By Jonathan Michael Feldman, September 3, 2023

The Culture of Bear Hunting

A prevailing stupidity and psychological indifference that prevails in foreign policy (such as arms exports that rob public welfare and support thugs), can also be seen in domestic policy, here the policy of hunting. The Swedish bear hunt helps us understand this dynamic very well. The two concerns are clearly linked. In both cases (hunting and arms exports), violence is being propelled at the expense of some other entity (bears or the civil society in the arms recipient nation). In both cases, the entity promoting the violence (human being or Swedish arms exporter) is the far greater threat. Finally, in both cases a lot of technocratic nonsense and humanistic discourse about preserving something (be that “human rights,” “security” or sheep) is used to justify what is an outrageous sadism.

We need to draw a distinction between hunting for survival, as part of sustainable ecosystems, and hunting as part of communities’ surplus growth and self-indulgence that is out of control. We have had certain communities which hunted bear to reproduce the human species. The problem is now we have bear hunting which is part of a larger ecocidal development to undermine all species.

In Native American tradition: “Bears are symbols of wisdom: often featured as guardians, teachers, leaders, and healers in Native origin stories, myths, and legends.” Some reports on Sami culture explain how bear hunting is legitimate, just like in Native American culture, which includes references to the Sami bear feast. In North America, the “Inuit continue to hunt seals, whales, walruses, and polar bears for subsistence.” Some draw a distinction between “traditional” and “recreational bear hunting,” the former involving indigenous communities and “deeply ingrained in cultural and spiritual practices and…often conducted with a deep reverence for the animal.” The latter “is often viewed as a leisure activity and may not have the same cultural and spiritual significance.”

There are tendencies within the Native American community to oppose the bear hunt or at least support bear preservation. For example, in 2013 Don Shoulderblade, Northern Cheyenne Sun Dance Priest and Keeper of the Sacred Buffalo Hat, founded the organization Guardians of Our Ancestors’ Legacy, “to stop the stripping of Endangered Species Act protection from grizzly bears, who are sacred relatives of the Cheyenne and other peoples.” With his nephew Rain Bear Stands Last, Shoulderblade “unified more than 200 tribal nations in The Grizzly: A Treaty of Cooperation, Cultural Revitalization and Restoration and inspired legal victories in 2018 and 2020 overturning the removal of federal protections.”

A report in 2020 revealed the pro-hunting view: Chad Day (president of the Tahltan Central Government, the administrative governing body of the Tahltan Nation, argued “that not all areas of [British Columbia] have conservation concerns about grizzlies, which can kill up to 40 ungulate calves each month, according to studies in Alaska and other parts of the United States.” Day was quoted as follows: “They are the apex predators in our country…They are extremely dangerous to not just other wildlife but to people and the conservation efforts of other (prey) species that we hold dear as Canadians, British Columbians and Indigenous people.” Others in the U.S. argue that grizzly bear populations have been threatened: “Grizzly bear mortalities have increased dramatically since roughly 2000, far in excess of anything that can be explained by changes in population size.”

In Sweden, animal rights groups also point to limits on the bear population. One such group, Svenska Rovdjursföreningen, explained on August 23rd that “the brown bear is classified as ‘near threatened’ according to the so-called ‘Red List.'” So a recently authorized “bear hunt is not compatible with the survival status of the species.” The group explains that “red listing is about assessing a species’ risk of extinction (population decline) and the assessment is made by experts at SLU, the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.” So the term “near threatened” means that a “species is not considered stable and viable, but also not so weak that there is a direct threat of extinction.” In any case, “there may be a risk of the status changing relatively quickly due to, for example, too heavy hunting pressure, or if the tribe is affected by some disease.”

The group argues that bear hunting is unethical: “Stressed by sharp dogs, the bears run for their lives, but quickly overheat due to their thick fur. Game must not be subjected to unnecessary suffering during hunting. Mother bears try to protect their cubs by getting them to sit in safety, for example in a tree, and then distract the hunters themselves. Shooting females with cubs is not allowed, but if they are separated, the females are sometimes shot by mistake, as the hunter does not know she has cubs. The yearlings cannot survive without their mother, but then they too must be shot.”

The Middle Class Expansion as a Species Threat

In authorizing bear hunts Swedish government agencies have argued that it reduces “the damage caused by bears to reindeer husbandry, and the belief that a reduced bear population would contribute to favourable psychosocial conditions for the human population in the counties where bears are present. A further aim is to reduce the bear population in relation to the management objectives on a county-by-county basis.” Here we see how deer commerce, technocratic objectives, and human psychosociology are deployed in defense of human species narcissism.

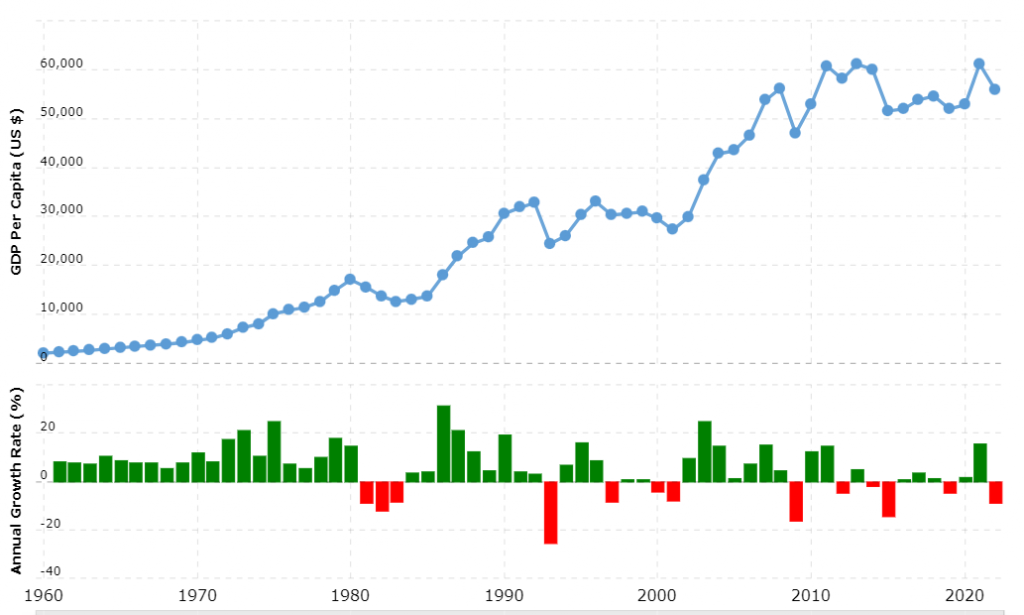

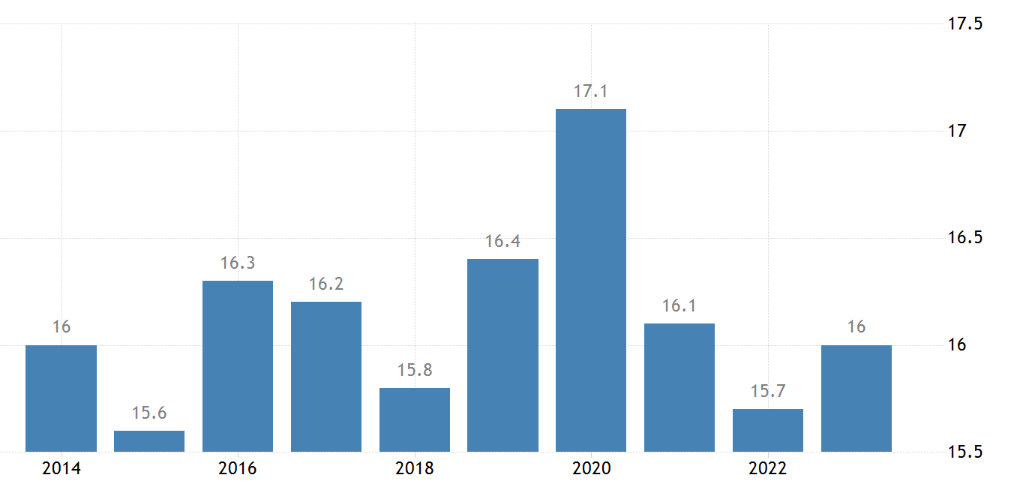

By means of hunting middle class lifestyle and conveniences are protected and advanced at the expense of other species. This practice constitutes species-narcissism. In 1979, the Norwegian philosopher Arnae Naess wrote an essay entitled, “Self-realization in Mixed Communities of Humans, Bears, Sheep, and Wolves,” in the journal Inquiry (Vol. 22). There Naess explained that “in the industrialized states the average material standard of living…has reached a fabulously high level, the highest in the history of mankind.” Yet, “at the same time the number of animals, especially mammals, subjected to suffering and a…restricted life-style in the richest countries has increased exponentially.” Figure 1 chronicles that growth in gross domestic product per person in Sweden over the last forty or so years. Figure 2 shows that this growth is still at the expense of a significant share of the population. Note that according to Statistics Sweden, the proportion of foreign born persons at risk of poverty in 2021 was 35.6%. So, non-migrant Swedes benefit more from the middle class bonanza.

Figure 1: GDP Per Capita in U.S. Dollars, 1960-2022 in Sweden

Source: Macrotrends, 2023, accessible at: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/SWE/sweden/gdp-per-capita#:~:text=Data%20are%20in%20current%20U.S.,a%2015.72%25%20increase%20from%202020.

Figure 2: The Rate of Persons at Risk of Poverty in Sweden

Source: Eurostat data on percent of persons in Sweden at risk of poverty as compiled by Trading Economics, 2023. Accessible at: https://tradingeconomics.com/sweden/at-risk-of-poverty-rate-eurostat-data.html#:~:text=Sweden%20%2D%20At%20Risk%20of%20Poverty%20rate%20was%2016.00%25%20in%20December,EUROSTAT%20on%20August%20of%202023.

The Geography of Human Species Killer Narcissism

The technocratic defense of bear hunts violates Naess’s argument that “there is a vast variety of ways of living together without destroying others’ potentials of realization.” In contrast to a diversity of species, we see “exclusivity” (very ironic given Sweden’s belief in its championing of “solidarity”). The bear hunt represents exclusivity. As Naess sees exclusivity in “the maximal realization of potentials of one life-form on the non-maximal realization of potentials of some other forms.” Yet, Naess brings thinks back to the class dynamic of human being’s life style: “Clearly a policy of restraining certain forms and life-styles in favour of others is called for–in favour of those with high levels of symbiosis, or more generally, good potentialities of existence.” Naess concluded that we must defend “the hunted against the hunters, the oppressed against the oppressors.”

At the national scale, Sweden scored in 49th place in a 2016 study of countries defined by their levels of empathy. In contrast, Ecuador was ranked first, Denmark fourth, and the U.S. seventh. In contrast, another study published in 2022 found Sweden was one of the least narcissistic countries in the world. Of course such studies depend on their measurement systems or indicators. For example, the study on narcissism appears itself to be defined by species narcissism: “Collective narcissism is a belief that one’s social group is exceptional and entitled to special treatment but not appreciated enough by others…It is typically studied in relation to one’s national group…, in which case it is termed ‘national collective narcissism,’ or more simply, ‘national narcissism.’ National narcissism goes beyond the nationalistic conviction that one’s nation is superior.” This study did not contain the words “animal,” “animals,” or even “species.” An academic study on narcissism which is itself narcissistic on the species front should give us pause.

In the U.S. state of Connecticut, various “bear attacks” have led to the use of guns to kill bears. On August 25, 2023, two hunters were injured in a recent bear hunt in Sweden. The bear hunt began on August 21st, when the killing of 622 bears was authorized throughout Sweden. Swedish TV and radio have interviewed human beings about their thoughts about killing bears. In contrast, bears can’t easily be interviewed as we don’t fully understand their language, they have no human voice, although there are studies of bear language. One argument is that bears must be attacked because they are aggressive against human beings in their territory.

In 1990, David J. Mattson summarized key issues related to the bear population in “Human Impacts on Bear Habitat Use,” in Bears: Their Biology and Management, Vol. 8, 1990, pp. 33–56. Mattson explained: “Human effects on bear habitat use are mediated through food biomass changes, bear tolerance of humans and their impacts, and human tolerance of bears. Large-scale changes in bear food biomass have been caused by conversion of wildlands and waterways to intensive human use, and by the introduction of exotic pathogens. Bears consume virtually all human foods that have been established in former wildlands, but bear use has been limited by access. Air pollution has also affected bear food biomass on a small scale and is likely to have major future impacts on bear habitat through climatic warming. Major changes in disturbance cycles and landscape mosaics wrought by humans have further altered temporal and spatial pulses of bear food production. These changes have brought short-term benefits in places, but have also added long-term stresses to most bear populations. Although bears tend to avoid humans, they will also use exotic and native foods in close proximity to humans. Subadult males and adult females are more often impelled to forage closer to humans because of their energetic predicament and because more secure sites are often preempted by adult males…. Elimination of human-habituated bears predictably reduces effective carrying capacity and is more likely to be a factor in preserving bear populations where humans are present in moderate-to-high densities. If humans desire to preserve viable bear populations, they will either have to accept increased risk of injury associated with preserving habituated animals, or continue to crop habituated bears while at the same time preserving large tracts of wildlands free from significant human intrusion.” Emphasis added.

The problem here is that the expansion of human beings’ use and appropriation of bear habitats is not called into question. For if this encroachment were reduced, then exposure to bears and risk of injury to bears would be reduced (all things being equal). The question of appropriation needs to be mediated by data on the growth or shrinkage of forests. A survey by Kathi Rowzie in October 2020 (before the latest cycle of forest fires) explains: “Since 1990, there has been a net loss of 440 million acres of forests globally, an area larger than the entire state of Alaska. A net change in forest area is the sum of all forest losses (deforestation) and all forest gains (forest expansion) in a given period. FAO defines deforestation as the conversion of forest to other land uses, regardless of whether it is human-induced. FAO specifically excludes from its definition areas where trees have been removed by harvesting or logging because the forest is expected to regenerate naturally or with the aid of sustainable forestry practices.” Yet “total forest area in the United States actually increased and forest area in Canada has remained stable since 1990…despite deforestation by urban development, fire, insects and other causes.” One of the main reasons is due in great part to “sustainable forest management practices implemented by the North American paper and forest products industry, the highest percentage of certified forests (nearly 50%) in the world, and laws and regulations aimed at protecting forest resources.” Global deforestation data shows relatively stable forest growth in both Sweden and the United States, but some countries like Brazil, Tanzania and Indonesia clearly decrease forest size. China, Russia and India have increased the size of their forests in recent years.

Bear Attacks are Minimal

Globally, there are 40 attacks on human beings every year according to data published by the World Animal Foundation. A study published by Giulia Bombieri and colleagues in Nature on June 12, 2019 found that while brown bear attacks on human beings were on the rise, with 664 brown bear attacks between 2000 and 2015 “across most of the range inhabited by the species: North America (n = 183), Europe (n = 291), and East (n = 190).” During these attacks, “half of the people were engaged in leisure activities and the main scenario was an encounter with a female with cubs,” with attacks increasing “significantly over time” and being “more frequent at high bear and low human population densities.” Furthermore, “there was no significant difference in the number of attacks between continents or between countries with different hunting practices.” Emphasis added.

Bombieri and colleagues published another study in BioScience in 2019 which explained that “public tolerance toward predators is fundamental in their conservation and is highly driven by people’s perception of the risk they may pose.” In addition, “although predator attacks on humans are rare, they create lasting media attention, and the way the media covers them might affect people’s risk perception.” Therefore, part of the “bear problem” may instead be a media problem.

Contrasting Geographies: When Sweden Makes Florida Look Like an Anarchist Utopia

Sweden has about 2,800 bears. In contrast, in 2017, there were 4,050 bears in the U.S. state of Florida alone. Sweden is 3.2 times larger than Florida, however. Sweden’s population was about 10.623 million persons in August 2023. In contrast, Florida’s population in 2023 was about 22.24 million or about double the size of Sweden’s population. How is it that Sweden which is larger and less populous than Florida, has far fewer bears? One potential basis for comparison is that “urban density in Florida tends to be higher than in Sweden due to the higher population growth rates and the concentration of urban areas, especially in cities like Miami” (according to a ChatGPT search conducted on August 27, 2023). Unlike Sweden, Florida did not hold a bear hunt this year.

Bear attacks on human beings in Florida appear to be very rare. In Sweden, we see that hunting bears provokes bear attacks on human beings. Last year CNN reported on “the 14th documented attack against a person causing moderate to serious injuries by Florida black bears since 1976,” when records were collected first by a monitoring group. Since 1902, there was been on one bear killing and two suspected deaths in Sweden, according to a report in The Telegraph (August 22, 2023).

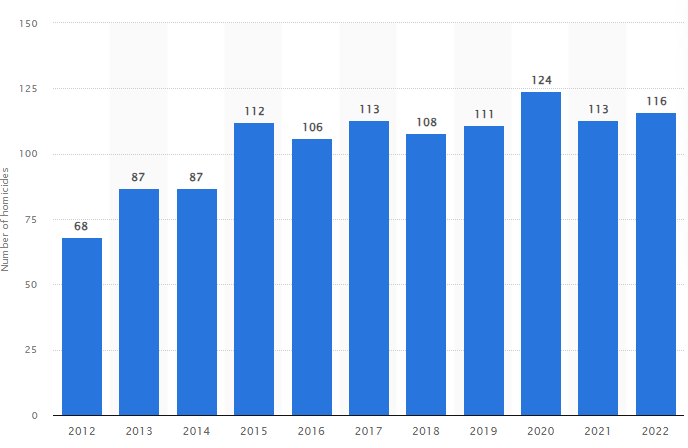

In Sweden, human beings are far more dangerous than bears in threatening human life. Here are some statistics. First, bears are less of a threat to family life, than human beings according to crime data: “According to estimates by the National Council for Crime Prevention (BRÅ), at least 7% of the Swedish population is exposed yearly to domestic violence, both men and women in roughly equal parts. However, women are much more likely to report recurring violence and to end up hospitalized.” Macrotrends provides some useful data on murder rates in Sweden. In 2012, there were .71 murders per 100,000 persons. By 2020, that increased dramatically to 1.20, decreasing to 1.08 in 2021. Figure 3 provides Statista-compiled data on the total number of homicides in Sweden from 2012 to 2022. As can be seen, the number of killings by human beings significantly dwarf the killings of human beings by bears (which seems to collectively total three in a period lasting more than 100 years). Capital punishment was last used in Sweden in 1910 and is now outlawed.

Figure 3: Homicides in Sweden

Source: “Number of homicides in Sweden from 2012 to 2022,” Statista, March 31, 2023. Accessible at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/533917/sweden-number-of-homicides/.

Hunting is based on the idea that killing one species will serve other species and humans well. Yet, Swedish institutions regularly authorize technology diffusion that threatens others outside of Sweden. The degrading of the moral value of the bear is not that different from the moral degrading of the non-Swede. In 2020, Diakonia noted that “Sweden’s seven largest banks” invested about five billion SEK in companies exporting weapons to countries violating human rights and “involved in armed conflicts.” Sweden also legalized weapons sales to Turkey even after it had recently slaughtered Syrians. Swedish weapons are also involved in the deadly conflict in Yemen. So the threats by bears are in consequential. The bear hunt defends what turns out to be a very selective species narcissism, defense of certain Swedes’ right to engage in violence. No one would seriously suggest culling Swedish arms exporters who threaten life in other countries.

Hunting of bears is linked to protection of other species: “Bears are known as the most dangerous predators in Sweden. Their existence in Sweden directly impacts the historic reindeer. As a result, the Swedish government has allowed hunters to hunt approximately 300 bears per year to curb their threat.” The hunting quota has been raised to protect these deer. A Google Search on August 27, 2023 found that the phrase “historical bears” (historiska björnar) led to only two hits. In contrast, “historical reindeer” (historiska renar) led to 1,200,000 hits. Bears have a kind of public relations problem in contrast to the reindeer. Naess says that for some sheep herders, “letting bears live is an interest” that involves “intrinsic values.” He also noted how economic interests have propelled hunting of bears in Norway as part of a self-reliance move attached to sheep production.

There are about 300,000 hunters in Sweden. In contrast, Florida with a population about double that of Sweden had 217,113 licensed hunters in 2021, or about 1% of the population. Using the previous data we see that about 2.8% of the Swedish population are hunters, i.e. about three times the share in Florida. Sweden has a very substantive hunting culture. One interesting development is the emergence of an extremist hunting culture in defiance of European Union transgressions against rural hunting culture. An article by Erica von Essen and colleagues published in The Journal of Rural Studies, “The radicalisation of rural resistance: How hunting counterpublics in the Nordic countries contribute to illegal hunting,” Volume 39, June 2015, Pages 199-209, argues the point as follows: “hunters in the Nordic countries have mobilised in opposition to the large carnivore management regime established largely through the EU Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC). Deliberately disruptive conduct including political activism, sit-ins, violent threats and boycotts of game management duties has increasingly been undertaken to challenge the authorities that represent conservation policy. In an extreme development, recalcitrant hunters have taken to breaking the law by killing protected wolves (Liberg et al., 2012) in defence of their livelihoods and lifestyles (Pyka et al., 2007).” So hunters have proactively organized to break the law in pursuit of their hunting aims. Likewise, a kind of violent reaction is directed to those in Sweden who oppose NATO and Swedish militarism.

Transformative Philosophy is Always Being Sacrificed to Power and Violence

An academic study published by Jon E. Swenson and colleagues, “Challenges of managing a European brown bear population; lessons from Sweden, 1943–2013,” in Wildlife Management in 2017 on managing brown bear populations in Sweden found that “many in Sweden seem to be skeptical to the idea of involving researchers in management.” The article explains the changing culture of bear hunting in the country: “Swedish public policy regarding the brown bear Ursus arctos has changed greatly through the centuries. Early on, the national policy was to exterminate the species and bounties were introduced in 1647 as a measure to help reach that objective. However, changing opinions among academics, hunters, and the public resulted in a paradigm shift at the end of the 1800s, leading to the abolishment of bounties in 1893 (Swenson et al. 56). Several other measures to protect bears, such as restrictions on where they could be killed and making any dead bear the property of the State, additionally contributed to the subsequent population increase (Swenson et al. 56).” Subsequently, “the management paradigm changed in 1943, when hunting seasons were introduced.” There are few philosophical parameters here as bear population increases are deemed problematic: “During 1991–2001, the management objective had been to continue the harvest rate as before to allow slow population growth and expansion. However, the population increased about 190% in 10 years or 11.2% annually, from ca 770 in 1991 to about 2220 (2006–2465) in the year 2000 (Kindberg and Swenson 20). Thus, the objective was not met, as the population grew much faster than anticipated.”

In contrast to banal technocratic discourse on bears and their “management,” Naess’s essay is one of the first references that pops up when one searches for “philosophy killing bears.” In his 1979 paper Naess argued that there was “a general abstract norm that the specific potentialities of living beings be fulfilled.” He went so far as to state that: “No being has a priority in principle in the realizing of its possibilities, but norms of increasing diversity or richness of potentialities put limits on the development of destructive life-styles.” In a refreshing style, far from the banality of most academic and media treatments, Naess asks basic questions: “The way animals are treated is determined not only economically and politically, but also through sets of general attitudes and beliefs, some of which are philosophically relevant. Academic philosophers have here a great variety of problems to choose from. ‘Do animals have rights?’ is one that has been at the forefront.”

Naess noted that the role of interests in relationship to animal destructions had to be considered, but that it was far more complex than a superficial understanding would have it: “The eating of sheep-flesh is not taken to be of high ‘level or importance of interest’ to bears in general. But to some bears it clearly is. Unfortunately we are not able to help a bear give up that interest. Sheep owners, on the other hand, have a strong economic interest in keeping their sheep alive. Even if the compensation they receive for the loss of a sheep is enough to buy two new sheep, and they thus make a profit out of the killing, sheep-owners have an interest in avoiding the killing.”

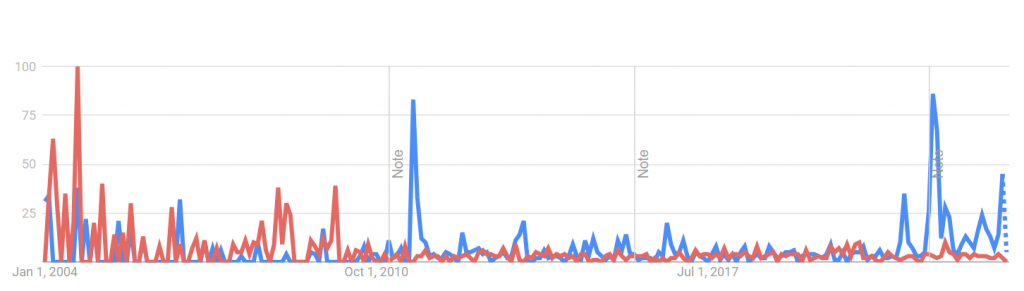

Decades ago Naess was involved in an historic battle with Jen Stoltenberg, then a shill for the oil companies, over Norway’s ecological future. This conflict was superbly explained by Peder Anker in his history of Norwegian ecological politics. In Figure 2 we see how Google searches reveal that Sweden has moved from a Naess-oriented culture to one dominated by Stoltenberg.

Figure 2: Google Trends Search of Arne Naess (red) versus Jens Stoltenberg (blue)

Source: Google Trends search by author, August 27, 2023. Accessible at: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=all&geo=SE&q=%22Jens%20Stoltenberg%22,%2Fm%2F039v0w&hl=en.

Of course Naess died in 2009 while Stoltenberg lives on. Nevertheless, Naess’s work is highly relevant for the current discussions of bear culling, yet in major news reports in Swedish mass media we get human interest stories on hunters. One rather popular one was of a young female hunter, something that fit in nicely with how Sweden and other countries periodically use gender symbolism to sell the country’s foreign policy violence to the public. One might also note how the discursive retrogression, or culture-moving-backwards, can be seen in other areas of Swedish political development, e.g. left parties’ actions on stopping or limiting arms exports and militarism as I noted elsewhere.

Given biodiversity requirements we must ask whether the carrying capacity of the human/ecosystem interface warrants the endless reproduction and expansion of human beings, particularly their intrusion on an animal’s natural habitats. While Malthusian restrictions on population growth are considered by some to be backwards, the normalization of bear killing to protect human population growth seems similarly backward. A deeper discussion in the media using Naess’s vantagepoint seems relevant, but rather difficult given the growing discursive regression.

The callous moral callus which defense Swedish arms exports can be seen in Swedish hunting. The technocracy again dominates with its pseudo-moralistic babble at the expense of life itself. The most dangerous species is the human being, particularly the violent, militaristic human. Hunting of animals is a kind of moral transgression in which the lesser destructive species is pursued by the far more violence one. This is a metaphor for collective stupidity. In this era of drones, artificial intelligence, stun guns, sleeping drugs and the like, it is impossible to argue that killing bears is necessary to protect reindeer. We can use some of the security budget which is actually reducing our security to protect the bears from the logic of the hunters. I have also explained elsewhere how species extinction and militarism are linked in Sweden.