the democratic system are not compromised in Thailand.”

Bildt’s wishful thinking follows a standard formula where human rights language is used to rationalize arms transfers to regimes which have proven to be instable and revert to military control. In May 2014, Thomas Fuller reported that the Swedish-supplied Thai military “seized control of the country” and also “detained at least 25 leading politicians in a culmination of months of maneuvering by the Bangkok establishment to sideline a populist movement that has won every national election since 2001.” This was “the second time in a decade that the army had overthrown an elected government.” In a major expose, investigative journalist Nils Resare cited a source who argued that the situation in the country “was embellished to the point that it became possible to approve Swedish armament exports.” A ScandAsia report published on June 2, 2014, explained that the military coup did not have any “impact on the planned delivery of Swedish Gripen fighter jets with supplies and support,” with the Thais then in possession of twelve such aircraft. The arms exports regulator, Inspectorate for Strategic Supplies, believed that the coup was not so serious as to bar supply of the aircraft. Jan-Erik Lövgren, deputy director general of the Inspectorate for Strategic Supplies, was quoted as saying about a weapons ban, “no, not right now, but we are following this closely.” In 2006, Lövgren was elected as a member of the Royal Academy of Military Sciences.

What kind of vigilance do political parties engage today in when it comes to Thailand? On their web page, the Green Party had only four references to the country, but none addressed the arms exports question. The Left Party had only one reference, which did not discuss arms exports question. So the Thailand case reveals the biggest deficit in both parties’ approach to building counter-narratives on Swedish malfeasance.

Conclusions

While both left parties oppose various forms of arms exports, the engagement appears to have diluted in terms of the force applied behind the opposition, particularly as concerns Thailand. Politicians like Hans Linde and Bodil Valero represented an authentic left anti-militarist commitment, yet Linde left the Swedish parliament in 2017 and Valero left the EU parliament in 2019. Today, both parties endorse arms transfers to Ukraine and their willingness or ability to speak out about arms exports is partially limited by media and political indifference.

The absence of specifics by left parties is underlined by the absence of any discussion about how to restructure the Swedish defense industry, support its conversion to civilian production, and de-link the Swedish military economy and foreign policy from the drive to cooperate with its American and European counterparts. This anti-militarist agenda is considered inappropriate because of the view that Russian transgressions in Ukraine threaten Western Europe and Scandinavia. This view has no substance whatsoever and is complicated by various factors including: (a) NATO’s role in initiating the conflict; (b) the fact that Western Europe did not feel its security threatened by US transgressions in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya (three episodes supported by Swedish military or defense industries), (c) Nordic involvement in military exercises near the Russian border and (d) the systemic aid which Sweden provided to Russia in the form of massive oil imports after Russia slaughtered tens of thousands in Chechnya. In 2003, Sweden even helped bomb Iraq.

When questions are raised about militarism towards the Global South, the liberal-to-left militarists will to resort to claims of whataboutism, a mind-numbing concept which attempts to link opposition to militarism with solidarity with Putin. This move is aided by Eastern European militarists who also claim that left critics of perpetuating the war in Ukraine are “Westsplaining.” This term reveals an Eastern European form of politically correct xenophobia, ironic in that many critics of NATO’s policies (such as this author) have their ancestral roots in present-day Ukraine. Solidarity with Ukraine also appears to crowd out raising other issues. This solidarity is defined by the democracy which the Swedish state aborts when it comes to the rights of Kurds bombed by Turkey, the hundreds of thousands slaughtered in Yemen or democracy champions in Thailand. Whataboutism is precisely what is called for. Those who deploy this term as an epithet are begging the question and often engaged in a militarist feelgoodism.