By Jonathan Michael Feldman, Stockholm University

February 18, 2021, Updated February 19, 2021

Just Trash All Intellectuals

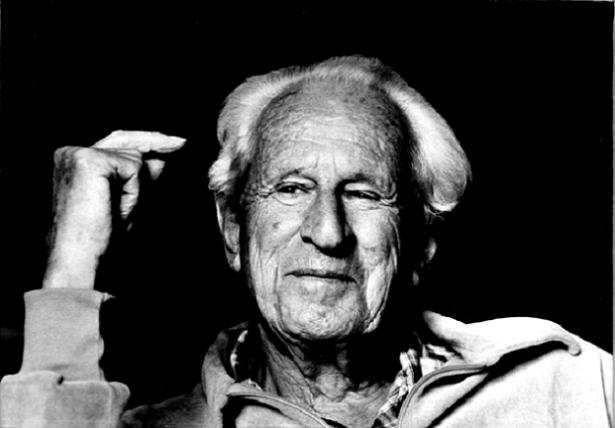

In a recent essay on Herbert Marcuse, Matt Taibbi argues the following. He recounts a professor telling him, that intellectuals as intellectuals “can justify anything.” Then he elaborates by writing that “impactful lunacy is always exclusive to intellectuals,” but that “everyone else is constrained.” He continues contempt for intellectuals by writing “an intellectual may freely mistake bullshit for Lincoln logs and spend a lifetime building palaces” and then follows with the segue “which brings us to Herbert Marcuse.” Taibbi proceeds by arguing that Marcuse is “the inspiration for a generation of furious thought-policing nitwits of the Robin DiAngelo school.” The linkage of Marcuse and DiAngelo can be found in another account which states that: “DiAngelo credits…Frankfurt School philosophers (Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse and others)…as having inspired her own work in particular and social justice education in general.” The immediate question is whether DiAngelo has properly understood Marcuse, because one could use this logic to argue that Karl Marx was an inspiration for Joseph Stalin and then argue that there are many ways in which Marx is not responsible for Stalin.

Is Guilt By Association Enough?

Taibbi does not trace through whether or not DiAngelo has given us a proper reading of Marcuse. It’s enough for him to say that she is inspired by Marcuse and leave it at that. He does go on to say that Marcuse “gave us” the ideas behind “silence equals violence,” an essay by Joy Sewing. After searching for Marcuse’s name in that essay, I found nothing. After putting her name and Marcuse’s name in Google I got two hits and in Google Scholar, this combination yielded zero hits. Taibbi continues. He says that Marcuse gave us the ideas found in the essay by Jonathan Rauch and Ray La Raja, “Too Much Democracy is Bad for Democracy,” published in The Atlantic. Marcuse’s name does not appear in that essay either. When I put the names of the authors of The Atlantic article in Google, together with “Herbert Marcuse,” I got a total of three hits only. In the more academic, Google Scholar, I got zero hits. This is hardly evidence of a strong association.

Taibbi refers to another allegedly Marcuse-inspired article called, the “Crisis of Information” published in The New York Times by Brian X. Chen. Chen does not mention Marcuse by name. When the two authors names are placed in Google this yields six hits (none of which seem relevant) and in Google Scholar zero hits. Then, we have the notorious essay “In Defense of Looting,” written by Vicky Osterweil. I proceeded to investigate whether she could be linked to Marcuse. Google Scholar yielded one hit, but Google 160. So here we might have some kind of association. Yet, in her well known interview with National Public Radio, Osterweil does not even mention Marcuse. The essay’s title has been linked, however, to 2,790 hits in Google. The first hit here is Taibbi’s essay. One of the top hits is a Tweet by James Lindsay who writes: “It’s all about using whatever tools are available to disrupt entrenched power. Very Fanon, very Marcuse.”

Lindsay is a leading debunker of the “woke,” political correct excesses of the Left. He has a three part Youtube video series on Marcuse’s essay on “Repressive Tolerance,” which he goes on to debunk at great length. Yet, when one takes Lindsay’s name and links that to Herbert Marcuse in Google Scholar one finds references to sixteen articles, none by Lindsay. So, while Lindsay pontificates at length about Marcuse, he never subjects his ideas to a peer reviewed audience. Lindsay is often mentioned by Brett Weinstein in his podcast where Taibbi has also been featured. Weinstein emphasizes the need for rigorous social science, yet we don’t see any attempt to apply such “scientific” rigor in Lindsay’s treatments of Marcuse. The right-wing Heritage Foundation has linked Lindsay’s arguments to a critique of Marcuse, however, in an essay debunking “Critical Race Theory.” I have no wish to defend this theory or necessarily fault the scavenger exercises of right-wing think tanks to expose superficial thinking by the left. Rather, I wonder what this association of Lindsay, the critique of Marcuse and right-wing think tanks really means. My hypothesis, which I don’t have space to test in this essay, is that with the stupidity of certain persons on the left, we can expect such stupid persons to misread and misappropriate persons they read. Then, this stupidity in interpretation is now being used (or recycled) by muckraking journalists (and right wing think tanks) to tarnish the persons that they misread and misappropriate. This is very similar to the logic of a witch hunt. But, guess what? It doesn’t matter because Taibbi can simply claim that “intellectuals are potential would-be idiots.”

Taibbi links Marcuse to The 1619 Project, which itself is a subject of its own controversy. I searched on the homepage of that project with the term “Herbert Marcuse,” but it yielded nothing. Mark Gonzalez, of the Heritage Foundation, does make the assumption that the two are linked, leading me to wonder if Taibbi, in search of scavenger exercises on left stupidity, is using this entity as his go-to-guy. Gonzalez wrote the following essay, “The New York Times’ 1619 Project Reeks of Herbert Marcuse’s Divisive Ideology.” In this piece, Gonzalez is upset that “Marcuse Despised and Smeared Capitalism.” Gonzalez links “Critical Race Theory” to “Critical Theory” by writing: “The critical theory Marcuse and his colleagues created has now been recast as ‘critical race theory,’ which dominates many academic disciplines, finding its way into faculties of law, English, philosophy, and more.” This is apparently a strong argument, as Google Scholar provides 775 hits linking “Herbert Marcuse” and “Critical Race Theory.” For example, in the book, Herbert Marcuse: Critical Theory as Radical Socialism, one finds the following argument: “proponents of critical race theory argue that freedom of speech is not absolute and must be viewed in the context of its real political consequences.”

Marcuse as the Anti-Democrat and Tolerance of Repression as Repressive Tolerance

Taibbi writes that “Marcuse in the 1965 essay Repressive Tolerance set out to argue that the very ‘stabilizing’ rights and freedoms that facilitated this treacherous class integration were the problem that needed conquering.” In his critique of Marcuse’s work, Taibbi quotes this passage from Marcuse: “The problem of making possible such a harmony between every individual liberty and the other, is not that of finding a compromise between competitors, or between freedom and law, between general and individual interest, common and private welfare in an established society, but of creating the society in which man is no longer enslaved by institutions which vitiate self-determination from the beginning.” In Taibbi’s analysis, he explains Marcuse as follows: “In other words, real freedom doesn’t exist in the balance between the many individual liberties doled out to persons and institutions alike in societies like ours, but only in the post-revolutionary ‘created’ society of absolute freedom as imagined by the author, a utopia Marcuse tabs the ‘pacification of existence.’ (The ostensibly antiwar leftist’s use of that term just as America was beginning its ‘pacification’ campaign in Vietnam is another of the essay’s quirks).”

Marcuse’s intention in this passage is signaled by his reference to John Stuart Mill who Marcuse writes “does not only speak of children and minors; he elaborates: ‘Liberty, as a principle, has no application to any state of things anterior to the time when mankind have become capable of being improved by free and equal discussion.’” What Marcuse seems to mean here is that authentic democracy is based not simply on democracy as a formal procedure (defined by voting), but also by critical thinking and reflective knowledge. Given democratic elections supporting politicians like Adolph Hitler, Margaret Thatcher, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and Donald J. Trump (even if malfeasance was associated with electoral victories in some cases), one might have doubts about the merits of democracy without deliberation. This point, made in an essay by the great leftist thinker Cornelius Castoriadis who elaborates upon classical Greek democracy, seems to completely elude Taibbi. Taibbi, the “journalist” takes a kind of populist, cheerleading view of democratic elections.

When Marcuse discusses “utopia,” he means a form of de-alienation which would provide complementary capacities to supplement the formal procedure of voting. Instead, Taibbi sometimes links utopia to repressive activity by citing Karl Popper who wrote, the “‘Utopian attempt to realize an ideal state… is likely to lead to a dictatorship, among other things because it contains all the same pitfalls inherent in any government.” In another essay, however, Taibbi praises the utopian idea, and says nothing about Popper. Marcuse refers to elections as “pacification” because by separating out procedural democracy from control over the economy and critical thinking, they represent a way to give citizens a false sense of control or they constitute a false sense of democracy. A strong tendency among left journalists, however, is to focus on “stolen elections” based on gerrymandering and voter suppression. These are in fact serious problems, linked to mendacious activity by Republicans. Yet, they don’t explain the various ways Democrats themselves have hoodwinked voters without voter suppression or “stolen elections” (leaving aside what John F. Kennedy may or may not have done in 1960).

Marcuse, Jacobinism and Lenin or How Taibbi Uses Popper to Trash Utopia and Marcuse

One could argue that Marcuse’s revolutionary aspirations and critique of U.S. democracy is problematic. One can argue that one should not write off democracy before a revolution takes place because of (a) the positive values of pre-revolutionary democracy and because there is much good in U.S. democracy, (b) because of the potential opportunity cost of a revolution or (c) because (a) is partially based on the American revolution itself and continuing evolution under the pressure of social movements and electoral campaigns won by progressive forces. For argument’s sake, let us assume that (b) is a problem because Jacobin or Bolshevik revolutionary efforts lend themselves to authoritarian outcomes, even if some combination of progress and regression has been associated with revolutionary movements in Latin America and elsewhere. The issue now becomes how (a) can be reconciled with a critique. One can use Marcuse to offer a critique without buying into the totality of Marcuse’s claims. Instead, Taibbi can’t make such an argument because he believes intellectuals must be forced into simplistic dualities, e.g. “quack” or not quack, intellectual or not, intellectuals ipso facto as quacks or not.

Taibbi is stuck on (b), referring to Popper who wrote: “‘Utopian attempt to realize an ideal state… is likely to lead to a dictatorship,’ among other things because it contains all the same pitfalls inherent in any government.” He continues: “Any difference of opinion between Utopian engineers must therefore lead to the use of power instead of reason, i.e. to violence.” Popper and Taibbi appear to conflate the Jacobins with anarchists and social reconstructionists who advocate utopias without violence. There have been countless utopians opposed to dictatorship such as Noam Chomsky, Paul Goodman, and Lewis Mumford. A kind of utopian formation has been operationalized in the industrial cooperatives of Mondragon in Spain (which actually survived Franco’s fascist authoritarianism and created a zone of liberation outside it). So, the conflation of all forms of “utopianism” and “authoritarianism” is totally absurd and wrong. Later, I will show how Marcuse is far from a cheerleading Leninist. Therefore, even if Taibbi only conflates utopianism with authoritarian utopians in the form taken by Jacobins and Leninists, his smearing Marcuse’s utopianism is illogical because Marcuse is hardly a cheerleading Leninist or a simple-minded Jacobin (see below).

If Taibbi believes that elections and the promise of “bourgeois democracy” (or more simply formalized electoral campaigns) are not used to rationalize the status quo, i.e. pacify people, he is sadly mistaken. Formal electoral democracy is constantly being used as a prop to narrow the idea of what democracy is vis-à-vis concentrated economic power and work places which are not democratic. While the Vietnam War was raging U.S. citizens through their votes elected Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon who prosecuted a genocidal war. In this fashion, the pacification of the vote paralleled the military pacification of the Vietnamese. American voters who reproduced the power of state managers who slaughtered people undoubtedly created some form of ire or bewilderment on the part of citizens of the Global South who must have had far less nostalgia for U.S. elections, democracy and the like than Taibbi has. This observation is not post-colonial drivel but simple common sense. The U.S. showed little remorse when they nominated John McCain as the Republican candidate for President in 2000. When I traveled to Hanoi, I saw McCain’s photograph in a war museum. McCain is viewed as a kind of war criminal there who participated in bombing missions against civilian targets in Vietnam. As John Gerassi documented in his study, the U.S. bombed hospitals, schools and other “soft targets.” In this fashion, the pacification of U.S. voters and the Vietnamese is clearly fused in the person of McCain. Yet, Taibi views Marcuse as somehow confused or simply “off” for making such association.

Taibbi appears to be involved in a Faustian bargain. He wants to deconstruct the idiotic aspects of the contemporary left and if that means ridiculing all intellectuals, he’s willing to do so. This is a rather sad development in which popular left journalists become part of the long, American as apple pie tradition of anti-intellectualism. Some left journalists, apparently worn down by what they regard as stupid drivel coming from some quarters in the university, want to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Taibbi’s Inability to Transcend His Nationalist Myopia

Taibbi gets closer to the center of the controversy around Marcuse when he quotes Marcuse as follows: “any existing rights and freedoms ‘should not be tolerated,’ because ‘they are impeding, if not destroying, the chances of creating an existence without fear and misery.’” Here we run into the question of whether Marcuse (a) condemns rights and freedoms or (b) is doing something else related to how the democratic “rights” of Americans led to “fear and misery” among Vietnamese, Nicaraguans, Guatemalans, Iraqis, Chileans, Salvadorans and countless others. Were the American citizens who voted in these war managers engaged in exemplary “rights and freedoms” or the right and freedom to trample on other peoples? Gerassi, who was my professor at Bard College (long before Taibbi arrived there), could be tossed into the heap of Third Worldist New Leftists who would trash the U.S. Or, alternatively he might better be understood as a cosmopolitan whose notion of democracy extended beyond the chauvinistic borders of the United States. Gerassi worked for the Bertrand Russell War Crimes Tribunal, headed by Jean-Paul Sartre, which declared that the U.S. had engaged in genocide in Vietnam.

Taibbi’s takedown of Marcuse continues when he writes, “settling for anything less than an absolute utopia of painlessness, or admitting any delays on the route there, even in the name of progress, is repression.” Taibbi quotes Marcuse as saying “in America, the ‘exercise of political rights (such as voting, letter-writing to the press, to Senators, etc., protest-demonstrations with a priori renunciation of counterviolence)’ only served to ‘strengthen this administration by testifying to the existence of democratic liberties.’” Taibbi summarized by writing, “in other words — drumroll — freedom is slavery.” Here Taibbi seems to suggest that U.S. voters’ freedom to propel war managers in Vietnam is not the other side of something worse than slavery, genocide.

Taibbi continues a kind of nationalistic myopia that I frankly find weird. Taibbi’s outrage continues when he calls Marcuse an Orwellian for claiming: “tolerance is intolerance” and “democracy is totalitarianism.” This part of Taibbi’s argument is strange because he seems unable to grasp the very Orwellian use of tolerance to justify intolerance and democracy as totalitarianism. Did not the tolerance of Johnson and Nixon lead to a kind of authoritarian terror on the Vietnamese people—or was that rather “democratic terror”? By problematizing “democracy” Marcuse attempts to rescue a more authentic democracy from guilt by association with its militarist variant. Did not the lack of tolerance for U.S. war criminals and militarist thugs by the anti-War movement or Vietnamese nationalists, create a kind of tolerance for the Vietnamese people? For Taibbi, these kinds of arguments are irrational and Orwellian, but the Orwellianism is on Taibbi himself who seems to stick with bourgeois tolerance and simplistic or simplified ideas about democracy.

Taibbi’s rant continues to miss the point. He writes that Marcuse “also argues progress is reaction, stability is emergency, and law is lawlessness, because ‘law and order are always and everywhere the law and order which protect the established hierarchy.’” Why isn’t the “progress” of gluttonous mass consumption with gas guzzling automobiles reaction? Why is this so hard for Taibbi to understand? Why isn’t the manipulation of law and parliaments, behind the voting for budgets to fund the slaughter in Vietnam and elsewhere, not a kind of lawlessness in the eye of the other, the ones suffering under U.S. bombs and subversion? Did any Vietnamese vote to incinerate themselves with U.S. napalm? Evidently not. Post-colonial thinkers may sometimes engage in bunk, but does that mean that gross imperialist slaughter is somehow fake news?

Taibbi faults Marcuse for suggesting that non-violence is a form of violence, “when practiced by the oppressed against the oppressor.” One can simply argue that opponents of U.S. violence who used violence to defend themselves, as in Vietnam, would view constraints on their violence as repressive tolerance of the violence done to themselves. Taibbi goes further and suggests that Marcuse is glorifying violence and links Marcuse’s ideas here to the celebration of riots as violence in the U.S. While not wishing to unpack this association, I can simply state that people who riot are probably being neglected by the democratic system and even if that’s hardly an excuse, non-violence has proven insufficient to address various long-standing grievances. As a report on The Kerner Commission of 1967 noted, this study “found one common denominator among those most likely to riot: They had experienced or witnessed an act of police brutality.” The anti-woke left might correctly argue that riots were marshalled by Republican forces to accumulate political capital. Yet, others might wonder why the causes of riots continue to fester despite the decades that have passed since the original Kerner Commission.

Does Marcuse Want to Repress Democracy or Repress Repressive Aspects of Democracy?

Taibbi faults Marcuse for favoring a kind of political repression, quoting him as writing that “extreme suspension of the right of free speech and free assembly is indeed justified only if the whole of society is in extreme danger.” This sounds reasonable until you read on: “I maintain that our society is in such an emergency situation, and that it has become the normal state of affairs.” Here we might agree with Taibbi that such a suspension of liberties and free assembly is problematic. Yet, it would be absurd to argue that free assembly and speech is never oppressive. Lynching of blacks in the United States continued up to 1964, with some databases showing lynching continuing up to 1968.

Free speech is presently associated with the promulgation of false speech, with so-called “free speech” in Facebook leading to violence. As The New York Times reported, “In Myanmar, Facebook essentially is the internet — and, by extension, the only source of information — for some 20 million people, according to [Business for Social Responsibility] estimates. Mobile phones sold there already have Facebook installed.” The 2018 Times report notes: “Facebook failed to prevent its platform from being used to ‘foment division and incite offline violence’ in the country” according to one of the company’s executives who cited “a human rights report commissioned by the company.” Here again, we have to go outside the boundaries of the United States to understand the limits of U.S.-based “free speech.” What “free speech” means is the freedom of U.S. companies to be used as tools of violence, just like U.S. arms exports are “freely traded” and used to prop up thugs throughout the Global South. A year later, another report in DW examined how “free speech” led to violence: “Fake news spread via Facebook has triggered several communal clashes resulting in deaths in Bangladesh.” Marcuse is not a quack but can be used to understand current events, where the cover of “free speech” of the Mark Zuckerberg variety directly leads people to be slaughtered. Of course, Americans can easily say, “the hell with those who would suppress free speech” even as U.S.-based multinationals (backed sometimes by left-leading civil libertarians) spread unregulated violence on innocent people in the name of glorified “free speech.” By January 6th, “the chickens came home to roost” as fake news led to violence in the Capitol building against U.S. citizens. The Anti-Defamation League, among others, drew this connection between violence and fake news. U.S. citizen civil libertarians have the luxury of praising free speech and the dangers of its suppression, yet they don’t necessarily have to pay the price of Facebook’s dystopian version of this. Tolerance of Facebook yields intolerance–a formulation that Taibbi wants to ignore or ridicule.

What are the families of the victims of people in Myamar and Bangladesh supposed to make out of Popper and Taibbi’s conceit: “A society built around individual rights and freedoms does risk allowing illiberal forces to take advantage of those freedoms.” Yes, we should take risks, but we can prevent the worst problems associated with these risks by not tolerating the extreme abuses associated with such risks? That’s essentially the core of Marcuse’s argument which is negated by bringing up an obvious platitude about taking necessary risks and mocking Marcuse.

The ridicule of Marcuse is designed to turn off part of the brain, so that complex ideas can be ridiculed and the anti-intellectuals in Taibbi’s audience can feel better about themselves. Some intellectuals may even side with Taibbi because they don’t like the Frankfurt School with which he was associated. These “likes” and “dislikes” are part of a larger social trend in which sentiment and aesthetic preferences are used to displace research, thought and critical reflection. The social media mode of being and reacting builds on a kind of consumer decadent culture which Marcuse derides, but is simplistically viewed as “elitist.” This lack of self-reflecting may be comforting for some if not many of Taibbi’s audience. To me it’s simply lazy, feelgood culture. Of course, Taibbi condemns Marcuse for not being a feelgood hedonist.

Taibbi says that Marcuse supported the “suspension of all civil rights” as “necessary.” Marcuse, however, seems more interested in suppression of the “civil rights” of oppressors as we see in contemporary debates to repress the freedom of Facebook to provoke unwarranted violence and repression. Marcuse talks about the repression of oppressive freedoms, the repression of the freedom to oppress. He is hardly calling for a martial law when he states: “It should be evident by now that the exercise of civil rights by those who don’t have them presupposes the withdrawal of civil rights from those who prevent their exercise, and that liberation of the Damned of the Earth presupposes suppression not only of their old but also of their new masters.” I believe Marcuse means that the freedoms which racist thugs use to set dogs on and club African Americans should be suspended, the same sentiments which led John F. Kennedy to federalized National Guard troops on June 10, 1963. Taibbi might be correct that Marcuse’s wording is too provocative, but as Americans say “that’s rich coming from Matt Taibbi,” the man who after all is hardly subtle when he accuses intellectuals as being more likely than not to be fraudulent quacks.

Taibbi falsely claims that Marcuse argues that the U.S. faced “an emergency so dire that a suspension of all civil liberties was warranted.” This argument is simply not in Marcuse’s essay. This claim is something Taibbi imagines, but is not really there. Marcuse says suspend the liberties of those “who prevent their exercise,” but Taibbi conflates that to mean everyone. Any democracy depends on constraints. That’s why we have police, prisons, Kennedy federalizing troops to support civil rights, arrests of January 6th insurrectionists, etc. Marcuse does write: “extreme suspension of the right of free speech and free assembly is indeed justified only if the whole of society is in extreme danger” and then he maintains “that our society is in such an emergency situation, and that it has become the normal state of affairs.” Yet, again Marcuse is pointing to a repression of anti-democratic (or perhaps criminal) elements which is the kind of repression which a strong democracy normally accepts without much fanfare. What’s become increasingly problematic is the extent to which even the criminal, anti-democratic elements are tolerated as seen in Donald J. Trump’s acquittal after his second impeachment. Taibbi does not see the relevance of Marcuse here, because he believes Marcuse is an outdated quack.

Taibbi confuses. This seems to be one of the tricks of the trade in certain forms of celebrity left journalism. You trash your opponent, salvage some of his arguments, but after doing that, you trash them again. It’s very much like toying with a person by periodically submerging them under water and then letting them come up to breath in between bouts of more drowning and trashing. Taibbi apparently acknowledges what Marcuse is after when he explains Marcuse’s thinking as follows: “While the supreme beneficiaries of this paradise of buying increase their wealth and political control, the state drops bombs abroad, and at home abuses prisoners, minorities, and the “unemployed and unemployable.” He continues to write, “I think most of us can agree that ‘radical evil’ is a term that fits many parts of the American experience, from Tuskeegee to the moonscaped hamlets of North Vietnam and Cambodia to the Covid-racked prisons of today.” Yeah, Taibbi sees but does not draw very deep conclusions from these realities.

Taibbi, however, still trashes Marcuse for writing that workers’ alienation from power is the ultimate problem. He mocks Marcuse by imagining an emergency call to the police where the operator responds asks “9-1-1, what is your emergency?” The mocking answer Taibbi attributes to Marcuse is the following: “Hi, I live in a society whose citizens choose to struggle in the market rather than enter a workless Eden of pure freedom, in which man’s vital needs will be tended to by a productive apparatus placed under the centralized control of persons like myself…” This is how Taibbi takes a sophisticated idea like the alienation of people from the control over the means of production, innovation, and corporate decision-making or even media representation and turns it into a Mickey Mouse game of utter stupidity. That’s what anti-intellectuals can do once they have dispensed with the need to have any intellectuals at all. That’s the poetic license which journalists can take after they’ve trashed the very idea of intellectuals (see above).

Taibbi demurs and writes: “People who do intellectual work should feel a responsibility to make sure the words they use at least roughly correspond to their ostensible meaning, but like a lot of German intellectuals, Marcuse had been mired in dialectical comparisons for so long that his sense of proportion was fucked beyond recognition.” I will simply say that Marcuse might have written in a less provocative or polemic style, but not everyone who appreciates philosophy would agree. I’ve already shown that Taibbi does not really understand what Marcuse is saying or concedes Marcuse’s points, e.g. about Vietnam, but then disingenuously quotes and interprets Marcuse so as to trash him. He insists that Marcuse favors autocracy.

The Lessons of Weimar: Does Cancelling Fascists and the Far Right Amount to Cancel Culture or Cancelling the Repressive Repression of Democracy?

Taibbi does not like Marcuse’s argument that “liberating tolerance, then, would mean intolerance against movements from the Right and toleration of movements from the Left.” What Taibbi leaves out was that in the previous paragraph Marcuse refers to “Fascism and Nazism” and not just any old conservative party. Taibbi can take quotes out of context because he must fulfill his prophecy that Marcuse is an idiot. Taibbi continues that “Marcuse famously believed toleration of competing views repeated the error of Weimar Germany, where ‘if democratic tolerance had been withdrawn, mankind would have had a chance of avoiding Auschwitz and a World War.’” While a generic repression of the right is clearly a bad idea, on political and moral grounds, repression of the far right or militarists engaged in repression is clearly a sound idea.

Parts of Weimar seemed to tolerate elements supporting fascism, so what is Taibbi really telling us? In Sweden, we know that Swedish military firms’ broke with Versailles restrictions, helping Germany to militarize and thus promoted a later repressive element. Does Taibbi really know what he is talking about? E. J. Gumbel was Professor of Statistics at the University of Heidelberg from 1923 to 1932. He wrote a critically important essay entitled, “Disarmament and Clandestine Rearmament Under the Weimar Republic.” Gumbel wrote: “Within the government of the Weimar Republic the army organization was decisive in organizing the illegal armament effort. Under the emperor the army had been a ‘community of its own,’ a virtual state within a state, with large budgets, tightly-knit social groups, and elaborate connections with industrial management circles. The Republic, born out of defeat, never tried to create a Republic-minded officer corps.” The Center, Democratic, and Socialist parties opposed the illegal rearmament carried out illegally by the military. Yet, German militarism opposed real democracy as “terror” became the “instrument for enforcing support for illegal armaments,” “terrorist methods were wielded against the opponents of rearmament.” In fact, the weakness of the Weimar democracy could be seen in the eventual outcome: “about four hundred political assassinations of the nationalists’ foes.”

Marcuse’s sentiments must be recognized when Gumbel writes: “the nationalist terrorists who enforced acquiescence in the rearmament of the Reich included many of the men who later became Hitler’s trusted adjutants for overseeing the mass extermination program which the Nazis carried out during the Second World War.” Gumbel, like Marcuse, links tolerance to fascism: “The Weimar Republic was killed by the great depression, which brought a revival of illegal party armies and their fight for power. When the Nazis took over, the secret armament stopped because armament became legal; the great powers had 36 accepted the Nazi breach of the Versailles Treaty. The secret armament under the Weimar Republic is a link between the defeat of 1918 and the holocaust of the Second World War” (see E. J. Gumbel, “Disarmament and Clandestine Rearmament Under the Weimar Republic,” in Seymour Melman, editor, Inspection for Disarmament, New York: Columbia University Press, 1958: 203-219).

Tolerating civil rights advocates, instead of setting dogs, hoses and clubs on them, was clearly another sound idea. Taibbi does not see it that way, because he can’t rework Marcuse’s ideas in a way that makes sense. Some muckraking journalists don’t see their job in trying to extract utility from provocative philosophical formulations, but rather their job appears to be that they must extract scandals from them. Didn’t Donald J. Trump tolerate far right wing thugs in Charlottesville and didn’t this tolerance by Trump lead to further repression by their ilk in the January 6th insurrection? Taibbi and I are living on a different intellectual planet.

People Who Work in Universities Should Shut Up About Repression

Taibbi is correct to argue that the U.S. certainly has redeemable qualities but he seems to conflate Marcuse’s status in the country or the achievements of the U.S. with an obligation to keep one’s mouth shut. As Taibbi writes: “Marcuse had no right being blind to the beauty of the American experiment, since his life was graphic proof of it. This was a man who became a wealthy international celebrity selling a book arguing that after fleeing Nazi Germany, he found ‘democratic totalitarianism’ teaching at Brandeis University.” Taibbi continues: “Rather than feel blessed to live in a country where a man can achieve wealth and fame writing one of the stupidest books in history, Marcuse became more embittered. This shines through in Repressive Tolerance, which doubles as an impassioned manifesto against enjoyment of any kind in the here and now, which Marcuse regarded as a kind of sin against the future Utopia.”

Taibbi fails to understand how Marcuse, as an exile from Nazi Germany, might have been appalled by the incineration of Vietnamese people by the U.S. government. He was supposed to think nice thoughts because he worked at a university and had a job. He was supposed to keep his mouth shut because he was a refugee and welcome his new country and all it materially gave him. Marcuse was supposed to conflate “liberation” with his material status thinks Taibbi who just can’t stomach the thought of intellectuals trashing U.S. decadence and liberty-suppressing militarism—even as Taibbi grudgingly acknowledges of U.S. militarism. Taibbi conflates an anger against genocide with persons having a psychological problem. Politically angry persons are killjoys after all. Taibbi sides with the “happy pig” over the “unhappy human” here.

Did Marcuse Love Lenin and Dictatorships?

Taibbi continues to dig up new reasons to bludgeon Marcuse: “He was the inspiration for the attitudes of modern America, which is suspicious of all forms of enjoyment divorced from political intent.” To which one could respond, Americans indulging in popular hedonistic enjoyment while contributing to the slaughter of the innocents are grounds for suspicion. Taibbi continues by superficially reading Marcuse to advocate a kind of intellectual dictatorship. He writes that Marcuse favors a “theory of an intellectual elite forced to seize absolute power on behalf of racial minorities, the disabled, and other oppressed groups, while canceling free speech and civil rights for all others, and especially for the corrupted mass of working-class people, who are no friends of the revolution but actually ignorant conservatives obstructing the road to ‘pacification and liberation.’”

It is true that Marcuse favored Leninism? Taibbi quotes Marcuse from a 1947 essay: “Marx assumed that the proletariat is driven to revolutionary action on its own, based on the knowledge of its own interests, as soon as revolutionary conditions are present. . . . [But subsequent] development has confirmed the correctness of the Leninist conception of the vanguard party as the subject of the revolution.” This statement is found in Marcuse’s essay “33 Theses.” A turn to the original manuscript reveals, however, that Marcuse did not believe that any existing Communist Party should be put in this position and he thought that such a position might be applicable elsewhere.

Taibbi does not give the full quote, because he is hunting down quotes to make Marcuse look stupid. His professional mission as I stated earlier seems to be to extract scandals from philosophical thought. Yet, he’s too eager in the hunt. So let’s go to the full quote: “The political task then would consist in reconstructing revolutionary theory within the communist parties and working for the praxis appropriate to it. The task seems impossible today. But perhaps the relative independence from Soviet dictates, which this task demands, is present as a possibility in Western Europe’s and West Germany’s communist parties” (see Herbert Marcuse, Technology, War and Fascism, London and New York: Routledge, 1998: 227). So Marcuse writes, the potential of a Leninist vanguard “seems impossible” and “perhaps” it might work when it comes to Leninism. For Taibbi these details are expendable. They’re inconvenient truths.

Things get worse after one consults one of the world’s leading theorists of Marcuse, Douglas Kellner. Kellner suggests that Marcuse is not a fan of Leninism. In his book, Herbert Marcuse and the Crisis of Marxism, Kellner writes that Marcuse “treats Soviet Marxist philosophy as a bloc and does not distinguish between the versions of Soviet Marxism developed by Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, the Left opposition and later Soviet systematizers.” In Marcuse’s book on Soviet Marxism, his “one reference to Leinin’s philosophical writings is a swipe at him” (see Douglas Kellner, Herbert Marcuse and the Crisis of Marxism, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1984: 218). In sum, Kellner thinks Marcuse is too hard on Lenin, but does illustrate how Marcuse linked Lenin to dysfunctional Soviet control.

Taibbi accused Marcuse of advocating a kind of centralized control, pointing to Marcuse’s book, One Dimensional Man, yet in his essay on “Repressive Tolerance” Marcuse clearly states “censorship of art and literature is regressive under all circumstances.” As already noted, when Marcuse discusses censorship it is applied to the kind of abuses of free speech which lead to repression. Marcuse writes: “When tolerance mainly serves the protection and preservation of a repressive society, when it serves to neutralize opposition and to render men immune against other and better forms of life, then tolerance has been perverted. And when this perversion starts in the mind of the individual, in his consciousness, his needs, when heteronomous interests occupy him before he can experience his servitude, then the efforts to counteract his dehumanization must begin at the place of entrance, there where the false consciousness takes form (or rather: is systematically formed)—it must begin with stopping the words and images which feed this consciousness. To be sure, this is censorship, even precensorship, but openly directed against the more or less hidden censorship that permeates the free media.” As for Marcuse on centralized control, in other writings Marcuse notes the advantages of decentralization as a way to elide the centralized repression of the state. When it comes to repressing oil and military production, centralized decision-making must be deployed to repress such production.

Marcuse is unfairly linked to the stupidities of the contemporary left, yet Marcuse debunked the kind of postmodern relativism which underlines such stupidities: “Within the affluent democracy, the affluent discussion prevails, and within the established framework, it is tolerant to a large extent. All points of view can be heard: the Communist and the Fascist, the Left and the Right, the white and the Negro, the crusaders for armament and for disarmament. Moreover, in endlessly dragging debates over the media, the stupid opinion is treated with the same respect as the intelligent one, the misinformed may talk as long as the informed, and propaganda rides along with education, truth with falsehood. This pure toleration of sense and nonsense is justified by the democratic argument that nobody, neither group nor individual, is in possession of the truth and capable of defining what is right and wrong, good and bad. Therefore, all contesting opinions must be submitted to ‘the people’ for its deliberation and choice.”

Did Marcuse Trash the Working Class as Agents of Change?

Taibbi catalogues several platitudes and misrepresentations of Marcuse’s work that can easily be debunked with careful research and a more thorough reading. He writes the following: “By the mid-sixties, however, [Marcuse] realized that the working-class wouldn’t do the job even if pushed. Therefore, other groups must provide the necessary revolutionary energy.” He quotes from Marcuse as follows: “Those who form the human base of the social pyramid—the outsiders and the poor, the unemployed and unemployable, the persecuted colored races, the inmates of prisons and mental institutions.” So, we often hear that Marcuse gave up on the working class and turned to students, African Americans in the ghettos and others as a new kind of proletariat.

Yet, Marcuse had other thoughts on these matters. Here I offer one last piece of evidence that maybe journalists can’t always do the apparently rubbish work of intellectuals. Marcuse in July of 1967 gave a lecture at the Free University of Berlin. There he stated: “Let me speak for just a few minutes about the prospects of the opposition. I never said that the student opposition today is by itself a revolutionary force, nor have I ever seen in the hippies the ‘heir of the proletariat’! Only the national liberation fronts of the developing countries are today in a revolutionary struggle. But even they do not by themselves constitute an effective revolutionary threat to the system of advanced capitalism. All forces of opposition today are working at preparation and only at preparation—but towards necessary preparation for a possible crisis of the system. And precisely the national liberation fronts and the ghetto rebellion contribute to this crisis, not only as military but also as political and moral opponents—the living, human negation of the system. For the preparation and eventuality of such a crisis perhaps the working class, too, can be politically radicalized” (see Herbert Marcuse, The New Left and the 1960s, London and New York: Routledge, 2005: 64). In 1969, a year later, Marcuse did not give up on the working class—a trope commonly believed even by some leftists. In An Essay on Liberation, Marcuse reflected on the Spanish Civil War and wrote about solidarity there: “in the international brigades which, with their poor weapons, withstood overwhelming technical superiority” could be found “the union of young intellectuals and workers – the union which has become the desperate goal of today’s radical opposition.”

In Conclusion

Let us sum up briefly. Taibbi finds some flaws or ambiguities in Marcuse’s writings, half acknowledges Marcuse’s existential situation as someone shocked by Vietnam, but can’t quite sympathize with someone angry or disillusioned by a U.S. society that was then relatively affluent and dropped napalm on Vietnamese and incinerated them. Marcuse is rude. Taibbi is in conflict. He knows all about Vietnam, but he does not want it to lead to a systemic critique of actually existing democracy or U.S. society. He’s part of a set of persons in the left who love America, as well they should, but can’t quite bring themselves to respect people who don’t quite love it as much as they do. Taibbi engages in selective or mendacious readings, makes some useful points that might be used to contextualize Marcuse, but it’s all lost in his journalistic hyperbole. I have nothing against journalists as my father was one. But this kind of journalism I can clearly do without. Taibbi is right about many, many things. I don’t mind his periodic trashing of left stupidities and exposure of financial mendacity and appreciate his intelligence on other topics. Yet, here he has gone too far because he seems animated by the idea that intellectuals are often just idiots. Ha ha ha, etc.