By Jonathan Michael Feldman, May 17, 2022; Updated May 22, May 24, and June 5, 2022

On Johann Karl Rodbertus, Rosa Luxemburg would write, “the stalwart Prussian prefers to crack the whip of a colonial policy of Christian ethics over the natives of the colonial countries. It is, of course, what one might expect of the ‘original founder of scientific socialism in Germany’ that he should also be a warm supporter of militarism…”

Rosa Luxemburg, The Accumulation of Capital, New York: Monthly Review Press, 1968: 247-248.

Choosing the West

In 1952, Dwight Macdonald debated the politics of East and West with Norman Mailer. Macdonald said that if he were forced to choose between the two, he would choose the West as he saw Soviet Communism and Stalinism as the world’s greatest threats. His arguments were reproduced in the book, The Responsibility of Peoples, where Macdonald stated: “I choose the West because I see the present conflict not as another struggle between basically similar imperialisms as was World War I but as a fight to the death between radically different cultures.” Of course many would prefer living in the West to the Stalinist dystopia. The problem, however, is that this choice would later mean little to the Vietnamese, Iraqis or Afghanis dodging U.S. bombs and missiles. Some victims of the East need not negate the victimizers of the West. In addition, militarism often represents a diversion of resources away from working people in the West. As Rosa Luxemburg noted in The Accumulation of Capital, “The transfer of some of the purchasing power from the working class to the state entails a proportionate decrease in consumption of means of substance by the working class.” She also noted that “the taxes extorted from the workers afford capital a new opportunity for accumulation when they are used for armament manufacture.” The militarist system was sustained by control over political and media capital: “Capital itself ultimately controls [the] automatic and rhythmic movement of militarist production through the legislature and a press whose function is to mould so-called ‘public opinion’” (page 457, 464, 466). Paul M. Sweezy later argued that militarism became the means for securing nationalism and nationalist sentiment in The Theory of Capitalist Development. In today’s terms, the national autonomy of Ukraine is being secured with the help of Western militarism.

Yet, this militarism and the dangers of a U.S. proxy war with Russia are displaced in favor of other considerations. In contemporary discourse a common approach now found in the right as well as the left is to bring up issues of secondary or tertiary importance so as to displace issues of primary importance. Here are some examples of what I call mind-numbing, the idea is that the mind should be put to sleep so that the author can get her or his point across without the reader having to think at all, i.e. the reader is being assassinated, somewhat like Roland Barthes’s idea in his essay in “the death of the author.” Barthes wrote: “In the multiplicity of writing, everything is to be disentangled nothing deciphered…the space of writing is to be ranged over, not pierced…to refuse to fix meaning is, in the end, to refuse God and ·his hypostases – reason, science, law.” In the death of the audience, the title of an essay is utilized to diminish the possibility of thinking in a way that tries to embarrass if not coerce the reader; it’s almost impossible to think differently because if the reader thinks differently, the reader will be put into an objectional category. Daniel Marwecki has similarly come to an “I choose the West moment” in his essay on the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation website entitled “We Were Wrong” (published March 11, 2022).

The Rebranding of Luxemburg’s Imperialism

While doubtful of German militarism, Marwecki seems to embrace NATO and the military and economic campaign against Russia, no matter what the costs. Rosa Luxemburg was associated with what can be called the “non-romantic” view of imperialism and militarism. In The Living Flame: The Revolutionary Passion of Rosa Luxemburg, Paul Le Blanc writes even “moderate” Social Democrats, like Eduard Bernstein of the German Social Democratic Party, had embraced various aspects of imperialism. Bernstein wrote that “to aid…the savages against advancing capitalist civilization, if it were feasible, which it is not, would only prolong the struggle, not prevent it.” Here we have classic Orientalism of the kind exposed by Edward Said. Le Blanc, in contrast, argues that it “is wrong to speculate that the Rosa Luxemburg we know would have agreed with…support of certain imperialist interventions.” Le Blanc goes further and cites George Orwell who argued that “all left-wing parties in the highly industrialized countries are at bottom a sham, because they make it their business to fight against something which they do not wish to destroy. They have internationalist aims, and at the same time they struggle to keep up a standard of life within which those aims are incompatible.” Today, we see that some on the Left would prefer what amounts to a kind of international for Ukrainian liberation led by NATO.

In 1913, Luxemburg explained that ethics of the Global North, even associated with “socialism in Germany” can also be associated with “a warm supporter of militarism.” One hundred and thirteen years later, we come to a similar finding in the person of Daniel Marwecki. Before elaborating, let us acknowledge that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has hurt the South, not to mention Ukraine itself. The Ukraine war has limited exports to Africa as Germany’s Kiel Institute for the World Economy has explained: “The country supplies large quantities of grain to North African states in particular, which other sources of supply could not replace even in the long run.”

Yet, the West’s actions have also hurt the South. Note that part of the war-related food crisis is based on sanctions against Russia. A March 20th article, “Ukraine War Threatens to Cause a Global Food Crisis,” by Jack Nicas in The New York Times states: “The war in Ukraine has delivered a shock to global energy markets. Now the planet is facing a deeper crisis: a shortage of food.” Nicas continues by writing, “Rising prices and hunger also present a potential new dimension to the world’s view of the war. Could they further fuel anger at Russia and calls for intervention? Or would frustration be targeted at the Western sanctions that are helping to trap food and fertilizer?” Nicas quotes Nooruddin Zaker Ahmadi, the director of an Afghan imports company called Bashir Navid Complex. Ahmadi shows how sanctions, seen as a solidarity move for Ukraine, are the other side of an anti-solidarity move against Afghanistan: “The United States thinks it has only sanctioned Russia and its banks…But the United States has sanctioned the whole world.”

Does Marwecki, who embraces NATO’s liberatory potential, replicate a kind of colonial ethics in the name of a militarism (tied to sanctions) that is predatory (anti-South)? Marwecki asks, “does the critique of NATO and its eastern expansion up to Russia’s borders, a critique with deep roots both within and outside of Die Linke, retain any credibility?” He answers the question that “events” have rendered the debate about such expansion “obsolete.” He seems to defend NATO because of Ukraine’s invasion and also critiques realists. Yet, Marwecki salvages NATO by showing its realist (self-help) aspects vis-à-vis Ukraine. He leaves out that NATO’s moves are part of a larger constellation of forces including militarism (arms sales, U.S. military coordination and logistical support) that limits diplomacy, sanctions that hurt states other than Russia, and the resulting costs of these moves to third parties (if not Ukraine itself).

The Whataboutism Ploy: A Formula for Saying Two Wrongs Make a Right

Some on the Left believe that solidarity with Ukraine is the ultimate litmus test of moral sanctity, displacing a Western and Saudi-led crisis in Yemen, as Yemenite victims of a brutal war become disposable casualties of “Whataboutism.” This expression is a mind-numbing idiom which is based on the following logic: If you say something bad about what the U.S. or NATO does, that does not mitigate the evils of Putin and Russia and in fact detracts from such evils. The problem with this form of mind-numbing is that “two wrongs make two wrongs (by the U.S. and Russia), not a right (by the U.S. or NATO).” Furthermore, an analysis of the arguments used to support NATO (as in NATO membership) requires an analysis of NATO and not just Russia. For the most tedious mind numbers, one will discover a kind of aesthetic and arbitrary parsing of facts that focuses on specific aspects of Russian aggression which always makes these worse than U.S. (or European equivalents). In one argument I was told that even if rape is systematic within the U.S. military, the Russians have a systematic policy of raping Ukrainians. So the debate hinges of how people are raped, rather than rape itself.

Afghanis, who some on the Left earlier rendered disposable in the name of anti-US-militarism, are now rendered disposable in the name of U.S. militarism. Here we have hyper-mind-numbing of the first order. Please note that membership in neither the Right nor the Left ideological blocs guarantee logical thinking and authentic moral frameworks. Rather, this requires something more than axiomatic thinking (something Noam Chomsky has argued in various contexts). It requires something other than what Mikael Klintman terms, “knowlege resistance.”

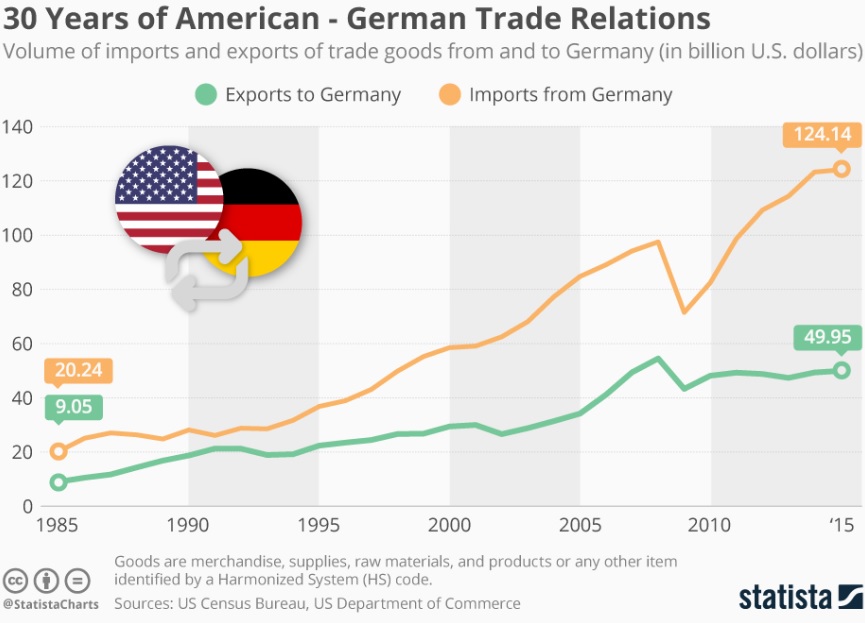

We see another dimension of Orientalism in the deconstruction of German policies to cooperate with Russia. Marwecki’s basic idea is that Germany was wrong because “Russian integration into Europe was German government policy right up to the invasion.” Marwecki asks whether “Germany simply [made] itself dependent on an autocrat as the German Green Party has alleged (and as events have now confirmed).” Here’s one problem with such arguments. Germany has similarly accommodated and empowered U.S. slaughter in Yemen (and earlier Iraq), with $86 billion worth of German imports from the United States (2021), and a similar amount of investments in U.S. government bonds ($84.3 billion in January 2022). This trade, apparently is okay, despite the 200,000 or more dead triggered by the U.S. invasion of Iraq. The Yemen war, supported by the US, was expected to lead to at least 377,000 dead by the end of 2021.

Marwecki doesn’t discuss Germany’s integration with the U.S. because that’s an inconvenient truth. Marwecki apparently believes that the Left will now revolt against what is considered politically incorrect (read Russian) globalization, but not politically correct (read U.S.) globalization. This double standard is at the heart of Cosmopolitan militarism which is a core principle of various persons in the liberal center and even parts of the “solidaristic” left. This again is an “I chose the West’s globalization” (or militarism) moment for some on the Left. As seen in Figure 1 below, Germany increased economic exchanges with the U.S. despite its bloody invasions of Iraq in 1990 and 2003.

Figure 1: Statista Data on U.S. German Trade

Denying the U.S. Role in Diplomacy, Inter-Imperialist Conflicts, Putinism and Demilitarization Sabotage

Diplomacy

Let us return to Marwecki’s argument. There’s nothing objectionable in the statement of Die Linke that this “war of aggression in contravention to international law can in no way be justified. Russia must immediately cease combat activity, agree to a ceasefire, and return to the negotiating table.” Such a statement begs the question of whether Putin would negotiate without the U.S. more actively agreeing to negotiate. Would Putin simply cease combat without an agreement by the U.S. and Western Europe to lift sanctions? A moral statement that can’t address realpolitik must suffer the moral fallout of failed diplomacy. Choosing the West does not say much when it provides an excuse for the U.S.’s failure to choose diplomacy.

I offer no apologetics for Putin’s brutal war. Yet, it’s not clear how you can negotiate with Putin and why he would take negotiation seriously if the U.S. is not involved. When Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer visited Putin and sounded somewhat pessimistic about peace talks, how could he feel optimistic when the U.S. was not involved. Nehammer did offer some positive notes, but that was repressed by certain media outlets because even such optimism was inconvenient for “the master narrative” as explained in an earlier essay.

Putin said on April 12th, that peace talks had reached a “dead end.” Why? A Truthout interview with Noam Chomsky explains: “The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is reinforcing its eastern front and there are no signs from Washington that the Biden administration is interested in engaging in constructive diplomacy to end the war in Ukraine. In fact, President Joe Biden is adding fuel to the fire by using highly inflammatory language against the Russian president.” By April 25th, David E. Sanger wrote in The New York Times that “by casting the American goal as a weakened Russian military, [Defense Secretary] Austin and others in the Biden administration are becoming more explicit about the future they see: years of continuous contest for power and influence with Moscow that in some ways resembles what President John F. Kennedy termed the ‘long twilight struggle’ of the Cold War.”

Syria

Marwecki wonders about Russia’s “pure imperialism,” something that “comes as considerably less of a surprise these days to people in Syria, Chechnya, Georgia, and many parts of Eastern Europe than to significant swathes of German society, including the German Left.” The irony here is that U.S. and NATO misdeeds in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria are contributing if not leading to the deaths of hundreds of thousands, indicate that something more than pure Russian aggression is at stake when considering the benefits of a military alliance involving the U.S. Again, all that can be incinerated through deploying the idea of “Whataboutism,” which is an abbreviation for “knowledge resistance” on the part of those using this expression. Russia’s horrible aggression and the U.S.’s horrible failure to embrace diplomacy both need to be considered (together with the U.S.’s own aggression).

The question of Syria is interesting because Russia has embraced a regime change strategy pioneered by NATO and the West. So while it is evident that Russia played a pernicious role, the logic of “whataboutism” is precisely irrelevant because Russia’s role in the Ukraine illustrates why a critical analysis of NATO and the West is needed. As Samuel Charap writes in “Russia, Syria and the Doctrine of Intervention,” Survival, Vol. 55, No. 1, 2013: “The tragedy in Syria has brought to the surface a fundamental divergence between Russia’s approach to international intervention and that of much of the rest of the international community, particularly the United States and the EU. Moscow does not believe the Security Council should be in the business of either implicitly or explicitly endorsing the removal of a sitting government. Many in the Russian foreign-policy establishment believe that the string of US-led interventions that have resulted in regime change since the end of the Cold War – Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya – is a threat to the stability of the international system and potentially to ‘regime stability’ in Russia itself and its autocratic allies in its neighbourhood. Russia did not let the Security Council give its imprimatur to these interventions, and will never do so if it suspects the stated or unstated motive is removal of a sitting government.” In Ukraine, Russia follows the earlier U.S. template.

Russia’s military engagement in Syria certainly mirrors that of the West. A Wikipedia entry on “CIA Activities in Syria,” begins as follows: “CIA activities in Syria since the agency’s inception in 1947 have included coup attempts and assassination plots, and in more recent years, extraordinary renditions, a paramilitary strike, and funding and military training of forces opposed to the current government.” An April 18, 2011 story by Ariel Zirulnic in The Christian Science Monitor explains, “Newly released WikiLeaks cables reveal that the US State Department has been secretly financing Syrian opposition groups and other opposition projects for at least five years…That aid continued going into the hands of the Syrian government opposition even after the US began its reengagement policy with Syria under President Barack Obama in 2009.” A June 21, 2012 article by Eric Schmitt in The New York Times described how the CIA was involved (or thought to be involved) in steering arms to the Syrian opposition.

If the German left offered apologetics to Russia’s militarist expansionism, we can certainly share Marwecki’s concerns. Yet, he also wants to engage in simplistic dualities. This is clear when he writes that “the war has drawn clear moral lines” and that “any attempt to understand Russian security interests — or to integrate the country into Europe, economically or otherwise — suddenly appears in Germany as naïveté at best, or as cynical, agenda-driven ignorance of the longstanding imperial plans of Putin at worst.” Yet, the longstanding imperial plans of the U.S. government go unmentioned. Apparently we have politically correct and politically incorrect imperialism.

Putinism

Of course, Russia’s attack on Ukraine involves “clear moral lines,” but so-called “Russia” is partially the West’s own creation as when the various elite interests subverted democratic developments in Russia by helping privatize public assets and facilitated the concentration of power at the expense of decentralized democracy. In the report, “Russia’s Road to Corruption: How the Clinton Administration Exported Government Instead of Free Enterprise and Failed the Russian People,” a U.S. government study published in 2000 sponsored by various members of the Congress, illustrated how “endogenous” Russian developments, partially reflected “exogenous” U.S. government failures. The report noted how a policy vacuum in the Clinton Administration related to Russia policy eventually devolved power “to a troika of subordinate officials: Vice President Gore (assisted by his foreign policy mentor Leon Fuerth), Strobe Talbott at the State Department, and Lawrence Summers at the Treasury Department.” This “Gore-Talbott-Summers troika vested authority for the development and execution of Russia policy in an elite and uniquely insular policy-making group without accountability to the normal checks and balances within the executive branch.”

The “troika” was responsible for “fundamental flaws in U.S. policy toward Russia from 1993 forward.” These included first “a strong preference for strengthening Russia’s central government, rather than deconstructing the Soviet state and building from scratch a system of free enterprise.” Second, “a close personal association with a few Russian officials, even after they became corrupt, instead of a consistent and principled approach to policy that transcended personalities.” Third, “a narrow focus on the Russian executive branch to the near exclusion of the Russian legislature, regional governments, and private organizations.” Fourth, “an arrogance toward Russia’s nascent democratic constituencies that led to attempts at democratic ends through decidedly non-democratic means.” Fifth, “an unwillingness to let facts guide policy, or even to make mid-course corrections in light of increasing corruption and mounting evidence of the failure of their policies.” While the report’s bias towards the “free market” is limited, the support for a market of activities outside the control over incumbent, elite forces was certainly warranted.

The report continued, “by focusing on strengthening the finances of the Russian government and on transforming state-owned monopolies into private monopolies, instead of building the fundamentals of a free enterprise system, the Clinton administration ensured that billions in Western economic assistance to Russia would amount to mere temporizing.” In addition, “the Clinton administration encouraged disregard for the legislative branch by the Yeltsin administration, and thus played a part in undermining the growth of pluralistic, democratic government in Russia. This has aptly been called a ‘bolshevik’ approach to accomplishing ‘reform’—authoritarian measures in both the political and economic spheres, typified by Yeltsin’s propensity to rule by decree. It virtually guaranteed that the legal reforms needed to establish a genuine free enterprise system would not be enacted in the Duma or in the regional legislatures.” These policies led to economic disaster: “The culmination of the Clinton administration’s fatally-flawed macroeconomic policy for Russia occurred in August 1998, when Russia’s default on its debts and devaluation of the ruble led to the nation’s total economic collapse. By all measurements, the disaster was worse than America’s Crash of 1929.”

Demilitarization Sabotage

Those decrying Russian militarist expansionism should understand how it has partially been rooted in failed U.S. interventions in Russia as just noted. A key question is why Russia uses that “hard power” militarist expansionist route rather than the “soft power” economic investment route. One can say that energy ties to the West were in fact this route. Yet, these investments took place against the backdrop of an enduring Russian military industrial complex, which persisted and accompanied the Russia soft power route (which itself is deconstructed as a mechanism for funding that complex). The Congressional study illustrates some important factors which have been ignored: “The failure of the Clinton administration’s economic strategy for Russia has had profound implications for Russia’s policy on proliferation of weapons and technology, and therefore for America’s national security interests.”

Russian militarist proliferation and the consolidation of the post-Soviet military industrial complex was directly linked to the failed U.S. economic interventions in Russia: “Russia’s failure to create a working free enterprise system likewise stalled conversion of the military sector of the economy. In Soviet days, the one industry in which Russia enjoyed a true comparative advantage in global markets was its military hardware, weaponry, and related technologies. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Russia inherited a massive infrastructure devoted to the development and production of weapons. Despite the 1992 beginnings of downsizing in the former Soviet military-industrial complex, much of that infrastructure remains in Russia. The decline in Russian military spending and the general failure of Russia’s economy during the Clinton-Yeltsin years meant that this immense military-industrial complex faced urgent incentives to sell as much as possible as quickly as possible, often irrespective of the long-term implications for Russia’s own security” (emphasis added). Here we see that developments in American policy helped shape the development path of Russian militarism, i.e. Russian militarism is partially exogenous and linked to past U.S. policy failures.

Putin’s abuse of its “legitimate security interests” (which did occur) does not mean that Russia did not have “security interests” in Ukraine (which of course can be displaced, i.e. ignored by a myopic focus on the abuse). All countries are concerned by what happens on their borders and whether their neighbors cooperate with an alliance ostensibly organized against them. Ukraine’s cooperation with NATO represented cooperation with such an alliance as seen in The U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership. Only through mind-numbing can such realities be denied.

Marwecki implies that militarist expansionism and “security interests” must be conflated because Putin attacked Ukraine. This belief is illogical. The counter argument is self-evident, thwarting Russia’s security interests and Western expansionism helped (or was a contributing, but not sole, factor to) trigger Russia’s militarist expansionism. This is clear in Georgia, Ukraine and Syria. In Chechnya and Syria, Russia’s brutality was self-evident, but it is unclear what lessons are supposed to be learned other than the obvious facts about the brutality of larger militarist states (where Russia and the U.S. have been in the same club). Even if Russia has an innate militaristic expansionist drive, these are no different than those in the U.S. The question then is how to create alternatives to these twin expansionisms. The answer to that question can’t be found in Marwecki’s essay as he wants to choose one militarist expansionary system over another. Even Russia’s attempts to make peaceful relations with the West are deconstructed as militarist support systems. Did the West make billions of dollars to help Russia diversify to clean energy? No. They aided and abetted a dirty industrial development there for their own selfish (vis-à-vis ecosystem requirements) needs.

Marwecki wants to pick the low hanging fruit of deconstructing Russian malfeasance, but he can’t think in reconstructionist terms. Here are some words that he does not use: “green conversion,” “disarmament,” “diplomacy,” and “multilateral.” He skillfully deconstructs Russian militarism so as to legitimate Western militarism because for him the problem is not a larger, system of competing militarisms, but rather Russia’s brutal act which is not viewed as part of a series of mutually enforcing militarisms. In Chapter 32 of The Accumulation of Capital, Luxemburg describes militarism as “a weapon in the competitive struggle between capitalist countries for areas of non-capitalist civilisation,” which today can be read to mean economic zones peripheral to those of dominant powers, e.g. areas of potential claims by Russia or the EU as is Ukraine (or perhaps a non-militarized orbit outside NATO and Russia’s grasp).

Marwecki writes that the “enthusiasm for Putin’s hyper-nationalism, militarism, and chauvinism is foreign to leftists and progressives…However, it is not without a certain irony that some leftists in both Germany and the United States occasionally sound like cold geostrategists with regard to Russia. All of a sudden, an imperial actor such as Russia is acknowledged to have security interests that deserve be taken into account. Meanwhile, Ukraine is reduced to a buffer state, a pawn of foreign powers.” I found this line of thought clever, but totally disingenuous. Can Marwecki explain how his Cosmopolitan Militarism is supposed to lead to a cease fire, diplomacy, disarmament or even arms control? Or are all these things now unfashionable, part of the guilt by association deconstruction of the old fashioned Cold War warriors, which Marwecki’s choosing the West is itself but the echo of? Marwecki wants to debunk cold geostrategists even as he has no theory about how to stop Russia or bring it to the negotiating table. The implicit message is that old fashioned arms transfers will stop Russia or deconstructing Russia as imperialist will do so. This idea would certainly sound strange to Rosa Luxemburg who saw arms transfers as old fashioned militarism. Marwecki sees Russian militarism, but ignores the West’s own militarism. He sees what Luxemburg would view as a zone beyond inter-imperialist rivalry as a “pawn” status.

The other problem with Marwecki’s analysis is that it makes demilitarization and disarmament impossible. The reason why this is so is that any mutual (or general and complete) disarmament process involves mutual cutbacks by competing military powers (as scholars like Marcus Raskin and Seymour Melman have shown). The cutbacks follow a schedule of cuts in which each competing side’s security interests are taken into consideration by negotiators and plans. Disarmament requires constraints on sovereignty, i.e. you must govern with another state or states in mind. In contrast, for Marwecki Russia can’t have security interests because to do so would be to be imperial. I suppose then that the United States can’t have security interests because it too is imperial. Therefore, if neither the Russian nor U.S. security interests can be considered, disarmament is impossible as demilitarization requires a planning process that distinguishes between real and exaggerated security interests at any given moment. In contrast, for Marwecki there are no such interests, no “surplus militarism” as I would call it, just hyper-militarism as the negation of any conception of anti-militarism.

Marwecki seems to engage in a kind of linkage of postmodern conceptions of victims to some Marxist notion of structurally determined militarism, i.e. militarism without any contingencies. He embodies an ideology of mechanistic determinism which is totally dystopian and by default leads us to choose the West’s militarism over the Russian variety of militarism. This line of thinking is now found among others on the left who are can’t think in reconstructionist terms but use the language of victims and victimizers. Thus, we have the “I choose the West’s militarism” moment.

The Critique of the Critique of NATO: Useful Idiots for NATO

Marwecki now questions the credibility of “the critique of NATO and its eastern expansion up to Russia’s borders.” He questions those who believed that an invasion of Ukraine was impossible. Such targets seem like strawmen. Key critics of NATO argued precisely the opposite, i.e. NATO expansion as a trigger to Putin’s aggressive actions. Marwecki acknowledges this argument, pointing to John Mearsheimer’s view that the Ukraine crisis is the fault of the West. Chomsky uses different language and says that that Putin and not the West is to blame for the immediate Russian invasion, but that the West (or NATO) took actions that made Russian intervention more likely. After the Russian “Ministry of Foreign Affairs shared [Mearsheimer’s] accompanying article on Twitter,” Marwecki argued that “the famous realists of yesterday are becoming the useful idiots of today.” So Mearsheimer is an idiot even though he predicted trouble, but it is the failure of not predicting trouble which concerns Marwecki. That is mind-numbing.

Marwecki makes two mistakes here. First, he assumes that anything Russia thinks is true or approves of, must be ipso facto wrong. Here the subtext is that Russia is so demonized that we can simply negate anything the Russians say or believe and achieve the truth or moral purity. Marwecki’s idea here is exceptionally dangerous and one might add, foolish. The reason for this assessment is not that we should disrespect Marwecki, but that we must also respect the dangers to Ukraine and the world from the a priori condemnation of the ability to negotiate a way out of this brutal, unjust war. In order to have diplomacy, one has to take into consideration some of the preferences of the opposing parties, even the evil and morally objectionable party (as I have suggested above). For Marwecki, we hear echoes of the ancient Cold Warriors who refused disarmament and even arms control talks with the Soviet Union. Essentially, Marwecki is to the right of even Ronald Reagan who at least favored arms control cooperation with the Russians.

The second problem with Marwecki’s line is that he is essentially a useful idiot for NATO. Marwecki claims that the debate about NATO’s eastward expansion has been “rendered obsolete by events.” This conclusion seems predicated on at least one of two fallacies. The first fallacy is that Putin’s misdeeds mean that Russia has and had no legitimate security interests. Given that Marwecki does not criticize the U.S.’s security interests, I fail to see why Russia lacks these. Others will argue that Russia’s security interests start and stop at the Russian border. This is another way of saying that Russia should or would not consider the development of an alliance of dozens of states ostensibly aimed at Russia. Even if Russia “shouldn’t,” they will, and that has consequences.

The second fallacy is that even if Russia abuses its “interests,” it is not clear that abusing these interests negates such interests. For example, some racists still had “class interests” and voted accordingly for Obama—despite being racists. The moral purity of a person or entity does not negate all interests and motivations of the person. After World War I, Germany’s interests were similarly denied and the resulting draconian peace helped contribute to a German counter-reaction, extreme nationalism, the Nazis and World War II.

Some will continue to argue that endogenous (internal) reasons explain Russia’s actions, i.e. Putin’s Russia is an aggressive, militarist imperialist state which does not need an external provocation to act. In Chechnya that might have been true, but Ukraine is not Chechnya. Clearly, NATO expansionism helped consolidate Putin’s power in Russia, even if poll data may be biased and many Russians secretly oppose the war. Endogenous (internal) reasons for invasion cannot be neatly separated from exogenous (external) reasons. Many militarist states leverage foreign threats to consolidate their own projection of militarism. Marwecki appears to understand such arguments, as when he describes realist, security dilemmas: “gains in power made by one state lead to increased insecurity for another — which then attempts in turn to expand its own power.” He explains the view of those arguing that “this security dilemma can only be managed rather than resolved” and that “to contain the threat of war, the security interests of the most powerful actors must be taken into account.” Yet, Marwecki believes Russia has no valid security interests or none relevant (or significant enough) for explaining the Ukraine War’s origins.

After spending much time alerting the reader to Putin’s malfeasance, Marwecki puts great faith in Putin’s speeches. He writes, “Vladimir Putin explained his position in two speeches where he denied Ukraine’s national independence, declaring it an artificial nation, and lied about it being ruled by ‘Nazis’ who were committing a ‘genocide’ in Donbas.” Then he reminds us that “Volodymyr Zelensky, the democratically elected president of Ukraine, is Jewish.” Marwecki tells us that the “genocide” line “is a bizarre propaganda lie to get the Russian people invested in the war.” Let us assume this to be true. If this line is but Putin’s rhetorical war motivator, then it hardly explains the exact reasons for why Putin invaded or what enticed him to invade Ukraine. After George W. Bush invented several different and changing reasons for the invasion of Iraq, we might conclude that not all of these were the true explanation. The marketing of a given reason for an intervention is hardly the same as the underlying explanation of why that intervention took place.

The Revolt in the Donbass: Russian Trigger or Endogenous Ukrainian One?

Marwecki avoids inconvenient truths. He uses Putin’s word “genocide” for describing events in Donbass but ignores other factors explaining the Donbass issue. These “other factors” are the ones ignored by both NATO and distorted by Putin’s phraseology. This is part of Marwecki’s displacement strategy: deconstruct Putin’s rhetoric, use that as a kind of strawman, but ignore the complicating factors. These factors are addressed by Renfrey Clarke in his essay, “The Donbass in 2014: Ultra-Right Threats, Working-Class Revolution, and Russian Policy Responses,” in the book Russia, Ukraine and Contemporary Imperialism, edited by Boris Kagarlitsky, Radhika Desai and Alan Freeman (Routledge, 2017 and 2019). Clarke writes of the February-April 2014 period: “As extreme Ukrainian-nationalist forces gained increasing sway over the protests in Kiev, the scepticism concerning the Maidan movement felt by Donbass residents—solidly Russian-speaking, and of diverse ethnic backgrounds—hardened into distaste and eventually, widespread militant opposition.”

Clarke continues, “On February 23, the day after Yanukovych’s ouster, the Ukrainian parliament voted to repeal a 2012 law that had allowed provinces to designate Russian as an official language. The parliament’s move was reversed on March 1 through a veto by the new acting president, Oleksandr Turchynov. But by this time, the confidence of many Donbass residents that they could co-exist with the new regime had been eroded. Alarm in the Donbass at the intentions of the new Kiev authorities increased when the government named by Prime Minister Yatsenyuk proved to include members of the fiercely anti-Russian Svoboda party, founded in the 1990s as an openly neo-Nazi organisation. Meanwhile, the new government did not conceal its plans to enact harsh neoliberal austerity policies, with steep rises in energy charges, cuts to pensions and all-round reductions in state spending.” Others like Lev Golinkin acknowledge the presence of Nazis in the Ukrainian political system, but what is interesting here is how their presence might undermine the credibility of this system to others on the path of separation.

As things evolved, the Donbass arose in a “broad political revolt,” as Clarke exaplains, but “it was unrelenting bloody-mindedness on the part of the Kiev authorities that turned the struggle into a civil war.” Here again diplomacy and the mutual recognition of security interests which Marwecki’s discourse vetoes, might have helped: “Where restraint and dialogue might have brought compromise, the Ukrainian government set its forces to staging military assaults on rebel checkpoints.” Even though “the call for regional autonomy” could be judged “reasonable,” “Yatsenyuk and his colleagues met this demand with the rhetoric of ‘anti-terrorism,’ ruling out concessions and even direct negotiation.” The protestors did not agitate for union with Russia and in a critical juncture the revolt did not even endorse formal separation from Ukraine. Eventually, as the conflict worsened, “Ukrainian forces persisted in shelling residential districts of Donbass cities.” The “broader conviction that Kiev could not be lived with came…later, nourished by Ukrainian shelling of Donbass residential districts.” Clarke explains that “the charge that the rebel ranks in the Donbass consisted mainly or largely of outsiders, particularly Russians, is plainly untrue.” Western journalists who encountered “the fighters at close hand…were forced to concede that they were overwhelmingly local people.”

This year, the International Crisis Group, published an essay explaining events related to the Donbass, “Conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas: A Visual Explainer.” They argue that “the armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine” began in 2014. The period from then to early 2022, led to the deaths of “over 14,000 people.” This war “war ruined the area’s economy and heavy industries, forced millions to relocate and turned the conflict zone into one of the world’s most mine-contaminated areas.” Zelensky’s efforts to build peace were flawed. In another essay for the International Crisis Group, Katharine Quinn-Judge argued on April 17, 2020 that these efforts were limited “by poor communication, especially with his domestic audience.” In addition, “his team has yet to offer their Russian adversaries or the Ukrainian public a coherent vision for peace – namely for how to make the controversial 2014-2015 Minsk agreements, which entail return of Donbass’s Russian-backed enclaves to Kyiv’s control, acceptable to all sides.” We see that even when Zelensky tried to address the civilian casualties, there was a backlash: “Presidential press secretary Iuliia Mendel, in line with Zelensky’s campaign pledge to treat residents of Russia-backed enclaves more like full-fledged Ukrainians, drew attention to the prevalence of civilian casualties in these areas, which she blamed on government forces’ injudicious use of return fire. This earned her a prosecutorial summons.” In other words, domestic political forces in Ukraine worked hard to sabotage diplomatic engagement. Even if Putin is responsible for attacking Ukraine, this responsibility need not displace the responsibilities of domestic Ukrainian forces for weakening the diplomatic option. Despite some peace making efforts, Quinn-Judge noted: “having come to power promising peace, Zelensky has yet to build the domestic alliances he needs to work towards it.” The Ukrainian leader was “hindered by the backlash he has faced, which has been exacerbated by his own erratic communication.”

Ukraine’s mistakes apparently include a June 2, 2014 attack on the Luhansk state administration building killing eight persons which has been linked to a Ukrainian fighter jet in reports by Radio Free Europe, CNN and the OSCE. A July 2, 2014 attack apparently by a Ukrainian jet was also linked to the death of nine civilians according to Human Rights Watch report published July 5, 2014. The author, Tanya Lokshina, wrote: “Women and men, young and old, tell us about the plane appearing in the sky close to noon on July 2, the noise, the awfulness, and worst of all, the loss of family members and neighbors. They jot down the names of the dead, including a 5-year-old boy whose legs had been torn off before he died of blood loss. He had happily celebrated his birthday with family and friends the previous day. They describe the state the bodies were in and how the walls and the fences were dripping blood. People are crying. Some have their limbs and faces scratched and burned.”

A Politics of Feelings

Marwecki seems to throw out any notion of international relations, sociology, economics, or political science because he writes: “Putin is attacking Ukraine because he feels like it.” This line of thought seems similar to Timothy Snyder’s argument that Putin is illogical and does not make decisions for what we could consider logical reasons. Let’s assume Putin is stupid or made mistakes (like Bush did in Afghanistan and Iraq). Such psychologism negates the idea that certain people have the power to be stupid or malfeasant, a power which can derive from domestic politics, historical factors or exploitation of geopolitical realities. Marwecki goes on to suggest that Trump would have “threatened [Putin] with nuclear weapons or trained his drones and special units on Putin’s head, as he did to the Iranian general Qasem Soleimani.” Given that no U.S. leader has ever assassinated a Russian one, I find this argumentation by conjecture unconvincing hyperbole—Trump, if anything, has at times been friendly to Putin and has praised him.

Marwecki claims that Russia’s security is based on its nuclear weapons and not “the neutrality of its neighbours.” Others simply argue that Ukraine has the right to do whatever it wants. If the U.S. managed to invade country after country despite having nuclear weapons, one might conclude that conceptions of security have little to do with nuclear weapons or “what states want.” One can then condemn both the U.S. and Russia for this practice and belief, but that hardly tells us how to respond to a world where these realities exist. Clearly, Ukraine’s proximity to Russia could have the former state function as a staging ground for NATO nuclear weapons or potentially insurgencies into Russia, or more likely, Ukraine could have been a staging ground for NATO troops near Russia. Whatever Ukraine might do, it nevertheless had a close relationship to NATO. In the emerging Cosmopolitan Militarism, what states think is somehow irrelevant because what’s framed as most relevant becomes the moral constructions of politicians, many so called “security experts” and opportunist politicians. I fail to see how these forces will lead us to any proactive diplomatic openings. The “I side with the West” group and those like Taras Bilous who lambast “anti-imperialist idiots” are engaged with the militarism of only one side. Bilous is correct that some leftists outside of Ukraine lack empathy for his views or Ukraine itself, now suffering from Russian imperialism. Likewise, Bilous sitting in Ukraine can’t easily see the militarism triggered by the exploitation of solidarity with Ukraine for militarist purposes, something legitimating Western imperial adventures.

A Militarist Solidarity: NATO as the Imperialist International

Marwecki argues that “the question of Western responsibility perhaps does arise” when addressing how after 2014, “a NATO membership for Ukraine was de facto off the table, as this would have brought NATO into a direct military conflict with the Russian nuclear power.” He asks “if Ukraine had no real chance of joining the alliance, couldn’t this prospect have been explicitly denied” and “couldn’t Russia have at least been offered a long moratorium for Ukrainian NATO entry?” He then continues by arguing that “the argument that NATO has outlived its purpose and should have been dissolved at the end of the Cold War now seems out of place.” Marweki apparently does not know or care about how NATO immiserated Libyans or NATO’s failures in the Kosovo conflict. The moral reference point is always Ukraine above everything else, and those who believe otherwise (like Galielo who believed that the earth revolves around the sun) must be condemned. I do not deny the extent of Russian aggression, the deaths and destruction caused. Russia must be condemned, but that need not involve erasing any nuance or deeper understanding. Sadly, nuance and facts are often the first victims of a highly polarized event, a displacement of truth which can affect elements of both the right and left. Part of the story here relates to who one’s preferred victim is in a hierarchy of victims.

Marwecki acknowledges the argument that “without NATO’s eastward expansion, there never would have been a security crisis between the West and Russia,” but then writes that “the gravity of events also suggests the opposite, equally counterfactual narrative: if Ukraine had only been accepted by NATO directly after the Cold War, Russia wouldn’t have risked war and there would be peace in Europe today.” Essentially, Marwecki sees history as being defined by two power blocs, NATO and Russia, where agency does not exist anywhere else in the system. The history of Donbass (and elaborations by Quinn-Judge) suggests mistakes by the Ukrainian state (or factions within it) which are not part of this dualism. The idea of a more comprehensive and equitable post-war security regime is similarly not part of this dualism. Marwecki’s dualism involves sanctioning either NATO malfeasance (documented in attacks on Libya and elsewhere) or Russian malfeasance (now seen clearly in Ukraine, but preceded by similar malfeasance in Chechnya and Syria).

While Marwecki engages in dualism, he soft pedals or plays that down by saying that NATO member states’ hypocrisy should be exposed and that to do “so might even be a good antidote to too much war euphoria among the spectators.” He acknowledges that “with his attempt to force a regime change in Kyiv, Putin is intentionally repeating precisely what the United States attempted in Iraq in 2003” which led to a “civil war, a failed state, and rebellion. The end result was the decline of a superpower.” The soft pedaling only goes so far because Marwecki’s default is dualism, as when he writes that “anyone who simply points out hypocrisy is arguing in bad faith” because “Putin and his ilk also like to point out the West’s crimes to justify their own.” Again, Marwecki chooses the West’s militarism because the only alternative to that in his mind is Russia’s militarism.

Marwecki returns to Russia militarism suggest that Germans misjudged Putin because they averted their “eyes and ears while Putin was dropping bombs on the civilian population in Syria to make this mistake.” To which I reply, Germany’s cooperation with the USA and NATO has represented an aversion of eyes and ears, but Marwecki writes little of that if anything. To conclude, Marwecki says that “progressive forces” do not have to “cheer on German militarization,” but “to become a credible and critical foreign policy force, the Left now also needs to change with the times.” This involves understanding the Russian threat, but apparently doing so by embracing dualisms, normalizing Germany’s integration into the NATO sphere and a one-sided narrative that will lead to either German militarism or a lack of resistance to the U.S. variety.

While one should be in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, this solidarity has lately been coupled with gross militarism and the extension of militarists’ power over the domestic population in countries like Finland and Sweden (which both rushed into NATO applications without much critical deliberation). Solidarity with Ukraine has clearly been coupled by militarism in these two countries.

One could say that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine helped trigger the move of Sweden to NATO. Yet, this is not true. Rather, militarists exploited this invasion to advance their agenda. In Sweden, the cycle began with an honest expression of solidarity with the Ukrainian people. This encouraged arms transfers to Ukraine, by the Prime Minister’s own admission. Then, a counter-reaction by Russia, involving an incursion on Swedish air space, was in turn used rhetorically to help justify an application to membership in NATO. Pleas for weapons to defend Ukraine were also linked to Russian aggression, despite U.S. aggression and the actions of states like Sweden which ramped up their investments and made billions of dollars of purchases from the Russians after that country helped slaughter thousands of Chechens. The key difference between the Chechens and Ukrainians (for NATO advocates leading Sweden) is apparently that Russia attacked a democracy in Ukraine. Yet, the very move to NATO has weakened Swedish democracy, showcasing how a one-sided campaign by some security experts, politicians and the media can create a consensus that throws out a tradition of non-formal-alignment that dates back over two hundred years. Finland, Germany and Sweden like Marwecki have chosen the West and are now even more closely identified with its militarism.