By Jonathan Michael Feldman, August 15, 2025; Updated August 23, 2025

The political discussion forum Almedalen 2025, held in Visby, Sweden, ritualized the “grand displacement”: Ecological collapse and the mass killing Gaza an increasing number call “genocide” were acknowledged, then sidelined by celebrations of missiles and markets. In Sweden’s new consensus, peace is pathological—militarism is pragmatic. Although dissenting voices were present, this article concentrates on the narratives that served powerful Swedish trends and interests.

[Det politiska diskussionsforumet Almedalen 2025, som hölls i Visby, Sverige, skådade “den stora förträngningen”: den ekologiska kollapsen och massdödandet i Gaza – som ett växande antal kallar för folkmord – erkändes, men sköts sedan åt sidan till fördel för firandet av vapenaffärer och marknadsekonomi. I Sveriges nya konsensus är fred patologiskt—militarism är pragmatiskt. Även om avvikande röster var närvarande, koncentrerar sig denna artikel på de narrativ som tjänade mäktiga svenska trender och intressen.]

Depressed Ecological Mobilization and Accelerated Military Mobilization

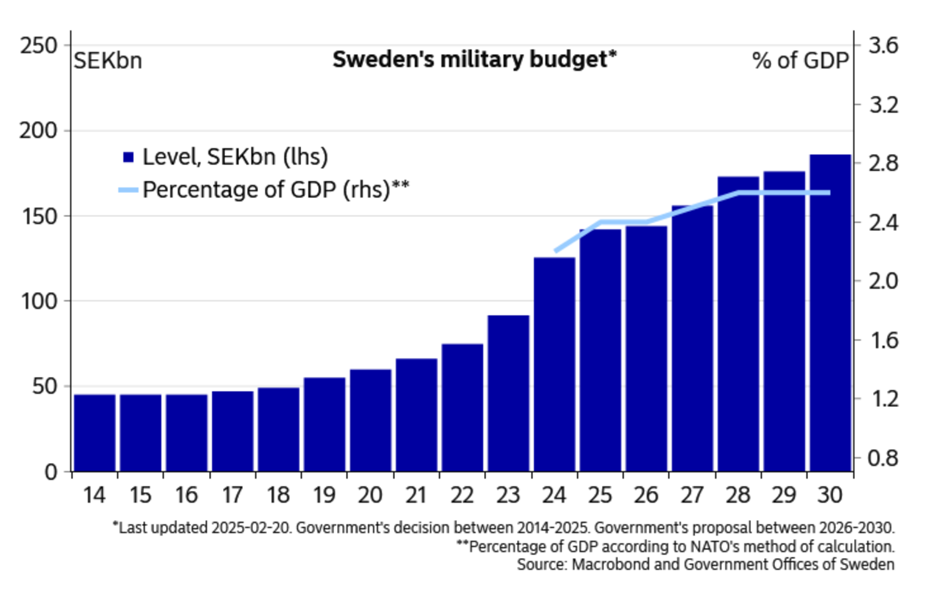

This essay examines a series of panels at Almedalen, held in Visby in June and July of this year. An earlier essay, published last year, examined Almedalen in 2024. The analysis provided here is not what you would expect to find among most political scientists, security analysts or economists. The backdrop to my framing this year is a deterioration of Sweden’s ecological capacities as documented in February 2023, September 2024, and March 2025 and a massive military budget increase (see Figure 1). So while Sweden—like other nations in Europe—engaged in a military mobilization, several looming ecological crises suggested that an ecological mobilization was the priority. On the European front, the Financial Times announced earlier this month that Europe was “undergoing a historic surge in military production, with arms factories expanding at three times the typical peacetime rate.” Using radar satellite data, they revealed “more than 7 million square meters of new industrial development dedicated to weapons manufacturing across the continent.”

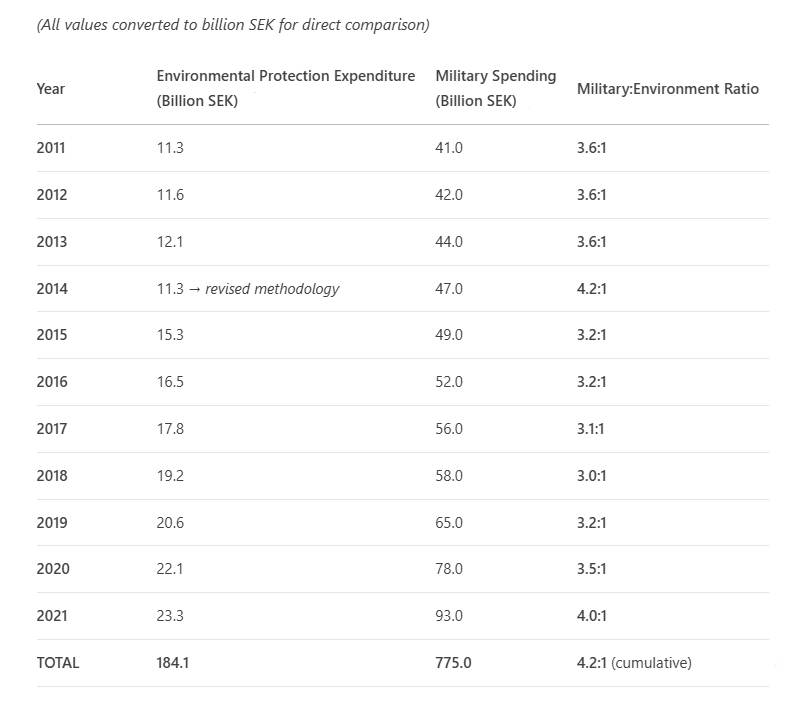

The counterargument that Russia invaded Ukraine is insufficient because NATO expansion encouraged the Russian invasion and because Europe’s diplomatic efforts have been weak, demonizing even discussions with Putin. The Conflict and Environment Observatory concluded in a May 2025 paper, “How increasing global military expenditure threatens SDG 13 on Climate action,” preceding Almedalen: “the global increase in military expenditure has clear negative implications for achieving the targets of SDG 13: climate action. Furthermore, this current drive for rearmament only builds on the existing impact that militarism has had on global emissions for decades.” A relatively clear comparison of these budgetary tradeoffs appears in Figure 2. Counterfactual arguments—that money not spent on the military would not necessarily be allocated to green initiatives—beg the question of how military investments subsidize institutions that promote militarism. This, in turn, comes at the expense of an advanced ecological agenda. This essay explains some details of this counter-argument about the absence of a linkage.

Figure 1: The Military Budget Escalation in Sweden

Source: Joel Lundh, “Sweden: Growing defence budget,” Nordea, February 27, 2025. Accessible at: https://corporate.nordea.com/article/97663/sweden-growing-defence-budget

Figure 2: Sweden’s Environment Versus Ecological Spending: 2011-2021

Sources and methodological note: The table comparing Sweden’s military and environmental spending from 2011 to 2021 uses exclusively Swedish krona (SEK) data from two official sources accessed through Statista. Military expenditure figures come from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) via their Statista dataset, which reports Swedish Ministry of Defence budgets covering personnel, operations, and equipment procurement, while excluding veterans’ benefits and paramilitary forces. Environmental protection expenditure data originates from Statistics Sweden’s reporting to Statista, following the EU’s CEPA classification that includes waste management, water protection, biodiversity conservation, and pollution control from both public and private sectors. All values were standardized to billion SEK, with original environmental data (reported in million SEK) converted by dividing by 1,000. Notably, the environmental data reflects a methodology revision in 2014 that caused a temporary dip in reported spending that year. The complete dataset is available at these Statista links: Military Spending 2010-2023 and Environmental Expenditure 2011-2021. This comparison table was compiled by the author on August 15, 2025, using exclusively these primary sources without AI-generated estimates or modifications to original methodologies. The table was generated by deepseek on this date.

This essay argues that Sweden’s policy elite has institutionalized a doctrine of “neoliberal militarism”—prioritizing military expansion and global market integration while displacing ecological action, Gaza accountability, and economic democracy. Almedalen 2025 reveals how this consensus silences alternatives through curated “dialogue” that avoids much substantive contestation. Neoliberal militarism operates via a self-reinforcing circuit: Military contracts boost corporate profits (SAAB, BAE Systems) → Profits fund lobbying for expanded defense budgets → Militarized foreign policy (e.g., Gaza non-intervention) justifies security rhetoric → Security rhetoric legitimizes austerity for social/ecological programs. For a definition of “Neoliberalism” as used in this essay, see Note 1 below.[1]

In this essay, I adopt an encyclopedic approach for three reasons. First, details matter—the way arguments are made is often as revealing as their content. Second, I want to preserve a historical record of elite discourse in 2025, shaped by multiple crises. Third, brevity would force reliance on my own interpretation; by providing fuller accounts, I enable readers to draw their own conclusions alongside mine. Finally, I am working on a separate essay on the Gaza crisis and what to do about it, but hints of my thinking certainly appear in this essay.

The Gaza Test

There is also a humanitarian and militarist crisis in Gaza related to mass killing (over 60,000 and counting), expanding famine and an authoritarian movement in Israel proper. These crises demand that Swedish civil society act to end suffering and promote an equitable resolution of the Palestine-Israel conflict. The question becomes whether the quality of the discourse in civil society is up to addressing these crises. This quality informs whether, how and the extent to which intermediary organizations and institutions can address contradictions in a meaningful way.

By the start of Almedalen on June 23, 2025, the Palestinian death toll in Gaza was likely in the range of 55,000-57,000 people based on data compiled by Statista. By August the total deaths reached over 61,000. The Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that as of 22 June 2025, 50 hostages were “still being held in captivity in Gaza” with 49 abducted on October 7th and one hostage (Hadar Goldin) who had been held in Gaza since 2014. There were eleven events on Gaza and a march in Visby in support of Palestinians there. A review of panels using the word “Gaza” at Almedalen as well as my impression of various talks I did attend suggest that there was no coherent focus on how to change Swedish policy to create a needed accountability system in this conflict, i.e. mechanisms to leverage state power to end the conflict.

One panel entitled, “Hur stadigt står svensk demokrati?” (“How stable is Swedish democracy?”). The panel was described by the official Almedalen program as follows: “Almedalen Week begins in the shadow of the major NATO summit, the war in Gaza and Donald Trump’s constant rhetoric. What is Sweden’s role in a turbulent world and are there signs that democracy is under threat here too?” The two participants were Annie Lööf, the former Center Party leader and Anette Holmqvist, a political reporter at Expressen. At the panel, the erosion of democratic states in the world was discussed as well as the dangers of the far right. Lööf argued that the US has moved further along the path of an authoritarian path during the Trump Administration. By 17 minutes and 19 seconds into the recorded version of the discussion, Lööf described events in Gaza as a “brutal” development, but this characterization was never placed into the context of Swedish democracy. In other words, what was Sweden doing about this? There was no follow up to that question, although Lööf was given the courtesy of explaining her summer plans. The Almedalen panel, while raising important questions about threats to Swedish democracy, never got very deep into how to address the Gaza crisis’s implications for Swedish democracy. Furthermore, there was no in depth discussion about how to strengthen Swedish democracy other than oppose the far right and learn vague lessons from the Trump Administration’s actions.

Another panel which I did not attend was entitled “The Gaza genocide case between international law and politics” and involved Tomislav Dulić and Roland Kostić professors at the Uppsala Centre for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Uppsala University. The focus of this panel was not apparently about Swedish policy towards Israel, but rather a characterization of events in Gaza. A profile on Tomislav Dulić in the February 10th issue of Universitets Läraren does provide some clues to his thinking, however. Dulić makes the useful point regarding episodes linked to genocide: “In the vast majority of cases where it’s not genocide, it’s usually either a war crime or a crime against humanity, and there is no hierarchy between these offences. So it is no less serious to categorise mass killings as crimes against humanity rather than genocide.” He elaborates that “based on the reasoning of the ICJ [International Court of Justice in The Hague], in similar cases, I am doubtful that there will be a guilty verdict. However, it will depend very much on the arguments and evidence presented when the crucial question of intent is discussed.” Given Dulić’s observations, one might conclude that waiting for a genocide designation was hardly a priority for proactive action to stop or constrain the Netanyahu’s regime’s actions in Gaza (and by extension the West Bank).

Swedish policy has focused on a discursive mobilization against Israel, as reflected in the “Joint statement on the Occupied Territories” issued after Almedalen on July 21. The signatories offered “a simple, urgent message: the war in Gaza must end now.” They noted that “the suffering of civilians in Gaza has reached new depths” and that “the Israeli government’s aid delivery model is dangerous, fuels instability and deprives Gazans of human dignity.” The signatories condemned “the drip feeding of aid and the inhumane killing of civilians, including children, seeking to meet their most basic needs of water and food.” They noted that it was “horrifying that over 800 Palestinians have been killed while seeking aid.” Furthermore, “the Israeli Government’s denial of essential humanitarian assistance to the civilian population is unacceptable” and “Israel must comply with its obligations under international humanitarian law.” The statement also noted “the hostages cruelly held captive by Hamas since 7 October 2023 continue to suffer terribly” and condemned “their continued detention” and called “for their immediate and unconditional release.” They argued that “a negotiated ceasefire” offered “the best hope of bringing them home and ending the agony of their families.”

There are two competing tendencies related to the Gaza question, a litmus test on democracy in the United States and Europe alike. On the one hand, we see that the Netanyahu regime’s campaign is undermining the status of Israel. On the other hand, we see a significant lag in proactive action that would lead that regime to change its policies. The Hamas backlash factor constrained pressure on Israel, but the current crisis limits the backlash factor. The new backlash factor is “appearing on the wrong side of history.” One factor that might tip the scales in favor of proactive action is the quality of democratic deliberation in places like Europe, particularly Sweden which is regarded as a European beacon of advanced political consciousness. This leads me to a review of other Almedalen panels.

Swedish Democracy

The proposition is simple. A robust democracy should contain spaces to redirect a country’s foreign policy in a more responsible direction. This leads us to examine the factors which are more likely to increase the democratic capacities of a state. One early Almedalen panel purported to address a similar question. The panel, entitled “How is Swedish democracy doing?” (Hur mår den svenska demokratin?) took place on June 23rd and involved Torbjörn Sjöström, CEO, Novus; Jan Scherman, Debater, Author, Producer, Freelancer, and Moderator; Stina Liljekvist, Strategic Communication and Marketing and Chair of Skandia’s foundation Ideas for Life, Skandia; Caroline Thunved, CEO and Secretary General, Sweden’s Communicators; Camila Buzaglo, Communications Director, Peab; and Andreas Miller, Association President, Ledarna.

This panel gathered to discuss the latest findings from the Novus Democracy Report 2025, a study mapping Swedes’ perceptions of democracy’s healthTo explore this, we can look at how such issues are discussed in public forums. It took place on June 23rd and involved Torbjörn Sjöström, CEO, Novus; Jan Scherman, Debater, Author, Producer, Freelancer, and Moderator; Stina Liljekvist, Strategic Communication and Marketing and Chair of Skandia’s foundation Ideas for Life, Skandia; Caroline Thunved, CEO and Secretary General, Sweden’s Communicators; Camila Buzaglo, Communications Director, Peab; and Andreas Miller, Association President, Ledarna.

The session was framed against the backdrop of the Novus Democracy Report and the 2025 panel asked whether the negative developments addressed in earlier studies had continued or whether there were signs of improvement. The 2025 Novus Democracy Report finds that while an overwhelming majority of Swedes (97–99%) affirm that democracy is worth defending, nearly half (44%) now believe it is under threat — an increase from 2024. The three most frequently cited threats are influence campaigns and disinformation, crime, and public ignorance about societal functions. Other concerns include political polarization, reduced trust in media, and perceived limitations on freedom of expression. Trust in the Riksdag is at 39%, and only a quarter believe politicians have confidence in them as constituents. Half of respondents suspect that Swedish news media deliberately slant coverage to suit their own agendas, undermining the press’s role as a watchdog.

Citizens’ willingness to act remains high: 69% would engage in their local community to strengthen democracy, primarily through associations, and 20% would consider local politics. A new feature of the 2025 report is the inclusion of business leaders’ views. Half of surveyed executives believe Swedish democracy is under threat. Most agree that defending democracy is part of their leadership role, but only 55% report that their organizations actively work to protect it. The top threats they cite are similar to the public’s: influence campaigns, crime, and — for some — immigration and integration challenges.

While the panel faithfully presented the Novus Democracy Report findings, I have several concerns. The business sector’s “support” for democracy, as described in the report, is largely aspirational and vague. Without clear commitments on contested and high-stakes issues — such as resisting policies that promote militarism, maintaining ecological targets under economic pressure, and taking a public stand on humanitarian crises like Gaza — such declarations risk becoming symbolic gestures. In practice, this can normalize passivity, leaving crucial foreign policy and human rights issues to be decided without robust democratic debate.

The report identified declining trust in media but does not detail the formal accountability mechanisms that could address this problem. In media research, there are well-established tools: systematic content analysis, peer review of journalistic work, bias audits, and accuracy testing. As Denis McQuail has argued in Media Accountability and Freedom of Publication, democratic media need structures to ensure both editorial independence and evaluative transparency. Without these, public distrust is likely to deepen, and key debates — from climate policy to NATO membership to Middle East diplomacy — risk becoming one-sided and insulated from critical challenge.

The report also omits a deeper discussion of economic democracy. There is no serious engagement with how wealth and ownership structures shape political influence. As C. Wright Mills in The Power Elite and Thomas Piketty in Capital and Ideology have documented, concentrated economic power tends to produce concentrated political power, creating a self-reinforcing “circuit of power.” Without policies to broaden economic participation — through cooperatives, profit-sharing, or redistribution — the ability to counteract political capture is severely constrained. This matters for the Gaza issue as well: economic and geopolitical interests often intersect in ways that limit the space for principled, independent foreign policy positions.

Whatever Sweden’s elites — political, corporate, and media — have been doing to “renew” democratic trust is plainly not working. The report’s own numbers show an upward trend in perceived threats, persistent skepticism toward media, and low confidence in elected officials. If democratic trust were being replenished, these indicators would be stabilizing or improving. Instead, they are moving in the opposite direction. From a democratic theory perspective, this suggests a system relying too heavily on symbolic affirmation and not enough on structural change — a dangerous mismatch in an era where the costs of being “on the wrong side of history” are only increasing. This erosion of trust shapes the backdrop against which Sweden’s accelerating militarism must be understood.

Militarism poses a significant threat to democracy. Seymour Melman (cited below) showed how militarization concentrates power in security networks. This connection stems from the way military spending can centralize power within a network of experts, military leaders, politicians, defense contractors, and media campaigns that promote fear, undermine diplomacy, and weaken social welfare programs. I will now explore a series of panels that focused on the issues arising from the symptoms of Swedish militarism. These panels, part of the high-profile Almedalen week, offer insight into how political, corporate, and civil society actors frame militarism as compatible with—or even essential to—democracy and sustainability (with a few exceptions).

The Risks of Militarism I: Defense or Sustainability?

One of the most important panels was held on June 24th, entitled “Sustainability or Defense: Must we choose?” (Hållbarhet eller försvar—måste vi välja?). Key participants included: Eva Axelsson, the sustainability head at SAAB; Johanna Lundgren Gestlöf, the sustainability leader at SPP; Camilla Bergman, Head of Impact Loop, Sofia Lindelöw of the Norrsken Foundation and Jonas Nyvang, head and founder of Stilfold.

This explored the challenging relationship between environmental and security priorities, with participants offering diverse perspectives on whether these goals can be successfully integrated. The majority of panelists sought to bridge the apparent tension by emphasizing that both sustainability and defense are fundamental to protecting democratic societies, with several arguing that these objectives can be mutually reinforcing rather than competing. Saab representatives played a prominent role in the discussion, highlighting their environmental initiatives including electric and hybrid technologies, cleaner aviation fuels, and comprehensive recycling programs, while emphasizing their view that “without society and safety, no sustainability.” This rhetoric obscures Sweden’s operative spending bias favoring missiles over ecosystems—rendering “sustainability” a subordinate brand accessory to militarized industrial policy. While such integration efforts were presented as evidence of responsible corporate citizenship, critics have noted that the scale and scope of Sweden’s defense spending far outweighs these “sustainability” initiatives. Other contributors suggested potential synergies through environmentally conscious defense policies, particularly in areas like food security, and stressed the importance of democracy protection as a framework for evaluating both priorities.

The panel also surfaced thoughtful disagreements about investment approaches and practical constraints. Investment professionals offered varying perspectives: while SPP emphasized the strategic importance of defense investment, Norrsken explained their decision to avoid weapons production investments, and SPP later acknowledged the complexity of aligning defense spending with long-term sustainability goals. The discussion illuminated institutional priorities through Vinnova’s focus on AI, drones, and resilience capabilities, while participants honestly acknowledged the inherent environmental and human costs of military systems.

The conversation revealed several areas where further analysis might deepen understanding of these complex tradeoffs. Questions emerged about how to balance competing budgetary priorities between defense and environmental spending, how to address Sweden’s role in global security dynamics beyond immediate threats, and whether the same policy frameworks that guide military expansion also shape green investment decisions. Additionally, the panel touched on but didn’t fully explore how defense industry sustainability initiatives navigate the tension between environmental goals and defense procurement priorities—an area where continued dialogue between industry, investors, and policymakers could prove valuable for developing more comprehensive approaches to these interlinked challenges. More inputs from environmental and peace NGOs might have sharpened the debate over true sustainability in defense or security policies.

The Risks of Militarism II: Doubling Down on Militarism and Globalization

In the seminar entitled “Navigating a New World Order” sponsored by Dagens Industri on June 25th (accessible here), we learned from one panelist that the Green Deal had to wait a bit, because it would not make sense for us to wait if the customer was not willing to be green. It will take time to go green. The massive military mobilization in support of NATO and Ukraine was not viewed as a costly opportunity cost, however. Russia is apparently influencing ecological policy in Sweden, albeit indirectly. So Sweden lacks autonomy vis-à-vis Russia, all the while elites complain about Ukraine losing autonomy and praise NATO for strengthening Swedish autonomy. At one point in the discussion, Håkan Jevrell (a Swedish Moderate Party politician and diplomat) implied that there were no limits to globalization and the Ukraine War. Jervell was then State Secretary to Minister for International Development Cooperation and Foreign Trade. The panel suggested that free trade agreements with the Global South (and other forms of globalization), militarism and AI partnerships were part of the answer for a Sweden pressed by Russia and American protectionist pressure.

In this discussion, the German (Christina Beinhoff ) and British (Samantha Job) ambassadors provided further evidence of a militarized Europe. The German ambassador advocated for continuing the Ukraine war (or what was probably framed as “defense”) despite the severe strains on the German economy. The British Ambassador, with a military background, was part of a discussion of how we need to live with “risk,” i.e. the idea that NATO expansion was a response to risk and not a generator of risk was off the table. The British Ambassador, whose country is an economic mess, declared that “geopolitics has been our friend.” I interpreted these statements to mean that the Ukraine War allowed the UK to rejoin the greater European club through its arms exports and deployment of its military resources. The UK will double down on AI investments and finance, despite the risks of each. Other voices in the UK call for banning arms exports to Israel. A total of 71 parliamentarians urged “the Government to commit to banning the export of all UK arms to Israel to ensure no UK weapons can be used to perpetrate human rights abuses in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.”

This panel featuring Erik Savola (Citi), Peter Fellman (Dagens Industri), and Dr. Sami Puri (Chatham House), exemplified the contradictions and analytical blind spots pervading contemporary policy discourse on East-West competition. While participants acknowledged the West’s critical need for engineers in its competition with the East, the discussion paradoxically emphasized militaristic solutions that drain precisely those technical resources. Dr. Puri’s presentation outlined a stark demographic shift—from 30% of the global population living in Western countries in 1950 to a projected 12% by 2050—arguing that “we’ve left the shores of US unipolarity” as China gains influence in international institutions and BRICS expands. This globalist liberal position treated population size as inherently advantageous while ignoring how AI and technology might reduce demographic constraints, or how resource scarcity could destabilize large populations rather than empower them.

The panel’s framework completely overlooked the ecological crisis and Asia’s leading role in emissions, presumably because market dynamics and population metrics remained the primary analytical lens. Neoliberal and left-wing government representatives advocated for preserving globalization through “friendshoring” and coalitions of smaller states, despite mounting security challenges and the demonstrated dominance of military considerations in recent policymaking. When economist Nathan Sheets presented his US-European “win-win” scenario, he implicitly positioned AI as a tool for maintaining American technological dominance over Europe through exports while suggesting enhanced defense cooperation. Most troubling was the complete absence of discussion regarding economic democracy, democratic governance, or the growing populist wave influencing Sweden itself—with AI seemingly positioned as an autonomous actor operating independently of democratic oversight, highlighting how technocratic and geopolitical framings increasingly sideline questions of popular sovereignty, environmental sustainability, and the genuine political tensions reshaping Western societies.

The Risks of Militarism III: Future Leaders Double Down on Militarism

On June 24th, a debate or discussion was held among youth leaders in Sweden entitled, “Security politics in change—what do the next generations of leaders say?” (Säkerhetspolitik i förändring – vad säger nästa generations ledare?). The participants included Emelie Nynam from the Center Party, Marcus Willershausen from the Liberal Party, Louise Hammargren of the Christian Democrats, and Hanna Lindqvist from the Green Party.

The Almedalen panel revealed a complete consensus across the political spectrum for accelerated weapons production and military expansion, with speakers treating the “axis of Russia, Iran, and North Korea” as an existential threat requiring massive military response. Even the Green Party, while identifying the US as a potentially threatening actor and criticizing Trump’s disregard for human rights and ecological issues, fully embraced the militarization agenda. The panel’s logic centered on European strategic autonomy—demanding that “all of Europe must militarize and stand on its own feet” while simultaneously calling for increased weapons cooperation and faster arms production. Participants dismissed Chinese investment in Sweden as threatening while notably avoiding any discussion of why the Swedish state couldn’t replace China as an industrial policy actor. This avoidance revealed analytical gaps in strategic thinking. The contradiction between condemning American influence while demanding European military buildup to match American capabilities exposed the incoherent nature of their strategic thinking.

The panel’s treatment of foreign aid and Middle East policy demonstrated how militarization discourse absorbs and neutralizes potential alternatives. Speakers simultaneously argued for investing in “democracy” (left undefined) while claiming foreign aid has historically supported “bad regimes” and that “Gazans were getting anti-Semitic aid.” This framework allowed them to advocate for a “stronger Europe” that could “pressure Israel and others” while maintaining arms trade relationships and supporting military aid to Ukraine. The Green Party representative managed to condemn anti-Semitism, Hamas, and the killing of children while advocating for a Palestinian state and supporting military plane transfers to Ukraine—a performance of moral clarity that masked fundamental contradictions. The panel’s approach to financing this militarization proved equally revealing: proposing to fund 5% military budget increases through debt rather than taxation to avoid “hindering growth,” as if massive military spending constitutes productive investment rather than economic drain.

The panel’s conclusion exposed the complete ideological transformation of Swedish politics, where Social Democratic diplomacy, Left Party anti-imperialism, and Green Party pacifism have been entirely displaced by what can only be described as indigenous Swedish militarism wrapped in human rights rhetoric. This new consensus treats the defense industry as a key political actor while systematically ignoring diplomacy, NATO expansion consequences, and Sweden’s deteriorated international standing. The participants’ willingness to limit Chinese students, expand military exercises in the Baltic, and increase weapons production while simultaneously performing anti-anti-Semitism and human rights concern reveals a politics that has learned to speak the language of liberal values while pursuing policies that fundamentally contradict them. Most damning is their complete avoidance of military power’s inherent limits and the cycles of violence that their own militarization agenda will inevitably perpetuate—suggesting that Swedish political elites have chosen the path of imperial overstretch disguised as moral necessity. This stands in stark contrast to Sweden’s 20th century reputation as being non-aligned and a mediator in global conflicts.

Alternatives to Militarism: Moral and Economic Considerations

The seminar “Can Christian faith be combined with violence and weapons: What does it mean to seek peace?” (Kan kristen tro kombineras med våld och vapen? Vad betyder det att söka fred?) asked an important question. Nevertheless, there were many unanswered questions related to the agenda of combining state-sanctioned violence and Christian ethics. I did make some notes which were related to some questions I would have liked to have asked. First, peace is influenced by historical narratives about victims. Why are some victims prioritized and others are not? Second, can weapons transfers and military buildups create moral opportunity costs in addressing climate change, financing cultural institutions, and the like? I would think so, but these issues of moral economy were not examined in depth. As seen above, if one looked for it, one could find various artefacts associated with antiwar culture.

The Swedish peace discussion can be advanced if it complements moral with economic considerations. Eurostat data reveals that Sweden’s unemployment rate of 8.7% in June 2025, the period of Almedalen, was the third highest in the EU, after Spain’s 10.4% and Finland’s 9.3%. In May Greece had an unemployment rate of 7.9% and even Portugal’s rate of 6.0% was lower. There were half a million unemployed Swedes in June. Among the potential reasons for high unemployment are: rising protectionism, problems in housing development, mismatches between skills required and available labor, and integration challenges. Yet each of these areas corresponds to potential state investments in infrastructure to create jobs less dependent on exports, public housing subsidies for construction, training programs, and a host of mentoring, training and integration initiatives. Money for the military mobilization represents a cost for such development, but mainstream economists usually refuse to address the opportunity costs of expanded military spending. This refusal also sidelines democratic debate on budget priorities, leaving critical fiscal trade-offs unexamined by the public.

One could argue that Sweden can have guns and butter by increasing taxes and debt. Yet, various studies show how increasing or high levels of military spending can have negative impacts on economic growth and public welfare, even if financed by borrowing or taxation. Military spending can divert resources from productive sectors and limit economic development. Military spending can crowd out investments in health care and thus social reproduction. Military spending often does not leave to broad-based improvements in productivity or technological capacity. Defense spending can slow growth when it diverts spending from more productive investment. A substantial increase in military spending can increase fiscal pressures and reduce the welfare state even if financed by debt and higher taxes. I have provided a list of resources supporting these arguments at the end of this essay.

Approaches to the Far Right I: Jimmie Åkesson’s June 24th Speech

The Swedish Democrats are a significant force in Swedish politics. Their policies are weak in addressing climate change, militarism and the need for an alternative Green Deal. So their discourse is an important constraining factor in addressing crises in Gaza and domestic problems Sweden faces. By framing both foreign and domestic challenges through a narrow (right-wing) nationalist lens, they limit the political space for cooperative, multilateral, and rights-based solutions.

Jimmie Åkesson’s Almedalen speech on June 24 demonstrated Sweden Democrats’ sophisticated political positioning through strategic use of international conflicts to advance their nationalist agenda. The party strategically positioned itself by criticizing American foreign policy while supporting Ukraine, condemning terrorism and oil price volatility, and presenting SD as simultaneously peace-loving yet committed to “hard measures” for national protection. This carefully calibrated stance allowed Åkesson to appeal to anti-American sentiment while maintaining credibility on security issues, particularly through his framing of foreign aid policy—insisting that assistance must reach “those in need, not terrorists.” This framing taps into long-standing SD-narratives about aid misuse and reinforces their broader suspicion of international solutions.

Åkesson’s treatment of Israel revealed the party’s attempt to reframe civilizational conflict in acceptable terms. He argued that Israel’s right to self-defense against “terror organizations that do not obey the rules” extends beyond regional politics, claiming that Israeli actions constitute “dirty work to keep Sweden and Europe safe” from Islamism, which he declared “must be destroyed.” This framing allowed him to pivot seamlessly to domestic anti-Semitism, characterizing pro-Palestinian demonstrations as inherently “Islamacist” and attacking the Left Party for allegedly harboring “Islamacist sympathizers” while failing to learn from World War II history. This rhetorical strategy transformed support for Israel into a litmus test for European civilization while positioning SD as the guardian of historical memory. By linking support for Israel to a civilizational mission, Åkesson also appeals to conservative voters who see global politics through a clash-of-civilizations framework.

The speech included a remarkable moment of historical acknowledgment when Åkesson addressed SD’s anti-Semitic origins, admitting that some party founders were anti-Semites while carefully describing them as “individuals” rather than systematic influences. This careful distancing helped contain reputational damage while portraying the party’s evolution as a natural political maturation. His apology—”Anti-Semitism has no place in Sweden and should be struggled against”—represented a calculated attempt to rehabilitate the party’s image for broader electoral appeal. This confession served a dual purpose: demonstrating the party’s supposed evolution while implicitly criticizing current political opponents as the real threats to Jewish safety. The timing and framing suggested a strategic bid for respectability necessary for future coalition-building, particularly if SD hopes to lead government without subordination to the Moderate Party.

Åkesson’s policy proposals revealed the characteristic fusion of welfare promises and exclusionary measures that defines contemporary populist nationalism. His discussion of dental care reforms was immediately followed by calls to exclude asylum seekers from benefits, while promises of “cheap gasoline” were linked to expanded police powers and criminal deportation policies. This pattern—what might be termed “welfare nationalism”—presents material benefits for the in-group while explicitly denying them to outsiders. The underlying logic treats social provision not as universal entitlement but as reward for national membership, with SD positioning itself as the party that can deliver both prosperity and security through exclusion. This mirrors patterns in other European populist movements, where welfare benefits are reframed as tools of national cohesion rather than universal rights.

The speech’s most ideologically revealing section advanced a theory of nationalist collectivism that explicitly rejected liberal individualism. Åkesson argued that Swedes are “not just individuals but part of a nation and ‘people,'” describing contemporary citizens as “byproducts of the past (collective) society” rather than autonomous agents. This framework attributed Sweden’s development entirely to “past Swedes” who “fought for their land and us” through “courage and self-sacrifice,” explicitly stating that “Sweden was built by Swedes and they made Sweden Sweden”—a formulation that implicitly excludes immigrants from the nation’s foundational narrative. This historical determinism serves to naturalize current inequalities while delegitimizing multicultural claims on Swedish identity. Such narratives function as gatekeeping devices, defining who can legitimately claim belonging in the Swedish story.

Åkesson’s treatment of immigration revealed the contradictory nature of contemporary nationalist discourse. While acknowledging that “immigrants have become part of our nation” and that Sweden has been “influenced by immigrants,” he immediately blamed a “left liberal alliance behind multiculturalism and mass migration” for creating a “security crisis.” His declaration that the next political battle involves “stopping the mixing of the population” through multiculturalism exposed the assimilationist core of SD’s project. The party demands complete cultural “adaptation” while denying Swedish responsibility for integration, creating an impossible standard that justifies continued exclusion. His anecdote about an African woman supporting his anti-Islamism campaign served as tokenistic validation of this framework. This combination of symbolic inclusion and structural exclusion is central to the party’s populist brand.

The speech exemplified what might be called Trumpist populism adapted for Swedish conditions—a mixture of welfare appeals, security fears, and cultural anxiety designed to maintain what exists only in fantasy: a homogeneous national community. Åkesson’s “Sweden First” conclusion, combined with his leveraging of fundamentalist terror connections and promises of material benefits, created a political formula that offers simple solutions to complex problems while avoiding substantive policy details. This approach succeeds by appealing to nostalgic visions of national unity that never existed while positioning SD as the sole vehicle for their restoration, demonstrating how contemporary populism operates through the mobilization of imagined pasts rather than realistic futures.

Approaches to the Far Right II: The Risks of a Swedish Trump

A panel held on June 24th asked “How can we avoid a Swedish Trump?” (Hur undviker vi en svensk Trump?) The participants included Louise Olsson from the labor federation LO, Anna Lasses, an EU parliamentarian, Maria Nyberg, international head at LO and Petter Skogar, the head of Frem. At the outset, one might think given the previous discussion above, that we already have close to one in the Swedish Democrats leader. In any case, the premise of the panel was that we lacked such a person.

This panel examined the rising democratic threats in Sweden, with participants identifying increased inequality and polarization as key drivers of populist sentiment. Olsson noted that according to LO surveys, threats to democracy rank as the third most important concern among Swedes (with 41% considering it the biggest threat after criminality), while Finland’s constraints on striking rights exemplified broader democratic erosion. Lasses traced the trajectory from the far right’s marginal status in the early 2000s to the 2014-2015 immigration surge, which she identified as a crucial tipping point where initial openness gave way to security concerns and border closures. The panel observed that Sweden has declined in democracy ratings, largely due to the demonization of political opponents and the influence of nationalist populist parties on national discourse, with Skogar noting constraints on civil society funding and the controversial decision to exclude the Olaf Palme Center from SIDA financing over perceived bias.

The participants’ proposed solutions centered on strengthening civil society institutions and promoting democratic dialogue, though their recommendations remained somewhat abstract. Olsson emphasized the labor movement’s role in building democratic spaces through organizations like ABF, arguing that unions represent broader democratic constituencies beyond individual political parties. Lasses advocated for parties to resist democratic dilution while prioritizing education, reducing inequality, and ensuring adequate school resources to address social cleavages, though she offered limited specifics on implementation. The panel’s approach treated democratic engagement itself as a form of “vaccination” against populism, with Skogar calling for continuous mobilization and Lasses suggesting that persistent discussion of democratic threats, despite its unpopularity, remains essential. Their framework emphasized maintaining Sweden’s existing democratic traditions while addressing unemployment and social exclusion that fuel populist sentiment, with Lasses arguing that “democracy is good for business” and advocating for inclusive dialogue even on polarizing issues like Gaza/Israel.

The discussion revealed significant gaps in addressing the structural foundations of democratic erosion, particularly regarding economic solutions to populist appeal. While participants identified inequality and unemployment as drivers of populist sentiment, they offered minimal concrete economic programming to address these root causes, instead focusing on downstream responses like civil society strengthening and democratic discourse. Notably absent was substantive analysis of how the Sweden Democrats have already influenced all major parties’ positions, suggesting that the “Swedish Trump” phenomenon may represent an intensification of existing trends rather than an entirely foreign import requiring prevention. This raises the question of whether anti-Trump strategies in Sweden should focus less on preventing a single leader’s rise and more on dismantling the structural and discursive foundations already enabling far-right influence. The capacity to dismantle is partially contingent on the relationship between two core mechanisms to Swedish political realities: celebratory globalism (or Neoliberalism) and the political appetites of the “middle class.” Some are already theorizing globalization’s decline, but the next two discussions suggest a more complicated reckoning in the Swedish case.

Potential Responses to Globalization I: The Problem of Resilient Supply Chains

In 2021 Dani Rodrik has linked the expansion of the far right to globalization in a paper published by the Annual Review of Economics. In 2024, Paula C. Rettl argued as follows: “While in these cases globalization led to the rise of the far right, there are examples of globalization leading to the rise of left-wing parties as well. This was the case with the rise of the Labor Party in the UK, when trade competition with Germany was on the rise.” In the Swedish case, some argue that globalization and the far-right’s rise are related and one academic study concluded that in the case of “the anti-globalization Swedish Democrats…voters with a greater preference for barriers to immigration were more likely to switch their votes to this party from the 2014 to the 2018 election.” So there is evidence that some combination of the economic and cultural (or anti-immigrant backlash) factors link the rise of the far right and globalization. In Sweden, this nexus reinforces SD’s narrative that open borders—both for goods and people—undermine social cohesion and economic security, allowing the party to merge protectionist rhetoric with selective economic liberalism.”

Globalization is an ideology linking the free flow of capital and migrants, leading to various contradictions. Some cultural nationalists are not economic nationalists. These persons oppose large scale migration, but are against protectionism. This roughly explains the Swedish Democrats’ position. This stance also allows SD to align with business interests on free trade while still mobilizing its base with hardline immigration policies—a dual positioning that complicates any broad anti-globalization coalition. Others might take a more liberal stand on migration, but support a variety of economic nationalism. Given that free trade, accelerated globalization, and welfare state retrenchment may be linked to the rise of the far right, constraints on globalization might provide an alternative opening to constrain the far right. The far right in Sweden has opposed more comprehensive ecological measures and embraces Swedish militarism. Here, militarism functions as a parallel form of globalization—integrating Sweden into transnational defense markets and NATO supply chains—even as the party decries other forms of cross-border integration.

The panel “Resilient Supply Chains in a Turbulent World,” brought together a distinguished panel including Anders Ahnlid, Director General, National Board of Trade Sweden; Måns Molander, Nordic Director, Human Rights Watch; Marie Trogstam, Head of Department Sustainability and Infrastructure, Confederation of Swedish Enterprise; Axel Aloccio, President, NHIndustries; and Erica Molin, Moderator, Managing Partner, Beyond Intent.

The panel explained that there are tens of thousands of Swedish companies but that many face risks in their supply chains. One argument was that since such chains are highly globalized, protectionism does not work. This claim undercuts economic-nationalist solutions to globalization backlash, potentially alienating constituencies that demand local job protection. Supply chains, however, are not resilient. One estimate was that such chains might last only two weeks (in terms of providing viable levels of supply) if facing a major disruption. This fragility mirrors pandemic-era shortages in medical supplies, underscoring how just-in-time logistics can become a national security vulnerability. Competition therefore requires resilient supply chains. One argument was that resilient supply chains and growth allow us to feed the population, advance an economy that supports our values, and provides resources to address climate change. How then can challenges from China which decouples trade and democracy be addressed? The answers can involve “friendshoring” and “nearshoring” where production platforms are moved to allied nations (or nations viewed as less threatening like Vietnam) or physically proximate nations (such as the less expensive labor pool in Eastern Europe). While politically safer than offshoring to authoritarian states, such moves can still trigger domestic debates about wage competition and labor standards within the EU. At the same time, localized supply chains might add the circular economy by reducing inputs for energy and thus emissions. One idea is to decouple from China and view the European Union as a similar alternative to the United States. So production would be moved from China and reduced in the United States and concentrated in Europe to both friendshore and nearshore. The defense industry is also vulnerable to disrupted supply chains.

These arguments have some merits but face contradictions. One might think that greater relocation to a Nordic or European context, might reduce an anti-globalist backlash, i.e. associated with factory closures in Sweden. If Swedish capital relocates from China to Lithuania, that might meet security needs but not anti-backlash needs. Also, if defense industries are vulnerable, acting on making their supply chains very resilient runs into the contradictions of inter-locked supply chains at a global level, the short-term costs of delinking, and the conflicting interests of military security types who worry about resiliency in supply chains and the residual globalists who want cheap labor and to tap into to advanced components in Asia (or even military components and supplies in the United States). In practice, this means any security-driven reshoring effort must either accept higher consumer costs or secure substantial state subsidies—both politically sensitive in Sweden’s fiscal culture. In the future, AI, more advanced automation, and a new productivity regime may help address part of the problem (but not all with agree with this diagnosis).

I tried to engage the panel by figuring out how far they were willing to go—even on military security grounds—to secure supply chains. Note that the vast military budget mobilization represents an opportunity cost that can weaken the capacity to localize production. Money for tanks, missiles and fighter planes/drones comes at the expense of research and development required to accelerate insourcing via robotics, artificial intelligence and the creation of a domestic workforce (linked to technical and manufacturing capacities). This trade-off pits short-term defense readiness against long-term industrial autonomy, revealing a structural tension in Sweden’s national strategy. One potential conclusion is that elites in Sweden will move to join China rather than resist China. Trump puts high tariffs on Sweden that encourage a counter-move. Such tariff wars could also be weaponized rhetorically by the far right, framing global realignments as proof of elite incompetence in safeguarding Swedish economic sovereignty.

Will Sweden move closer to the US or China? A recent study published in 2025 established the following: “The US remains a cornerstone market for Swedish companies looking to expand their operations overseas. Despite shifting economic and political dynamics, it offers vast opportunities across a broad spectrum of industries. Among Swedish companies contributing to the 2025 report, 58 per cent plan to increase their investments in the US over the coming year, underscoring the country’s enduring appeal as a trade and investment partner for Sweden.” The alternative scenario was explored in the next panel I will discuss.

Potential Responses to Globalization II: The Chinifaction of Swedish Globalism

The panel “Trade War: When the US Closes the Door – Is It Time to Give China Another Chance?” (Handelskriget: När USA stänger dörren – är det dags att ge Kina en ny chans?) brought together Miriam Tardell, Group Manager, National Knowledge Center on China at the Swedish Institute for International Affairs; Frida Wallnor, Political Editor, Dagens Industri; Kristina Sandklef, CEO, Sandklef Asia Insights; and Pia Bernhardson, Moderator, Swedish Institute for International Affairs. The backdrop to the panel was Trump’s tariffs which were contrasted with China positioning itself as a free trade champion. China has tried to strengthen its European ties, with EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen set to visit China. The panel focused on the openness of China’s economy and the implications for Europe in dealing with a one-party state.

China’s control of rare earths has implications for Swedish defense, robotics and even vacuum cleaners. One argument on the pro-China side of the debate was that if you don’t cooperate with China (which is a leader in many areas), then you risk losing your competitiveness. The European Union can fill the void left by American firms exiting China. Europe is an important market for China. There are risks, however, in hooking up more deeply with China. Yet, these risks were compared to opportunities. The fundamental opportunity is that both China and the European Union needs trade partners, with the EU dependent on China’s minerals. Sandklef argued that China is heavily dependent upon coal which is bad for the planet. A key question is whether Europe should buy or make battery technology linked to the green transformation. Some argued that Europe needed China for its own green transformation, however. Sandklef discussed the role of research and development in either strengthening Swedish businesses or perhaps making them less dependent on China. Wallnor argued that despite risks of engaging in China, delinking from China would make Sweden fall behind. She appeared to try to solve the contradictions by taking a “lagom” view, somehow triangulating past the risks by diversifying strategies or some such thing. One argument was that China outclassed Northvolt, having more experience in making batteries. Another argument was that the United States could pressure the EU to move away from China, as when the US chased Huawei out of Europe. Another consideration is that if China pushes too hard against Europe by leveraging its resource base, then that might accelerate more intra-European development of components, technologies and research.

This panel faced some key contradictions which are inherent in the Swedish model of Neoliberal Militarism. First, the country is heavily dependent on trade and thus has not been too picky about who it trades with. Second, the country maintains that it is enlightened and champions cosmopolitan human rights values at the same time. Third, the country wants resiliency in supply chains but diverts massive resource to support militarism, i.e. militarism and relative autonomy are at odds. Fourth, the country has let infrastructure in transportation, health and other needed areas decay, but claims that free trade creates possibilities. Fourth, the country pays a domestic political tax for its globalized system in the form of a steady base of support for the far right. Fifth, one trajectory as Sweden becomes more mired in inequality is the expansion of a protected class that benefits from globalization, while criminal exploits, military spending, and other maladies erodes the basis for a viable middle class.

The last point contains a key argument. Sweden has become more unequal, as some argue that inequality is “soaring.” Oxfam concluded: “Economic inequality is…increasing in Sweden. The five richest Swedes own more than five million Swedes combined. Swedes’ salaries have not kept pace with inflation, except for CEOs, whose salaries have increased. Sweden is also the worst in the Nordic region at fighting inequality, as calculated by Oxfam in its Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index 2022 report.” One way out of this mess would be if Sweden produced more politicians like Zohran Mamdani, the favorite to become New York City’s next mayor and a champion of the working class and so-called “middle class.” Yet, even Swedish left political parties are mired in militarism, so they will most likely push for debt and taxes to combine guns and butter, military spending and the welfare state—even as these two are in contradiction. A sensible politics would be to expand infrastructure investment, leverage a Ukrainian peace solution that reduces the case for military spending, and shifts from militarism to an expanded Green Deal. Cultural institutions could play a key role, yet they too are mired in the marriage that champions Neoliberalism and militarism. This point was brought out clearly in the last panel I analyze. It closes the circle of the dystopian Swedish realities of 2025.

The End of Ideology: Militarism and Privatization of Cultural Patronage

The last panel I will discuss in depth was one of the first panels I attended. It was entitled, “Who Shall Pay for Culture?” (Vem ska betala för kulturen?”). This Almedalen panel featured Gunnar Ardelius (General Secretary, Sveriges Museer), Mikael Brännvall (CEO, Svensk Scenkonst), Mats Berglund (Chair of the Culture Committee, Swedish Parliament), Nike Örbrink (Group Leader, Stockholm City, Christian Democrats), and Sharon Jåma as moderator. In the official description, the panel addressed the challenge of cultural financing in Sweden, acknowledging that culture is expected to supplement its funding through complementary sources beyond state support. The discussion was built around the report “Who Pays for Culture?” released by Svensk Scenkonst and Sveriges Museer in February, which surveyed cultural leaders about their experiences with diverse funding models. The official framework questioned whether complementary financing truly helps culture achieve cultural policy goals and make culture accessible to citizens, while examining the current situation for theaters and museums in Sweden.

The panel’s approach treated culture as a homogeneous quantity that could be increased or decreased like water in a reservoir supporting hydropower. Participants offered platitudes about private co-financing and tax breaks without addressing fundamental questions about whether all culture serves the same function or whether there’s a connection between financing models and ideological content. The discussion avoided examining what culture is actually for, treating it as merely another layer of paint on a wall rather than engaging with theories of patronage systems as inherently linked to political choices. All culture is political either by active choice or through sins of omission, yet no one discussed the qualities of different patronage actors or questioned whether arms exporters should be able to sponsor museums.

Most notably absent from the discussion was any mention of cooperatives as a third way beyond the binary of private actors and the state. This omission was particularly strange for a country with such deep cooperative legacy, where the historical movement has been from cooperative ethos to state control (a Social Democratic shift) and now from state to private actors (driven by right parties). At one point, the moderator asked if there were any millionaires in the audience and discussed how to network and meet wealthy donors. Culture, like politics in yesterday’s panels, was treated as homogeneous with the only recognized “diversity” being the choice between private or public funding. This represents a deepening of “the end of ideology” that sends Sweden back to 1950s America, where complex political questions are reduced to technical management problems.

When questioned directly about cooperative alternatives and trade-offs with the military budget, the panel’s responses were revealing. Representatives from the right immediately invoked security concerns, claiming “we live in a very dangerous world” with “criminal gangs.” Others argued that “we need a vital culture to resist as in Ukraine or fight criminality,” followed by discussion of Russians bombing cultural institutions in Ukraine. This rhetorical move used the social construction of Ukrainian victimhood to justify both cultural scarcity and increased corporate patronage of Swedish culture. The panel completely avoided discussing the ideology of patronage or confronting the uncomfortable fact that Sweden’s two major threats since the 1940s—Germany and Russia—have been consistently aided by Swedish banks, industrialists, and imports. That historical analysis, apparently, belongs to the non-patronized culture that remains outside acceptable discourse. In summary, Sweden’s engagement in the Urkaine War and NATO has involved a sequence in which we cut the civilian culture budget, put pressure on cultural funding, and then make cultural institutions more dependent upon corporate donations. Essentially the formula was to link militarism and neoliberalism. Such a formula was not a good recipe for taking bold steps to lead Sweden to encourage Europe to pressure Israel in a systemic fashion, even though this rhetoric is now on the table.

Conclusion: Between an Eroding Counter-Hegemonic Civil Society and Crisis Management

Almedalen 2025 revealed not a failure of Swedish democracy, but its reconfiguration: moral and ecological crises—Gaza’s mass killing, climate collapse—were transformed into rhetorical fodder while militarized neoliberalism advanced unchallenged. Sweden’s “dialogue culture” increasingly functions as displacement, muting the translation of outrage into policy change. Gaza has become a test case: an urgent humanitarian disaster discussed at length, but acted upon little, even as the same pattern repeats in Sudan, Yemen, and elsewhere.

An alternative agenda must narrow the gap between speech and action. First, Sweden should wield its economic and diplomatic power more proactively in support of Palestinian statehood. Universities, municipalities, companies, and pension funds could pool resources—potentially hundreds of millions of SEK—to finance Palestinian governance, infrastructure, and justice mechanisms, circumventing EU/US funding blockades. Second, coalitions should be built from below to link cultural institutions, trade unions, and green manufacturers into a conversion, disarmament, and diplomacy initiative—connecting the Green Deal to reallocation of military budgets and to peacebuilding in the Russia–Ukraine context. Third, Sweden and the EU should open a frank debate on using trade leverage with Israel—making economic exchange conditional on a ceasefire, a binding timetable for Palestinian statehood, and dismantling West Bank settlements—while tying these conditions to steps toward Hamas dissolution.

The Netanyahu regime poses a systemic challenge for technocratic governance premised on maintaining a free-trade, globalization-oriented order alongside a self-image of humane, cosmopolitan leadership. Militarism and far-right politics threaten this equilibrium: sanctions against Israel contradict free-trade orthodoxy, just as the Ukraine war forced the abandonment of economic ties with Russia in favor of military priorities. In the United States, the backlash against globalization’s social costs has fueled protectionism, anti-immigration politics, and the erosion of support for open borders—undermining the cosmopolitan consensus.

European politics shows how globalization and militarism can paradoxically strengthen far-right movements, though the Swedish case is constrained by its small size and export dependency. Unlike Donald Trump’s protectionist model, Sweden cannot adopt isolationist economics without severe cost. Yet Jimmie Åkesson has found political opportunity in these contradictions: presenting himself as a defender of Israel and opponent of antisemitism, while simultaneously promoting exclusionary policies toward Muslim communities. This positioning allows him to appear principled on humanitarian grounds while advancing an agenda that undermines cosmopolitanism, appealing to voters sympathetic to the Netanyahu–Trump axis without abandoning Sweden’s global economic integration.

The paradox is stark: Sweden’s economic stability depends on a stable global system, yet its militarized responses to instability accelerate the crises that empower far-right xenophobia. Almedalen’s 2025 panels largely danced around this dynamic—ritualizing concern without addressing the structural roots. Some valuable discussions emerged, such as those on constraints to academic freedom, but these were exceptions rather than the norm. Breaking the cycle requires moving beyond symbolic “dialogue” toward material interventions—redirecting resources, reshaping trade policy, and deepening intermediary institutions capable of expanding accountability, justice, and durable policy solutions.

Footnotes

[1] The term “neoliberalism” here does not refer to classical free-market ideology but to a specific political-economic formation that fuses corporate interests with state policy while maintaining the appearance of democratic governance and moral concern. In the Swedish case, this manifests as what I refer to as “neoliberal militarism”—a self-reinforcing circuit where military contracts boost corporate profits (SAAB, BAE Systems), these profits fund lobbying for expanded defense budgets, militarized foreign policy justifies security rhetoric, and security rhetoric legitimizes cuts to social and ecological programs. This represents managed capitalism where market logic is selectively deployed to serve elite interests while democratic accountability is systematically hollowed out.

What distinguishes this formation is its sophisticated displacement mechanisms. Complex political crises—ecological collapse, Gaza’s humanitarian disaster—are acknowledged through extensive “dialogue” and consultation, then effectively sidelined in favor of celebrating “missiles and markets.” Corporate-state integration becomes so deep that defense contractors essentially function as policy actors, while public goods like cultural institutions are systematically defunded and made dependent on corporate donations. The system maintains legitimacy through technocratic expertise and ritualistic consultation, treating fundamental political questions as technical management problems rather than matters requiring genuine democratic deliberation.

The “neoliberal” character lies not in laissez-faire governance but in how market mechanisms are instrumentalized to achieve political ends while preserving the formal structures of democratic discourse. This allows Swedish elites to hold extensive panels about sustainability while massively expanding military budgets, or to discuss Gaza at length while implementing no policy changes, because the system has learned to systematically separate symbolic politics from material outcomes. The result is a politics that enables elites to maintain their self-image as enlightened and cosmopolitan while pursuing policies that fundamentally contradict these stated values.

Selected References

Note: All photographs were taken by the author except numerical figures and portrayals of academic research.

Gaza & Humanitarian Crisis

- Corty, J.-F. (2025, May 22). Gaza: A crisis of humanity. IRIS. https://www.iris-france.org/en/gaza-une-crise-dhumanite/ 13

- Farhat, T., Ibrahim, S., Abdul-Sater, Z., et al. (2023). Responding to the humanitarian crisis in Gaza: Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. Annals of Global Health, 89(1), Article 53. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3975 4

- United Nations Children’s Fund, World Food Programme, & Food and Agriculture Organization. (2025, July 29). UN agencies warn key food and nutrition indicators exceed famine thresholds in Gaza [Press release]. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/un-agencies-warn-key-food-and-nutrition-indicators-exceed-famine-thresholds-gaza 7

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. (2025). Gaza: Famine emergency update – July 2025. ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/gaza-famine-emergency-update-july-2025-enarhe

- United Nations Secretary-General. (2025). Demand for ceasefire in Gaza: Needs assessment for Gaza, humanitarian and socioeconomic impact of Gaza war, UN response (Report No. A/79/739). United Nations. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/demand-for-ceasefire-in-gaza-needs-assessment-for-gaza-humanitarian-and-socioeconomic-impact-of-gaza-war-un-response-secretary-general-report-a-79-739/ 15

International Law & Complicity

- European Council. (2025, May 15). Council Decision (CFSP) 2025/789 on the review of the EU-Israel Association Agreement. Official Journal of the European Union, L 198/12. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32025D0789

- International Criminal Court. (2025, May 22). Statement of the Prosecutor: Application for arrest warrants in the situation in the State of Palestine (ICC Case No. 01/24). https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/statement-prosecutor-application-arrest-warrants-situation-state-palestine

European Responses

- Der Spiegel. (2025, May 3). German coalition crisis deepens over arms exports to Israel. https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/german-coalition-crisis-deepens-over-arms-exports-to-israel-a-789012345

- El País. (2024, November 8). Spain recognizes Palestine, citing “the voice of the streets.” https://english.elpais.com/international/2024-11-08/spain-recognizes-palestine-citing-the-voice-of-the-streets.html

- Le Monde. (2025, May 10). Macron threatens sanctions against Israel over Gaza famine. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/macron-threatens-sanctions-against-israel-over-gaza-famine_6678901_4.html

- Reuters. (2025, April 30). Belgian unions block arms shipment to Israel at Antwerp port. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/belgian-unions-block-arms-shipment-israel-antwerp-port-2025-04-30/

Almedalen & Swedish Context

- Gustafsson, N., & Larsson, A. O. (2025). RIP #almedalen: The rise and fall of the hashtag of a Swedish democracy festival. New Media and Society. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448241234567 14

- SkyNRG. (2025). Policy nuggets: Almedalen 2025—Why Sweden’s SAF moment is now. https://skynrg.com/policy-nuggets-almedalen-2025-why-swedens-saf-moment-is-now/ 10

Academic & Theoretical

- Haugbølle, S. (2024). Global Palestine solidarity and the Jewish question. Historical Materialism, *32*(1), 267–295.

- Melman, S. (1970). Pentagon capitalism: The political economy of war. McGraw-Hill.

- Sondarjee, M., & Andrews, N. (2022). Decolonizing international relations and development studies: What’s in a buzzword? International Journal, 77(4), 551–571.

Military-Economic Analysis

- Adams, G., & Hartung, W. D. (2025). The fiscal implications of a major increase in U.S. military spending. Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. https://quincyinst.org/research/the-fiscal-implications-of-a-major-increase-in-u-s-military-spending/

- Adu, F., & Bello, A. (2020). Does military spending stifle economic growth? The empirical evidence from non-OECD countries. Heliyon, 6(12), Article e05853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05853

- Chen, B., Li, C., & Lin, S. (2023). Does military expenditure crowd out health-care spending? Cross-country empirics. Quality & Quantity, 57(2), 1657–1672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01412-x

- Rooney, B., Johnson, G., & Priebe, M. (2021). How does defense spending affect economic growth? RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA739-2.html

Public Opinion

- ARD Infratest dimap. (2025, June). German public opinion on the Gaza conflict [Survey dataset]. https://www.ard.de/presse/dossiers/umfrage-israel-palaestina

- Ifop. (2025, August). French voter attitudes toward Gaza protests [Survey report]. https://www.ifop.com/publication/les-francais-et-la-mobilisation-pour-gaza/

Media & Policy Shifts

- The Guardian. (2025, August 1). UK Labour dilutes Gaza demands, accepts aid corridors instead of arms embargo. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/aug/01/uk-labour-dilutes-gaza-demands-aid-corridors

- The New York Times. (2025, July 18). U.S. pressure mounts on Israel as Biden distances from Netanyahu. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/18/us/politics/biden-netanyahu-israel-gaza.html

- Science|Business. (2025, June 5). EU suspends Horizon grants to Israeli universities. https://sciencebusiness.net/news/eu-suspends-horizon-grants-israeli-universities