By Jonathan Michael Feldman, July 5, 2024, Updated July 6, 2024.

“In a democracy you have to face the hard, difficult issues and then go out honestly and say what you think…In the international debate because of the strength of the oil companies and other reasons, the real ecological dangers of fossil fuels are very seldom discussed…As a socialist, looking at the American scene, it’s always the fact that…the question of the ownership of the means of production and the planning of energy policy is not well in the foreground….Outside the military field….the old traditions of being against the state are so strong, you have difficulties to act.”

Olof Palme in a 1977 discussion with the actress Shirley McClaine.

Plate 1: Almedalen Entrance

The caption reads, “a place for diversity…a pace for politics.”

Overview

In this essay, I review the more than ten seminars I attended at Almedalen. I focus particularly on seminars concerning questions related to the Middle East conflict directly or indirectly. Secondarily, I examine seminars on ecological questions and democracy. While these seminars sometimes raised very interesting questions, the dominant tendency is to continually exclude the more critical approaches. The basic and repeated problem is a failure to adequately explain how one combines a moral or ethically valid point of view with power in diverse forms related to economics, politics, and media/representational capacities. The basic premise of a radical or fundamental democracy is to de-alienate the capacities of citizens, students, teachers, workers, consumers, voters, activists, etc. so they are no longer separated from diverse forms of power. Yet, the separation is maintained by various ideas related to a paternalistic state or corporate order which maintains control, surplus hierarchy, and the normality of concentrated interests. The cooperative foundations for an alternative society are rarely discussed unless they involve a cooperation without justice (where things like Koran burnings and anti-Semitism can only be addressed within certain boundaries) or cooperation under the dictates of power centralizing regimes which take the form of political democracies but really are similar to monarchal fiefdoms. In the monarchal fiefdom, a manager is the focal point and that manager’s followers usually endorse the manager’s dictates with equal measures of obsequiousness and ratification of non-critical thinking and recycling of the status quo.

Plate 2: A Seminar Celebrating Finland and Sweden’s Military Cooperation in NATO

Finnish and Swedish military men

Casting a huge shadow over this event was Sweden’s political consensus to join the U.S.-led militarist federation known as NATO. The fateful decision to join this federation has empowered militarists and their allies throughout Sweden. The right-ward drift in cultural politics, led by the Swedish Democrats, was another subtheme in this event. Their aim is to defund public culture including study circles, public media and other civil society functions or to embrace something called “Swedishness” which amounts to a nexus of ethnically white and allegedly native Swedish culture and cliches about something indigenous to Swedish society.

Plate 3: Swedish Democrat Leader and Parliament Member, Jimmie Åkesson

The Swedish Democratic leader speaks at Almedalen

The Politics of Consumption and Production: The Economic and Ecological Nexus

China and the Moral Economy

I began my tour of Almedalen events with a seminar on China, “Affärer i Kina—risker och möjligheter,” (“Business in China: Risks and Possibilities”), arranged by the National Knowledge Center on China, Business Sweden (Event ID: 70638). The participants included: Lena Sellgren, Chief Economist, Business Sweden; Joakim Abeleen, Vice President East Asia and Pacific, Business Sweden; Rémy Kolessar, Director and Section Chief for International Cooperation, Vinnova and Pia Sandvik, CEO of Teknikföretagen. The promotional description for this event reads as follows: “Surveys show that it is becoming increasingly difficult for foreign and Swedish companies to operate in China. The years of severe restrictions during the pandemic have also negatively affected foreign players’ view of the Chinese market. In addition, there are big question marks surrounding the country’s economy, partly due to an increasingly introverted and restrictive China. At the same time, the Sweden brand remains strong and China is an important market. China’s major investments, not least in technology, can offer a range of opportunities for Swedish companies. In this panel, we invite knowledgeable experts and players from the business world to discuss risks and opportunities for Swedish companies in China today.”

Sweden has extensive relations with that country even though the U.S. government increasingly wants to isolate China, the very same U.S. government that Sweden is now aligned with NATO. The seminar acknowledged the U.S.’s intensions, addressed China’s emissions. A third and fourth issue of course is China’s illegal appropriation of technology from firms which operate there and human rights concerns about Chinese actions. The seminar concluded that companies must engage in due diligence in China and support transparency.

When it comes to China there are four concerns: strategic tensions, ecocide, human rights violations and technological appropriation which Swedish business interests negotiate or displace because of capital accumulation and a drive to harvest profits by using Chinese manufacturing capacities and access to a huge market. When it comes to the human rights situation in 2023, Amnesty International reported the following: “National security continued to be used as a pretext to prevent the exercise of rights including freedoms of expression, association and assembly. Both on- and offline discussion of many topics was subject to strict censorship. Human rights defenders were among those subjected to arbitrary detention and unfair trials. The human rights situation in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region remained grave and there was no accountability for grave human rights violations committed against Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities in the region. UN experts raised new concerns that government policies and programmes were contributing to the destruction of the language and culture of ethnic groups, including Tibetans. Women’s rights activists were subjected to harassment, intimidation, arbitrary detention and unfair trials. Civic space in Hong Kong became ever more curtailed as the authorities maintained wide-ranging bans on peaceful protests and imprisoned pro-democracy activists, journalists, human rights defenders and others on national security-related charges.” These problems were not addressed at length.

The Swedish Embassy in China reports the following: “Approximately 10,000 Swedish companies conduct this trade and just over 600 Swedish or Sweden-related companies have operations in place in China. The country is Sweden’s largest trading partner in Asia.” The seminar argued that solutions are not easy. We see here that profit making and trade are used to balance against any concerns about ecocide, technological appropriation, human rights and even U.S. military preferences. The main problem, however, is that Swedish imports involve a validation of a social system of production which contradicts Sweden’s self-image as a cosmopolitan champion of democracy and freedom.

What is moral and what is legitimate can differ according to sociological (as opposed to normative) versions of legitimacy. This difference partially hinges on the logic of commerce (or capital accumulation) and its ideological polishing achieved by various displacement mechanisms. These mechanisms, similar to greenwashing, involve half measures or rhetorical critiques which are not matched by substantive actions. In a June 8, 2023 speech to the European Council of Foreign Relations, Prime Minister Ulf Kristensson expressed the dominant or hegemonic position: “The idea of de-coupling [from China] would simply not be in our interest. But as Ursula von der Leyen has rightly stated: de-risking is not de-coupling, nor does it mean disengagement. However, de-risking does mean ensuring that our exchanges with China are consistent with our interests, values and security concerns. We will continue to address human rights violations, including in Tibet, Xinjiang and Hong Kong. The same goes for the consular case of Swedish citizen Gui Minhai, which remains a priority for the new Government and the entire EU. We call for his immediate release.” Roughly translated Kristensson said that de-coupling from human rights violators is not in Sweden’s interests, but talking about human rights violations is. In other words, human rights is something that involves discursive but not material mobilizations, or mobilizations that are half-way. But while Sweden might not want to cut off trade from China entirely and doing so could contribute to a trade war, the logic of Sweden’s human rights posture is far from clear.

Greenwashing

I next attended a seminar on greenwashing, “Hur kan vi stoppa greenwashing, stärka konsumentmakten och den gröna konkurrensen?,” (“How can we stop greenwashing, strengthen consumer power and green competition?”), Event ID: 69765. The seminar rightly pointed out problems of planned obsolescence and designs that were not possible to repair. Other problems include products that were based on exaggerated green clams or products that were marked as green without necessarily being good. Consumers rank durability as being most important, followed by price, ease of recycling. The seminar addressed “a proposed new law on green claims” where “the EU is taking action to address greenwashing and protect consumers, and the environment.” The proposal would ensure “that environmental labels and claims are credible and trustworthy will allow consumers to make better-informed purchasing decisions.” By March 2024, “new EU rules to empower consumers for the green transition” entered into force. The rules meant “that before buying a product, consumers will receive better and more harmonised information on its durability and reparability.” In addition, “consumers will also be better informed about their legal guarantee rights. In addition, vague environmental claims will be forbidden, meaning that companies will no longer be able to declare that they are ‘green’ or ‘environmentally friendly’ if they cannot demonstrate that they are.” The seminar also addressed “greenhushing” which “refers to companies purposely keeping quiet about their sustainability goals, even if they are well-intentioned or plausible, for fear of being labeled greenwashers.”

Plate 4: Seminar on Greenwashing

The Greenwashing panel discussion

While these new rules promote ecological progress and consumer rights, the salient question is how consumers can gain even more control over producers to shape not merely knowledge of what is produced, but also actual productive capacities. As Seymour Melman explained in Pentagon Capitalism, the key functions of management include actual decisions about what is produced, how production is made, how much is produced and where things are produced (see Seymour Melman, Pentagon Capitalism: The Political Economy of War, New York, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1970). In essence, reforms are likely to give information rather than direct power to consumers. This approach is based on the idea that citizens are democratized consumers rather than democratized producers because the European Union has no comprehensive commitment to economic democracy. This lack of commitment is consistent with a Social Democratic model that tried to socialize consumption and not production and by the 1980s (if not earlier), accommodated itself to global outsourcing of production and globalization.

Beyond Technological Optimism

One of the most interesting seminars was organized by the think tank Norm Shift. Their seminar “Normskifte till cirkulär ekonomi–mer än teknikoptimism,” (“Norm shift to a circular economy, more than technological optimism”), Event ID: 70732, pointed to the limits of technological solutions to address the climate crisis. The panel raised the question of how norms about smoking in public places have changed in favor of greater regulation and censure. Designs can be improved to improve repairability of products. The general idea is that sticks and not just carrots are necessary to promote a green conversion and circular economy. This seminar raised many questions about the very structure of production which produces a particular kind of consumption. Complementary discussions might have investigated these issues.

First, what is the relationship between production and consumption? How does the control over or influence on production lead to a certain kind of consumption? Is leverage simply directed at what is consumed and how?

Second, what is the relationship between media power and framing (or representational power) on the structure of dystopian production that leads to dystopian consumption? Can consumer groups gain more media or representational power to influence norms, consumption patterns and producers? If so, how can they gain this power? How can one shift norms without influencing the media?

Third, what are the limits of the Swedish model which emphasized the socialization of consumption and not production? This model had involved consumer cooperatives, which more or less still exist, but placed far less emphasis on producer cooperatives such as those involved in production. One could ask how industrial cooperatives confront issues such as planned obsolescence, ecological costs, and surplus consumption and waste. In my own research, I’ve analyzed some of the answers to these questions.

Political Democracy

I attended two or more seminars on democracy. The consistent character of these seminars is that the speakers almost never define or do not even define what they mean by democracy. Rather the meaning of democracy seems to be limited to these characteristics: (a) voting, (b) participating in voluntary associations, (c) actions through non-profit organizations, study circles and civil society more generally, and (d) the agenda setting power of media and the constraining power of social media shaped by “big capital,” algorithms and knowledge resistance (although the formal explanation of that concept was nowhere described). Democratic civil society is in crisis with many groups facing financial challenges. Jan Scherman, a leading champion of the view that Swedish democracy is under threat, addressed the problem of “adaption’s tyranny,” i.e. adapting to the legitimacy of the far-right and growing constraints on democracy. One such democracy event was entitled, “Hur mår svenska demokrati och vad gör vi?” (“How is Swedish Democracy Doing and What Do We do?” (Event ID: 69439). Alternatives proposed included “solidarity,” “hunting the truth” and checking facts. The key question missing here is the democratic control over capital which extends not only to financing political engagement but also shaping a democratic culture. Another missing element is a formal discussion about how one could democratize the media and build greater media accountability. I’ve also addressed that question elsewhere.

Plate 5: Panel Discussion of Swedish Democracy

Einar Botten, Anita Goldman, Jan Scherman, Annie Lööf, Jan Eliasson, Helle Klein

Reflections on the Middle East, Israel/Palestine, the Gaza War, Anti-Semitism and Protest

I attended several seminars on relations with the Middle East, the war in Gaza or related to anti-Semitism. While (a) criticism of Israel sometimes accompanies anti-Semitism (and vice versa), sometimes (b) discussions of anti-Semitism displace criticisms of Israel. Most events and speakers at Almedalen focused on (a), with few references to (b). Another potential problem is the degree to which deconstructions or criticisms of Israel involve Hamas-washing or dilution of critiques of Hamas. This third issue is hard to measure, but involves statements about Hamas as being more than a terrorist organization without the necessary qualifications. Similar problems can emerge when addressing Israeli militarism which is diluted by ratifying Israeli statements which attribute all actions to “defensive” moves.

How far can one go to criticize Israel?

The first seminar, accessible on Youtube, “Konflikten mellan Israel och Palestina – måste jag ta ställning?,” (“The conflict between Israel and Palestine – Must I take a stand”), Event ID: 70359, involved Erik Lysén from the Swedish Church, Anna Svalander who was a local politician from Borås, and Heidi Avellan, editor at the Sydsvenskan newspaper. The seminar pointed to human rights violations on both sides, Hamas’s ties to Iran, the lack of democracy and corruption in the West Bank, the problem of settler expansion in the West Bank, the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement, and increasing polarization. This seminar dispensed with the idea that one party (Israel) was problematic and emphasized a liberal narrative that rejected the authenticity of Hamas. The panel split on the degree to which Israel was responsible for mass killing in Gaza. Lysén discussed his views on BDS actions and how they were unfairly characterized. Lysén offered the only detailed analysis of the limitations of the Israeli position. At the panel’s close, pro-Palestinian activists complained about the composition of this panel which only comprised what some refer to as “white Swedes.” There was no formal question and answer session at this panel.

Plate 6: Panel on the Israel-Palestine Conflict

Erik Lysén, Anna Svalander, and Heidi Avellan

There has been a debate on the Church’s role in the Palestine-Israel conflict or whatever term one prefers to use to describe the cycle of violence involving multiple parties in Israel/Palestine. I elaborate upon this discussion because it provides some background details on how discourse on this issue has been interpreted in a Swedish context. The details of such issues were not addressed in the seminar I attended.

On August 10, 2017, Bishop Fredrik Modéus explained that: “The Church of Sweden does not use BDS, but has chosen not to distance itself from actors who do. In the BDS movement there are of course both things that can be criticized and things that are beneficial. The Church of Sweden as such does not share the view that the methods themselves, or the goal of ending the occupation, are extremist and anti-Semitic.”

In contrast, Anika Borg, a priest and Doctor of Theology, has been critical of the church’s actions. She wrote an essay on January 19, 2022 in Dagens Nyheter about the apartheid motion passed by the Swedish Church. She argues that it involved “anti-Israel content” and “caused all the bishops, except Archbishop Antje Jackelén, to go out after the church meeting and forcefully distance themselves from it.” This “apartheid motion…caused the Jewish Central Council and other Jewish organizations to direct scathing criticism at the church’s leadership.” Borg argued that the origins of the apartheid charge against Israel “can be found during the Cold War, when the Soviet bloc together with Islamist movements sought to expand the concept of apartheid in order to denigrate democratic states.” The goal “of painting Israel as a pariah state is to freeze the country out of the world community.” Borg wrote the Church of Sweden has been engaged in “systematic collaboration with BDS” and this collaboration has “been going on for a long time.” It involves “the Kairos-Palestine network, in which the church is deeply involved” and is the BDS movement’s “ecclesiastical tool.” Since 2012 the church has disseminated a Kairos document and that has “given rise to a multitude of activities, calls for a total boycott of Israel and proclaims that Palestinian terrorism is a struggle for freedom.”

The Kairos Palestine document published in 2009, states that some Palestinians responded to the conditions they faced through “negotiations,” which was “the official position of the Palestinian Authority, but it did not advance the peace process.” In contrast, “some political parties followed the way of armed resistance.” The document continues by stating that “Israel used this as a pretext to accuse the Palestinians of being terrorists and was able to distort the real nature of the conflict, presenting it as an Israeli war against terror, rather than an Israeli occupation faced by Palestinian legal resistance aiming at ending it.” The document continues by referring to “the cycle of violence that destroys both” parties or an alternative “peace that will benefit both.” The document calls “on Israel to give up its injustice…not to twist the truth of reality of the occupation by pretending that it is a battle against terrorism.” The document argues: “The roots of ‘terrorism’ are in the human injustice committed and in the evil of the occupation. These must be removed if there be a sincere intention to remove ‘terrorism’. We call on the people of Israel to be our partners in peace and not in the cycle of interminable violence. Let us resist evil together, the evil of occupation and the infernal cycle of violence.”

Without going into details, Kairos correctly identifies a cycle of violence and the role that occupation plays in triggering something they call “terrorism” with the term placed in quotes. The identification of this cycle is certain commendable, but Kairos clearly displaces the responsibility of terrorists, terrorism, and the terror act. I’ve analyzed a more sophisticated view of these matters elsewhere. The superficiality of Kairos’s attempts at explanation should be self-evident as is the attempts to whitewash Israeli militarism and occupation. They are not self-evident of course to apologists of Hamas, Israeli militarism, and other forms of analysis that focus on one set of victims at the expense of another.

The Right-Wing and Centrist Position

Another seminar was led by the Center Mot Våldsbejakande Extremism (CVE). This panel featured Christer Mattson at the Segerstedt Institute, Catta Neuding (a program leader and producer at Axess), Petra Mårselius (who works at the Forum for Living History), Parisa Liljestrand (Cultural Minister from the Moderate Party), Isabella Pistone (based at the Segerstedt Institute) and Jona Troller from CVE. The panel was entitled, “Antisemitism – hatet som förenar extremisterna” or “Anti-Semitism—The Hate that Unites Extremists.” Mattson argued that there were three forms of anti-Semitism. The first originating in the Middle East, the second from Eastern Europe, and the third based on Christian Anti-Semitism. Mattson claimed that “anti-Semitism isn’t about Jews, but fantasies about Jews.” The seminar also argued that Israel is not committing “genocide” in Gaza. One related argument is that 50% of the deaths in Gaza are comprised of Hamas fighters (or perhaps members).

Plate 7: A Mainstream Discussion on Extremism

CVE panel discussion

Plate 8: The Mainstream View

CVE panel discussion

A BBC analysis published on February 29, 2024 cited Andreas Krieg, a senior lecturer in security studies at Kings College London, who said: “Israel takes a very broad approach to ‘Hamas membership’, which includes any affiliation with the organisation, including civil servants or administrators.” The BBC argued that they “attempted to count the number of individual claims of Hamas fighters killed on the IDF’s official Telegram channel. We found 160 posts claiming to have killed a specific number of fighters, for a total of 714 fatalities. But there were also 247 references which used terms such as ‘several’, ‘dozens’ or ‘hundreds’ killed, making a meaningful overall tally impossible. Since the beginning of the IDF incursion into Gaza, the military has accused Hamas of using the civilian population as human shields. But some experts are concerned that the IDF might be counting some non-combatants as fighters merely because they are part of the Hamas-run territory’s administration.” These details were missing in the seminar and suggested that the researchers simply used Israeli sources.

The Left-Wing Response

The third seminar, “Israel Palestina – en olöslig konflikt?,” (“Israel Palestine—an unsolvable conflict”) was organized by Lund University, Event ID 70020. The speakers included: Samir Abu Eid, a journalist at Swedish Television; Nina Gren, a lecturer at Lun University; Michael Schulz, a professor in peace and development research at Gothenburg University; and Lisa Strömbom, a lecturer in political science at Lund University. Karin Aggestam at Lund University moderated the discussion. At the outset one can argue that this seminar is where the left’s position on the Israel/Palestine question was best represented. Eid argued that Israel had moved to the right and involves cooperation with right-wing extremist parties. He discussed how Palestine was become a “non question” prior to October 7, 2023. Eid noted the rise of new settlements and outposts by occupying settlers and the problems created by normalization of the status quo, the feeling that Arab nations had given up on the Palestinian Question. The panel addressed the Nabka in which more than 400 Palestinian Arab towns and villages were depopulated by force, according to the left interpretation of these events. The majority of the Gaza population involves families that moved from the rest of Israel/Palestine.

Plate 9: Some of the panelists at Lund University’s Seminar

Lund University panel discussion

The panel addressed how the Palestinian population has become more dissatisfied with Fatah, the Palestine National Liberation Movement. One reason is corruption within this movement. A civil war with Hamas and Fatah took place in 2007, called by some “The Battle of Gaza.” This brief war took place from June 10th to 15th in 2007. In the long run, Hamas has increased in support. Both Hamas and Israel have both grown less willing to compromise, as have the populations behind these entities. There is polarization involving both sides. One tendency has been the use of the memory of the Holocaust as a mechanism to displace Israeli atrocities. This mechanism has made Israelis “blind” to the humanitarian catastrophe. There is a “symbolic struggle” going on regarding the histories of Israelis and Palestinians living in the region. A key question emerges as to “who is the aggressor and who is the victim.” Both sides of the conflict dehumanize the other. The U.S. continued to supply the Israeli military despite the catastrophe.

One panelist discussed the views of the late Johan Galtung who has addressed how culture legitimates violence. Israeli archaeologists, tied to Christian and Jewish groups, have been used as part of explorations of the “Holy Land” to promote various land claims in Palestine. An alternative cultural movement comes from Palestinians and Israelis who cooperate but are demonized by both sides. The Scholars at Risk network has been involved in addressing issues related to such cooperation. A February 8, 2024 analysis by Chandni Desai in The Conversation explained that “Gaza’s education system has suffered significantly since Israel’s” invasion. In January, Israeli forces “blew up Gaza’s last standing university, Al-Israa University.” Over a four month period, “all of parts of Gaza’s 12 universities” were “bombed and mostly destroyed.” In addition, “378 schools” were “destroyed or damaged.” According to the Palestinian Ministry of Education, “over 4,327 students, 231 teaches and 94 professors” were killed. A June 11, 2024 article published in Haaretz offered a bleak assessment of the war’s impact on Gaza’s educational institutions.

The University’s Role

Another panel, organized by Uppsala University, addressed the role of student protest against Israeli policies if not Israel itself. The panel was entitled, “Demonstrantioner eller seminarier? Om studentaktivism och demokrati vid universiteten,” (“Demostrations or seminars? On student activism and democracy at the university”), Event ID: 70513, accessible at: https://live.mediaflow.com/53CB70BVJF. The panelists included Anders Hagfeldt, head of Uppsala University; Linda Wedlin, Professor in business economic at Uppsala University; Ylva Bergström, Associate Professor in educational sociology, Uppsala University; Jimmie Kristensson, the Vice Principal (or secondary head) of Lund University; Klara Dryselius, Vice Chair of Sweden’s student union; and the moderator, Johannes Hylander.

Plate 10: Seminar on the University’s Role

Uppsala University panel discussion

Hagfeldt addressed the Kalven Report issued by the University of Chicago in 1967. The President of that university, George W. Beadle, appointed the Kalven Committee was appointed in February 1967 and they issued a report published in November 1967 entitled, “Report on the University’s Role in Political and Social Action.” Part of that report reads as follows: “The instrument of dissent and criticism is the individual faculty member or the individual student. The university is the home and sponsor of critics; it is not itself the critic. It is, to go back once again to the classic phrase, a community of scholars. To perform its mission in the society, a university must sustain an extraordinary environment of freedom of inquiry and maintain an independence from political fashions, passions, and pressures. A university, if it is to be true to its faith in intellectual inquiry, must embrace, be hospitable to, and encourage the widest diversity of views within its own community. It is a community but only for the limited, albeit great, purposes of teaching and research. It is not a club, it is not a trade association, it is not a lobby.” During protests on universities this Fall there were also seminars being given, creating a potential tension or conflict.

Hagfeldt argued that universities shouldn’t be critics, but noted that the government’s boycott of Russian Universities essentially made them act like critics, which represented a contradiction. One of the panelists referred to a book, Hålla huvudet kallt. Om distanserat engagemang i en uppjagad tid (“Keep your head cool. About distanced engagement in a busy time”) edited by Li Bennich-Björkman, Sverker Gustavsson, and Mats Lindberg. The Institute for Future Studies had earlier organized a seminar on that book accessible on their website. In an article in Dagens Nyheter, published on September 1, 2021, the researcher Johan Bjureberg argued that anger was “a feeling that gives us strength and that makes us break through obstacles, that makes resistance give way.” The article stated that: “Trying to use one’s anger to bring about important changes has meant a lot both to individuals and throughout history. An image that many remember is when Tess Asplund raised her fist against the neo-Nazis who demonstrated in Borlänge in 2016.” Another example found in that article is Greta Thunberg, “who was so angry that she shook with anger…when she visited the UN” and told “the world’s leaders with pursed lips ‘How dare you?’” Apparently, according to some researchers you should not always keep your head cool.

One panelist argued that in the United States universities are (or have been) a more central place for political organization in contrast to Sweden where study circles and other spaces have been more prominent. Another contrast noted was how Ivy League universities in the United States sit on large concentrations of capital, i.e. their endowment investments. In Sweden, universities do not control such funds. Universities in Sweden are politically steered and follow laws decided upon by politicians. Yet, a meeting of key Congresspersons during Columbia University’s protests this Fall and the funding the U.S. Government gives to universities suggests similar political leverage by the state over universities. An article in Politico published on April 25, 2024 explained this influence as follows: “GOP lawmakers, including House Speaker Mike Johnson, are demanding Education Secretary Miguel Cardona exercise powers under an anti-discrimination law to yank Columbia University’s federal cash. It’s a call echoing Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.), who has prodded several colleges since the outbreak of campus protests over the Israel-Hamas war and urged Columbia President Minouche Shafik to resign.” Nevertheless, the article noted constraints: “Being stripped of federal funding, including access to federal student aid, is one of the gravest consequences an institution can face. It first requires an investigation from the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights, which can take months, if not years, to conclude.”

Plate 11: Pro-Palestinian Group Assembles at Christian Democratic Leader’s Speech

Audience at the speech of the Christian Democratic Leader, Ebba Busch

A central question I asked the panel was to discuss the role of universities and their “free will.” While the Kalven principles suggest that the universities not be critical, Swedish universities may lack endowments and politicians may exercise ultimate political control over universities, universities still make choices. Existential philosophy teaches us that both doing something and not doing something both involve choices and such choices have normative import. This suggests the larger question of what universities can do with their resources. Swedish universities can: (a) establish think tanks and regional study centers; (b) choose banks for financial transactions—unless that is regulated by the state; (c) have internal funding which they can deploy to reward certain kinds of research or researchers; (d) organize exchange programs with specific universities; and (e) sustain or reject a kind of New Public Management tendency to promote obedient, non-critical employees (or solidify fiefdoms of managerial and teacher-affiliated power). So these choices (a) through (e) each potentially could influence a university’s policy with respect to the Gaza conflict. These choices were obliquely discussed. Being “cool” about them is not necessarily the best option, if we follow the logic proposed by Johan Bjureberg.

Plate 12: Political Archaeology of “Peace in the World” in the Garbage

Garbage bag at Almedalen

Koran Burnings

Over the last year or so, Sweden has seen multiple public events in which critics of Islam burn Korans without any direct legal repercussions. A seminar addressing Koran burning in Sweden was entitled “En Sverigebild in gungning efter koranbränninggarna?” (“An image of Sweden rocking after Koran burnings”), Event ID: 71546. Among the points made by the panel was that Iran, Iraq and Turkey make use of such burnings to gain domestic (if not foreign) policy leverage. In addition, the Swedish Democrats used such burnings to gain internal political leverage (within Sweden). Social media access amplifies the power behind these events. Some of these events can generate as many as 200,000 responses. In general, Sweden is portrayed negatively by various nations in the Middle East. One solution to this crisis might be religious diplomacy. One panelist asked “what picture do we have of ourselves?” The answer is that we don’t have a unified view of ourselves as Swedes related to such events.

Plate 13: Discussion on Koran Burnings

Henrik Fröjmark, Rouzbeh Parsi, Madeleine Sjöstedt and Erik Lysén

Rouzbeh Parsi at the Swedish Institute for International Affairs argued that Sweden can be considered as religiously illiterate. He said that it may be hard if not impossible to separate religion and politics in the Middle East. Some other questions that might be asked are the following. These three questions were not directly taken up by the discussion in an in depth fashion, although Parsi seemed to come closest to raising arguments which could then lead to such questions being asked.

First, is the individualist notion of democracy the same as a solidaristic or collective notion of democracy? In the former, individuals are free to do what they want to advance their interests. In the latter, the community’s standards might regulate action. We do see, however, how such community standards might involve apolitical, “cool heads,” but such heads are obviously not behind Koran burning, unless one argues that Koran burners are not angry but simply cool in their approach to Koran burnings that others are angry about. In other words, maybe we should be angry about Koran burnings and not coll. Our anger would embrace the anger of others about these matters such that our individualistic coolness about the burnings yields to a collective anger. What should we be angry about? These leads to two other points.

Second, one might simply ask whether a sufficient number of Sweden respect Islam and the Koran even if they don’t believe in it. Is such respect worth something? Or, rather, has Sweden long been involved in a repressive tolerance of Islamophobia and dislike for Muslims. We do have a political party that is rather large in Sweden that has normalized Islamophobia and with that normalization we see the repressive tolerance of Islamophobia. This tolerance is manifest in popular culture and elections. We should be angry about the lack of respect for Islam as a religion.

Finally, when other nations like Denmark pass laws against Koran burnings, they validate the protests against such burnings as part of a democratic response. Essentially, the law is used to repress repressive tolerance.

The Mainstream Response to Hate Speech and Discrimination

The final seminar I attended on themes related to the Middle East conflict and Gaza war fallout was entitled, “Från antisemitism och islamofobi till grannskap och sameexistens—går det?” (“From anti-Semitism and Islamophobia to neighborlyness and coexistence—does it work?”) Event ID: 71150. This panel involved the aforementioned Archbishop Martin Modéus and Christer Mattson, as well as Ute Steyer, a rabbi in Stockholm, and Kashif Virk, an imam at the Islam Ahmadiyya congregation. Felicia Ferreira, Chief Editor at Dagen newspaper was the moderator. This panel showed that neither the left, nor the center nor the right is terribly interested in Left Zionism of the sort that advocated Arab-Jewish cooperation and was against militarism and terrorism. The panel did discuss the prevalence of anti-Semitism in the Middle East and again Mattson’s belief that “Zionism is a code word for Jews.” The character of the Jewish debate on Zionism (or more accurately the form Zionism should take) was missing in action. Names like Hannah Arendt and Noam Chomsky are buried, ignored or deemed irrelevant. Hardly anything (if anything much) was said about Islamophobia. The moderator was puzzled nevertheless about the difficulties of recruiting persons to the panel representing the Muslim point of view. Virk argued against anti-Semitism, however, and for the virtues of mutual respect. Jews must be respected. When the Koran is burned, Muslims are not respected. Respect might involve anger at anti-Semites and Islamophobic persons, but not “cool heads.” Majorities might like cool heads, but minorities might not unless they learn a social code which suggests that one advances in polite society by repressing anger. Alternatively, some have the right to be angry and others don’t.

Plate 14: Discussion of Anti-Semitism

Felicia Ferreira, Christer Mattson, Martin Modéus, Kashif Virk, and Ute Steyer

This panel’s limited view is precisely what potentially feeds Swedish leftists’ views that discussions of anti-Semitism are covers for defending much of what Israel does. While anti-Semitism is a problem within Sweden (and can be found within the Swedish left or among opponents of Israel), this brand of discussion of anti-Semitism shows how easy it is to bury the far more difficult questions under the rug. The transgressions of Israel and how anti-Semites leverage them is missing. As noted earlier, legitimacy is sociological and not merely moral. The immoral but probable leverage of grievances by extremists, anti-Semites and even Islamophobic persons was not considered. That consideration is too costly for the feel good status quo. This intellectual sloppiness is sanctioned because anti-Semites are viewed as non-entities and threats who never leverage even partial truth. This failure to consider the leverage of partial truths is illogical and represents a very diluted capacity when it comes to basic social science knowledge. Yet this dilution is maintained by much of the status quo funding streams on these questions. Silence and displacement are part of the canon here. The left itself engages in silences as well with parts condoning anti-Semitism or Hamas. In this context, the mainstream plays a role in policing left stupidity, but at the cost of various sins of omission.

Cultural Politics

The Swedish Canon or NATO Cannon?

I attended two seminars on cultural politics. The first concerned plans to establish a cultural canon within Sweden or build on whatever exists on that score. The Almedalen event was entitled “Vad ska en svensk kulturkanon innehålla? Hur kan vår historia berättas?” (“What should a Swedish cultural canon contain? How can our history be explained?) Event ID: 69855, which can be accessed here: https://almedalsveckanplay.info/69855. The event involved Lars Trägårdh who led an investigation of the question and involved commentary from Anita Goldman (journalist), Lawen Redar (Social Democratic parliamentarian), and Joakim Hagerius from Equmeniakyrkan. Erik Amnå from Örebro University was the moderator.

Plate 15: Discussion of the Swedish Cultural Canon

Lars Trägårdh

A description of a similar discussion on the Accelerator webpage for an event with Trägårdh on May 29th, 2024 described the issue as follows: “The task of developing a cultural canon in Sweden has raised a number of questions about its purpose, goals and process. Some debaters have rejected the idea altogether while others have called for a list of classics or criteria for inclusion. At the same time, the initiative has generated an overwhelmingly positive interest from the public and citizens. What is at stake here? Why does it matter? Is it possible to create a canon that both reflects a set of shared ideas, values and social practices and is inclusive? How do such artistic endeavors contribute to a shared culture or ideas of citizenship and belonging? Is the idea of a common core inherently exclusionary or necessary to bind societies together? Who gets to decide? How can a broader view of culture bridge some of these tensions? How have other countries dealt with these dilemmas? We address some of these questions and more.”

At Almedalen Trägårdh argued that after World War II, there was a decline in a common national culture. He described a split or division between nationalism and multiculturalism and an underinvestment in the common. Trägårdh argued that all young persons and immigrants should gain access to the cultural capital of Swedish culture. There are divisions within Sweden creating potential gaps in feelings of security. Trägårdh saw a common Swedish culture as something established Swedes leverage at others’ expense.

Plate 16: Discussion of Sweden’s Cultural Cannon

Erik Amnå, Lars Trägårdh, Anita Goldman, Lawen Redar, Mats Berglund, Joakim Hagerius

Anita Goldman countered that there has been an attack on Swedish cultural institutions. She cited Bertolt Brecht to argue that “first comes food, then morality.” A 1990 article by Al Martinez in The Los Angeles Times explained that “Brecht was asked once what he thought about ethics.” Brecht replied, “Grub first, then ethics.” Martinez explained, “What Brecht was saying in a metaphorical sense was that survival comes before morality. You eat first, then pray for the soul of the man you just murdered for his pot roast.” Goldman noted systematic library closures, students without access to a library, a decline in popular education, and a decline in public culture.

Essentially Goldman argued that renewing such institutions was more important than the common cultural agenda of Trägårdh, although this critique raises other questions, e.g. do native or elite Swedes leverage their use of their “culture” at others’ expense, even as public support cultural institutions are eradicated? Another key question which did not seem to be addressed is what happens when the “common culture” turns rightward or embraces and tolerates the far right. What happens then? What happens when the cultural apparatus is captured by a far right agenda? Is it then worth celebrating, defending or promulgating? One assumes that this common culture refers to something far more subversive and critical or perhaps it is not as critical as it seems.

One could tune into old videos of Olof Palme on YouTube to capture part of a critical past and culture that has been steadily eroded, with substantive contributions to that erosion made by Social Democratic politicians who often have policed and edited out their own history. Examples include Social Democratic “reform” politicians who unanimously vote for spy laws that severely constrain journalism and critical dissent. Or how “reform” Social Democratic intellectuals champion NATO using arguments that have no substance whatsoever. Palme was an intellectual concerned with ecocide, a word hardly if ever heard in Almedalen. The gap between Palme and Almedalen grows more with every year, even if his presence in Visby is considered the inspiration for this event. Almedal week’s origins can be found in the speeches Olof Palme gave during several summers in the Almedalen park in Visby. The contrast between Palme’s discourse and the Almedalen event, much like the repression of anger, is just one of many contradictions one lives with. Adapting to this contradiction is part of the cultural code for social advancement and legitimacy, with sociological legitimacy thrashing moral legitimacy, with ideas of peace on the earth thrown into the garbage. In one video, Palme explains how oil is dangerous and talks about “the cancer effects of the emissions.” He says that “I can’t say that nuclear power is 100% secure, I couldn’t” even if was “more secure than the fossil fuels, at least for a transitional period.”

Plate 17: The Social Democratic Party Leader at Her Almedalen Speech

Magdalena Andersson

Lawen Redar reminded the audience that about 20% of Swedes were born out of Sweden. She noted excluded regions in the county and that language can create a common basis for society. I am not sure what all this means, however. One question that could have been asked is how potentially excluded Swedes can gain authentic representational power or how their media capital and media democracy itself could be enhanced. Such questions are rarely asked at Almedalen because I believe that many people who are speakers at this event already have sufficiently large quantities of representational power. They have such power by virtue of being politicians, military men, journalists, or business leaders. They maintain such power by filtering out contradictions.

Another assumption is that the immigrant community gets representation from elected politicians with immigrant backgrounds, who may be born in Sweden. I don’t believe that Almedalen discusses at length the idea of organic intellectuals or how immigrant background politicians may fail to represent the full interests, culture or views of “New Swedes.” Furthermore, even New Swedes who become cultural figures may themselves fail to represent those who have not made it within the system. Järvaveckan, an event held in an immigrant dense region in Stockholm which has its own political week of events, was supposed to raise the concerns of potentially excluded communities. This event is Orwellian in that it represents New Swedes as filtered through elite company patronage.

Some on the panel discussed making culture available for all as opposed to making “Swedishness” accessible. Someone raised the issue of “bourgeois” versus non-bourgeois culture and the many excluded regions in Sweden. Another question was whether a cultural canon represents a “frozen moment” which closes in culture as opposed to some more open-ended notion of freedom. Is the canon going to be forced onto immigrants? Will it consist of a set of guidelines or rules? Will it shape exclusion as opposed to inclusion? Hagerius asked whether a canon “comes from above.” Yet, what is frozen can be updated and still be used as an exclusive tool or repertoire to exclude others.

Trägårdh responded that without commonality, there will be chaos and that a Swedish culture does exist. Such a culture can be compared to a compass that you choose to give people or not. When persons have access to such a compass, this is hardly the same as an oppressive pressure applied to such persons. While we should be open to all cultures, this openness can be strengthened if we are open to what is common. Education for immigrants should involve a more sophisticated picture of the common culture. We have a common responsibility to take care of society. In sum, Trägårdh argued that can have two balls in the air at the same time, i.e. the common and the specific cultures.

Amnå responded that a common culture might involve the claims of well-established interests. Goldman brought up something about the working class background of writers, part of a them in which bourgeois culture is linked to grotesque inequality which is rationalized by donations by rich people as part of cultural patronage. A question is whether Strindberg’s contributions or that of working class culture would be so patronized. Redar questioned the state’s role in deciding a (common) culture shaped by sociological, historical and ethnographic factors. She placed great faith in the political parties as collective agents for shaping the common. Again, issues attached to the closings of cultural institutions were raised. Someone raised the issue of having a discussion about what should the common culture be.

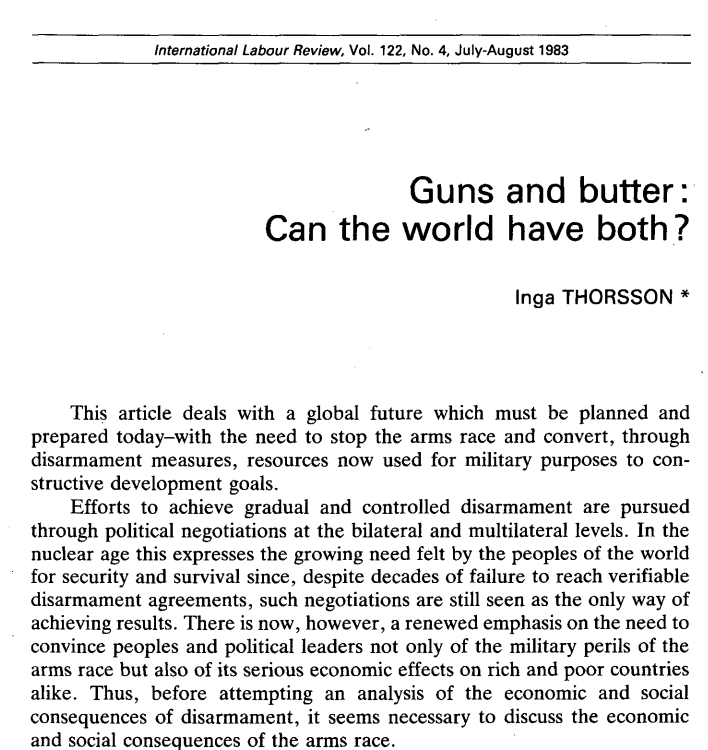

This seminar involved Trägårdh’s attempts to improve upon what is already established and his critics seeming to imply that what is established does not exist, i.e. the instrumental use of a common culture as a kind of tool or mechanism which exists independent of what the culture could or should be. This tool is used all the time and there are cultural codes which are repeatedly utilized to exclude persons. The mistake of this discussion is that a common cultural canon is a misnomer. All that is really being discussed is a set of codes, references, and ideas which are simply social, cultural and representational tools taking the form of capital. As it is, native and well educated Swedes or the cultural elite—well versed in whatever the cultural canon is or could be construed as—themselves selectively pick from Sweden’s cultural or historical past. Sweden was more than willing to throw its cultural legacy of non-alignment into the garbage to join NATO and accelerate militarism. This commitment both threatens the country’s legacies and ability to finance cultural institutions. Yet, the panel never addressed this opportunity cost and thereby engaged in a form of social amnesia vis-à-vis Sweden’s own cultural legacy of anti-militarism. The reason is that by not talking about militarism, the opportunity costs of military budgets and the sabotage thereby committed against that form of Swedish culture (embodied in Inga Thorsson), the panelists shared a knowledge of a common cultural mechanism that advances or maintains one’s status, i.e. consensus culture, Jantelagen (or the cultural code of not sticking out). In sum, the Swedish cultural canon defined by a code is what unified all panelists as well as the share social amnesia.

Plate 18: Sweden’s Lost Cultural Canon

Article by Inga Thorsson in the International Labour Review, 1983

Trägårdh reprised Todd Gitlin’s argument about the power and need for unity as an ideal of citizenship, the Commons and the related critique of multi-culturalism as relativism. Gitlin makes these arguments in The Twilight of Common Dreams: Why America is Racked by Culture Wars. Gitlin argued that left moved from common interests into particularistic ones, tied to identities. One can of course argue that a common culture of Sweden and the United States has been the embrace of militarism as culture, such that commonality itself is not an ideal. Rather, what is needed is a critical commonality rather than a non-critical commonality. Furthermore, identitarian, specialized, particular or even ethnic cultures can be co-opted to service such non-critical commonalities or even militarism. In essence, the panel might have looked to the limits not only of a common cultural cannon but also multi-culturalism itself. Yet, that was not the mission of the panel discussion, but is the limits of how the discussion was framed.

In my view, the framing of the panel discussion was topical, driven by a debate about a cultural canon, rather than a discussion of what such a canon might be when it comes to the question that concerns me most, i.e. militarism as a constraint on democracy. The discussion did not link defunding of cultural institutions to larger questions of militarism and anti-militarism. Such linkages may have moved the discourse beyond the rules of the game. These rules involve debunking hierarchy and concentrated power without naming the particular powers involved. So the whole affair and terms of the debate revealed the de facto cultural canon of Almedalen itself. Anti-militarism might be regarded as a specific or particularistic discourse having general, common advantages. So the very intellectual opposition of the particularistic against the general may be false.

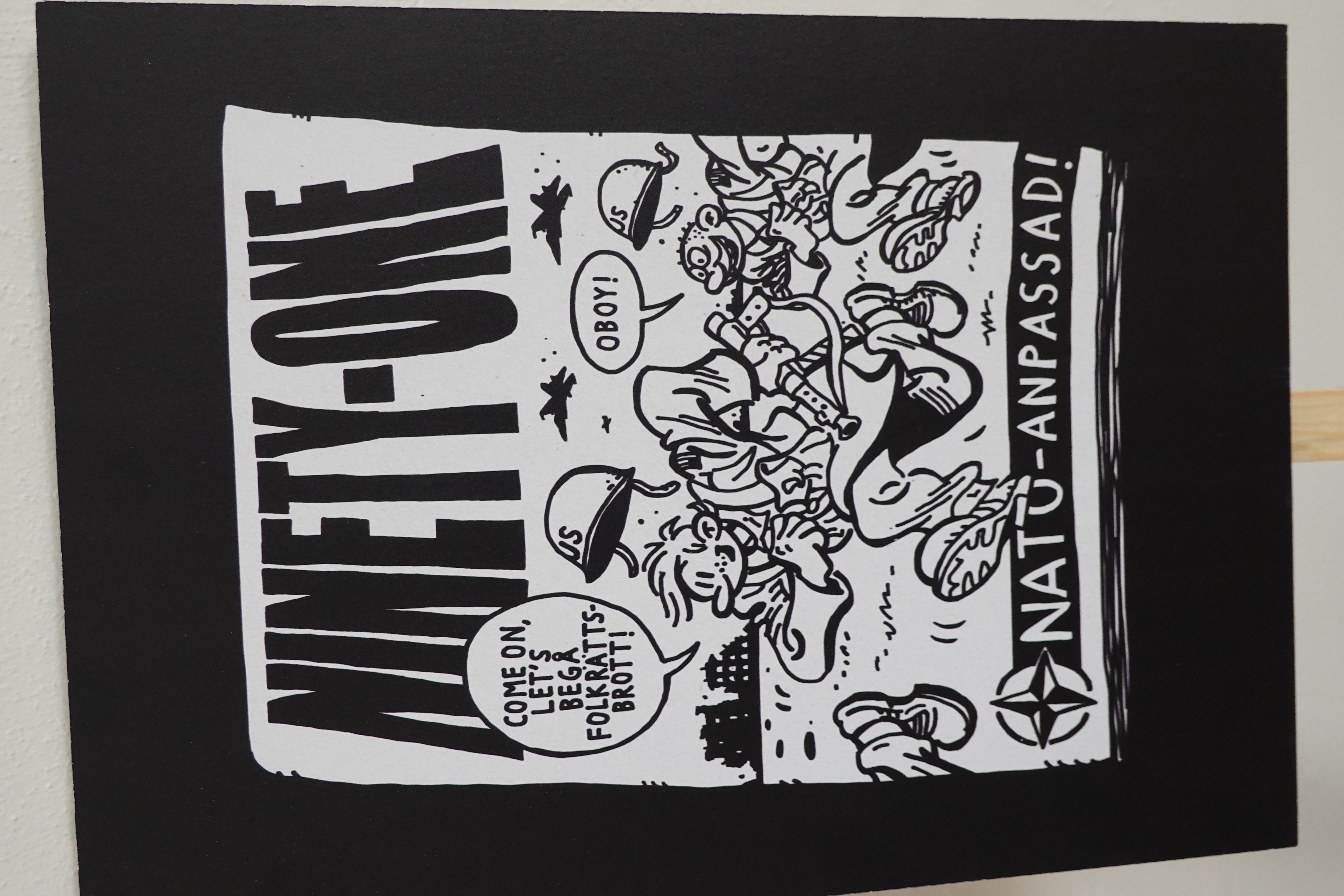

Plate 19: Anti-Militarist Propaganda at Almedalen

Poster at the public display wall of Uppsala University’s Visby campus

I am sympathetic to Trägårdh’s arguments and also some of what his critics have to say. Various cultural codes are used to regulate and control social mobility, discourse and civil society. Yet, there is another looming problem and that is whether or not the common culture as it is generally validated should be so valorized and valued beyond its instrumental value. While obvious some of the “common culture” is of value, not all such culture has value. In any case, the culture contains conflicting vales and ideas and the diversity of the common culture itself may be more important than what is common within it, e.g. the opposition of the disarmament champion Inga Thorsson to Carl Bildt the militarist pro-U.S. warfare state advocate. Such framing is considered “over the top,” irrelevant and in Swedish för mycket, i.e. “too much.” In contrast, the very intellectual fences of Almedalen are usually the problem, i.e. the questions asked are usually more important than the answers given.

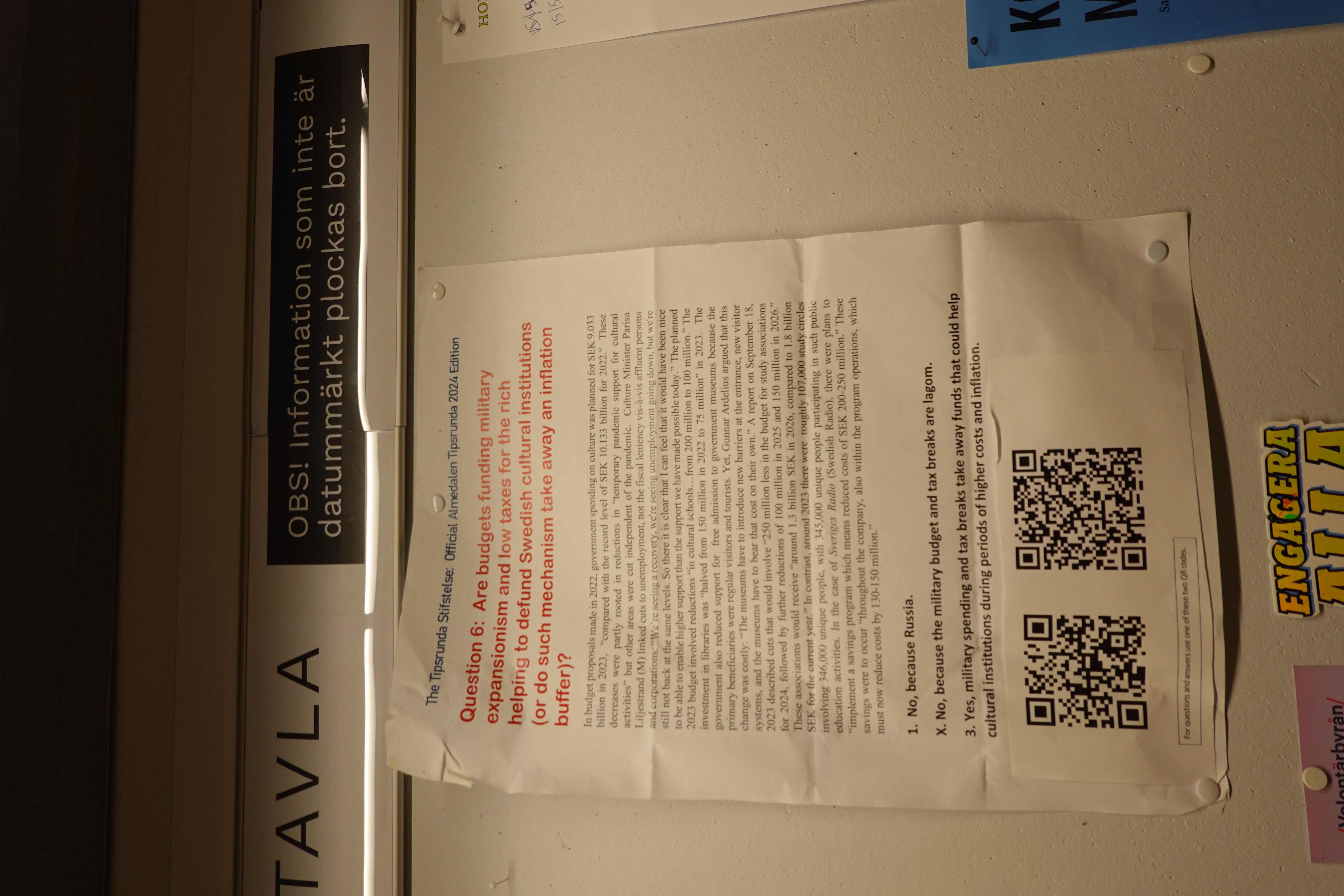

Financing Public Democracy

Another seminar specifically took up the critical question of how civil society was financed: “Vem ska finansiera civilsamhället—staten, kapitalet eller medborgaren?” (“Who should finance civil society—the state, capital or citizens?”), Event ID: 69722, accessible here: https://almedalsveckanplay.info/69722 @4:37:18). The key speakers included Charlotte Rydh, Giva Sverige; Anna Lasses, parliamentarian from the Center Party; Cecilia Engström, parliamentarian from the Christian Democrats; Jan Riise, parliamentarian from the Green Party; Alexander Christiansson, parliamentarian from the Swedish Democrats (SD); and Peter Ollén, parliamentarian frpm the Moderate Party. They were joined by Anders Årbrandt, Managing Director, of the Postkodlotteriet (a lottery financier). The SD speaker was concerned about civil society’s financing being dependent upon on the state. Among the issues discussed was whether one funding source was better than another, the stability of financing, matching funds, and the argument (made by Riise) that those with the most resources can shape outcomes. The last point suggests the need for an alternative to established, concentrated, private capital. Another argument was that politicians will steer what happens with financing and that politicians’ focus is to steer financing. Finance should be used in a good way and be subject to rules and conditions. The state only finances about a third of non-profit activity, which includes financing for unemployment.

Plate 20: Part of an Anti-War Exhibition at Almedalen

The poster reads, “come on, let’s commit violations of international law.”

The main problem with this important panel is that it offered no real discussion of ideology, agendas, and how interests and financing create a bias not just involving the government but also the private sector. Public accountability from the state was discussed as if it had no philosophical or ideological import, aside from SD’s agenda which is to reduce public financing. While citizen financing represents a third alternative, citizen financing outside of cooperative forms means something rather different than individual donations from citizens. Given that cooperatives were once an important part of Sweden’s culture, one can see how various panel discussions operate in a vacuum with respect to each other. In any case, the lost cultural canon of cooperatives is rarely addressed by anyone.